If you want evidence that climate policy has become unhinged from science and quantification, becoming more like a religious cult, look no further than the recent Democratic presidential candidates' proposals to ban fracking immediately and nuclear power soon.

From Michael Cembalest at JP Morgan

I'm not a denier. Yes, carbon is a problem, warming is a problem, and a uniform carbon tax, vast expansion of nuclear energy, more renewables, lots of R&D on them, GMO foods, and geoenginnering are solutions. (If indeed warmer weather is an existential crisis, and if indeed $2 billion of soot in the upper atmosphere solves it, that should at least be on the table.) Actual, quantitative, scientific solutions. They don't atone for our carbon sins.

A ban on fracking and nuclear are not solutions, and will raise carbon emissions. The US is doing better on carbon reduction than other countries, because of fracking and natural gas. Unlike Germany, who has followed these policies, we cannot rely on Eastern European coal and Russian gas.

I am delighted to see that despite my fears of how extensive discretionary regulation will silence dissent, Mr Cembalest can still write such a note, with the JP Morgan imprimatur. We'll see how long such heresy survives more intense financial regulation and "stakeholder" control of corporate boards. "Eco-authoriarianism" and a "coercive green new deal" are already openly advocated, here for example.

Friday, September 13, 2019

Monday, September 9, 2019

More on low long-term interest rates

In an environment with stable inflation, the yield curve should typically be inverted.

Long term investors care about money when they retire, not next month. Most investors are long-term.

If inflation is steady, long-term bonds are a safer way to save money for the long run. If you roll over short-term bonds, then you do better when interest rates rise, and do worse when interest rates fall, adding risk to your eventual wealth. The long-term bond has more mark-to-market gains and losses, but you don't care about that. You care about the long term payout, which is less risky. (Throw out the statements and stop worrying.) So, in an environment with varying real rates and steady inflation, we expect long rates to be less than short rates, because short rates have to compensate investors for extra risk.

If, by contrast, inflation is volatile and real rates are steady, then long-term bonds are riskier. When inflation goes up, the short term rate will go up too, and preserve the real value of the investment, and vice versa. The long-term bond just suffers the cumulative inflation uncertainty. In that environment we expect a rising yield curve, to compensate long bond holders for the risk of inflation.

So, another possible reason for the emergence of a downward sloping yield curve is that the 1970s and early 1980s were a period of large inflation volatility. Now we are in a period of much less inflation volatility, so most interest rate variation is variation in real rates. Markets are figuring that out.

Most of the late 19th century had an inverted yield curve. UK perpetuities were the "safe asset," and short term lending was risky. It also lived under the gold standard which gave very long-run price stability.

(Yes, this argument is about portfolio variance, not beta, and assumes that the bond portfolio is a substantial part of the investor's wealth, or that inflation happens in bad times, at least over the investor's long horizon.)

***

This is a follow-up to low bond yields. That post has several good comments with links to the literature.

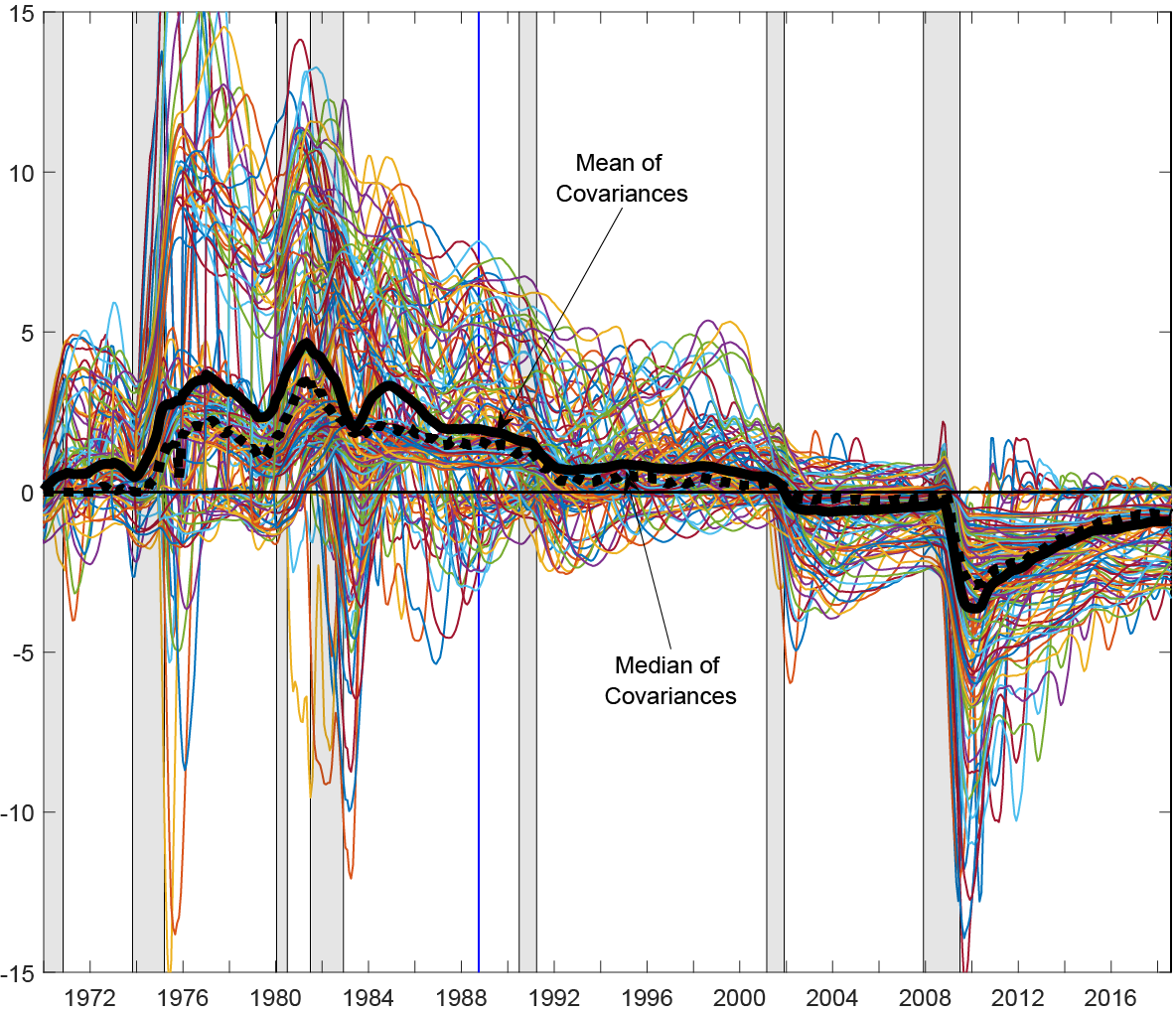

On that point, Uri Carl and Anthony Dierks send along this lovely graph from their note which makes the same point as my earlier blog post. The plot is different measures of the time-varying "covariance between Real Activity and Nominal Measures." The covariance changes sign, as I suspected.

Long term investors care about money when they retire, not next month. Most investors are long-term.

If inflation is steady, long-term bonds are a safer way to save money for the long run. If you roll over short-term bonds, then you do better when interest rates rise, and do worse when interest rates fall, adding risk to your eventual wealth. The long-term bond has more mark-to-market gains and losses, but you don't care about that. You care about the long term payout, which is less risky. (Throw out the statements and stop worrying.) So, in an environment with varying real rates and steady inflation, we expect long rates to be less than short rates, because short rates have to compensate investors for extra risk.

If, by contrast, inflation is volatile and real rates are steady, then long-term bonds are riskier. When inflation goes up, the short term rate will go up too, and preserve the real value of the investment, and vice versa. The long-term bond just suffers the cumulative inflation uncertainty. In that environment we expect a rising yield curve, to compensate long bond holders for the risk of inflation.

So, another possible reason for the emergence of a downward sloping yield curve is that the 1970s and early 1980s were a period of large inflation volatility. Now we are in a period of much less inflation volatility, so most interest rate variation is variation in real rates. Markets are figuring that out.

Most of the late 19th century had an inverted yield curve. UK perpetuities were the "safe asset," and short term lending was risky. It also lived under the gold standard which gave very long-run price stability.

(Yes, this argument is about portfolio variance, not beta, and assumes that the bond portfolio is a substantial part of the investor's wealth, or that inflation happens in bad times, at least over the investor's long horizon.)

***

This is a follow-up to low bond yields. That post has several good comments with links to the literature.

On that point, Uri Carl and Anthony Dierks send along this lovely graph from their note which makes the same point as my earlier blog post. The plot is different measures of the time-varying "covariance between Real Activity and Nominal Measures." The covariance changes sign, as I suspected.

Intellectual property and the trade deficit

"The IP Commission estimates that between $200 billion and $500 billion a year of intellectual property is stolen from the U.S." I found this interesting tidbit in The Atlantic interview of Kevin Hassett, ex CEA chair. (HT Marginal Revolution)

Well, suppose China were to pay up, and pay the $200 to $500 billion a year in royalty payments. Where would it get the money from? Hmm. It would have to sell us an additional $200 to $500 billion worth of exports, that's how. The trade deficit would have to increase.

China could sell us $200 to $500 billion a year of assets instead. Maybe we would like to hold lots of Chinese stocks, bonds, or government bonds rather than buy more boatloads of goods? But if we bought worthwhile Chinese assets, those are only claims on future Chinese profits. And the only use we have for lots and lots of Chinese currency profits is to... buy things in China and send them here. If we bought worthless assets, bonds that default, or stocks whose legal rights evaporate, then, well, we're back where we started.

Or maybe we don't want to license IP, we just think US owned firms operating in China could make an additional $200 to $500 billion per year profits operating in China without Chinese competition. And what do US owners want to do with $200 to $500 billion of Chinese profits per year? Go on a shopping trip, and put it on boats, sooner or later.

One way or another, the only way that China can properly pay for intellectual property, is to put more stuff on boats and send it to us. Paying for intellectual property must increase the trade deficit.

Being a free trader, I think this is great. The point of trade is to get the imports. The point of intellectual property is to force China to send us boatloads of stuff.

Somehow I don't think the Administration sees it that way. But you can't escape addition.

Well, suppose China were to pay up, and pay the $200 to $500 billion a year in royalty payments. Where would it get the money from? Hmm. It would have to sell us an additional $200 to $500 billion worth of exports, that's how. The trade deficit would have to increase.

China could sell us $200 to $500 billion a year of assets instead. Maybe we would like to hold lots of Chinese stocks, bonds, or government bonds rather than buy more boatloads of goods? But if we bought worthwhile Chinese assets, those are only claims on future Chinese profits. And the only use we have for lots and lots of Chinese currency profits is to... buy things in China and send them here. If we bought worthless assets, bonds that default, or stocks whose legal rights evaporate, then, well, we're back where we started.

Or maybe we don't want to license IP, we just think US owned firms operating in China could make an additional $200 to $500 billion per year profits operating in China without Chinese competition. And what do US owners want to do with $200 to $500 billion of Chinese profits per year? Go on a shopping trip, and put it on boats, sooner or later.

One way or another, the only way that China can properly pay for intellectual property, is to put more stuff on boats and send it to us. Paying for intellectual property must increase the trade deficit.

Being a free trader, I think this is great. The point of trade is to get the imports. The point of intellectual property is to force China to send us boatloads of stuff.

Somehow I don't think the Administration sees it that way. But you can't escape addition.

Sunday, September 8, 2019

Low bond yields

Why are interest rates so low?

Here is the 10 year bond yield, by itself and subtracting the previous year's inflation (CPI less food and energy). The 10 year yield has basically been on a downward trend since 1987. One should subtract expected 10 year future inflation, not past inflation, and you can see the extra volatility that past inflation induces. But you can also see that real yields have fallen with the same pattern.

There is lots of discussion. A falling marginal product of capital, due to falling innovation, less need for new capital, a "savings glut," and so forth are common ideas. The use of government bonds in finance, the money-like nature of government debt among other institutional investors and liquidity stories are strong too. And most of the press is consumed with QE and central bank purchases holding down long term rates. I hope the steadiness of the trend cures that promptly.

Along the way in another project, though, I made the following graph:

The blue line is 10 times the growth rate of nondurable + services per capita (quarterly data, growth from a year ago). The red line is the negative of an approximate measure of the real return on 10 year government bonds. I took 10 x (yield - yield a year ago), and subtracted off the CPI.

Look at the last recession. Consumption fell like a rock, while the real return on long-term bonds was great. That real return came from a double whammy: long term bonds had great nominal returns as interest rates fell, and there was a big decline in inflation. No shock, there is a "flight to quality" in recessions, along with a sharp decline in nominal rates. From a foreign perspective, the rise in the dollar added to the return of long-term bonds. The graph suggests this is a regular pattern going back to the almost-recession of 1987. In every recession, consumption falls, interest rates fall, inflation falls, so the real ex post return on government bonds rises.

Government bonds are negative beta securities. At least measured by consumption or recession betas. Negative beta securities should have low expected returns. They should be less even than real risk free rates. I haven't seen that simple thought anywhere in the discussion of low long-term interest rates.

Making the graph, I noticed it was not always thus. 1975, 1980, and 1982 have precisely the opposite sign. These were stagflations, times when bad economic times coincided with higher inflation and higher interest rates. Likewise, countries such as Argentina which go through periodic currency crises, devaluations, and inflations, flights to the dollar, all associated with bad economic times, should have the opposite sign. There is a hint that 1970 was of the current variety.

One could easily make a story for the sign flip, involving recessions caused by monetary policy and attempts to control inflation, vs. recessions involving financial problems in which people run to, rather than from, money in the recession.

In any case, the period of high yields was associated with government bonds that do worse in recessions, and the period of low yields is associated with government bonds that do better in recessions and have a negative beta. I haven't really seen that point made, though I am not fully up on the literature on time-varying betas in bond markets.

In any case, if we want to understand risk premiums in bond markets, this sort of simple macro story might be a good starting point before layering on institutional complexities.

Here is the 10 year bond yield, by itself and subtracting the previous year's inflation (CPI less food and energy). The 10 year yield has basically been on a downward trend since 1987. One should subtract expected 10 year future inflation, not past inflation, and you can see the extra volatility that past inflation induces. But you can also see that real yields have fallen with the same pattern.

There is lots of discussion. A falling marginal product of capital, due to falling innovation, less need for new capital, a "savings glut," and so forth are common ideas. The use of government bonds in finance, the money-like nature of government debt among other institutional investors and liquidity stories are strong too. And most of the press is consumed with QE and central bank purchases holding down long term rates. I hope the steadiness of the trend cures that promptly.

Along the way in another project, though, I made the following graph:

The blue line is 10 times the growth rate of nondurable + services per capita (quarterly data, growth from a year ago). The red line is the negative of an approximate measure of the real return on 10 year government bonds. I took 10 x (yield - yield a year ago), and subtracted off the CPI.

Look at the last recession. Consumption fell like a rock, while the real return on long-term bonds was great. That real return came from a double whammy: long term bonds had great nominal returns as interest rates fell, and there was a big decline in inflation. No shock, there is a "flight to quality" in recessions, along with a sharp decline in nominal rates. From a foreign perspective, the rise in the dollar added to the return of long-term bonds. The graph suggests this is a regular pattern going back to the almost-recession of 1987. In every recession, consumption falls, interest rates fall, inflation falls, so the real ex post return on government bonds rises.

Government bonds are negative beta securities. At least measured by consumption or recession betas. Negative beta securities should have low expected returns. They should be less even than real risk free rates. I haven't seen that simple thought anywhere in the discussion of low long-term interest rates.

Making the graph, I noticed it was not always thus. 1975, 1980, and 1982 have precisely the opposite sign. These were stagflations, times when bad economic times coincided with higher inflation and higher interest rates. Likewise, countries such as Argentina which go through periodic currency crises, devaluations, and inflations, flights to the dollar, all associated with bad economic times, should have the opposite sign. There is a hint that 1970 was of the current variety.

One could easily make a story for the sign flip, involving recessions caused by monetary policy and attempts to control inflation, vs. recessions involving financial problems in which people run to, rather than from, money in the recession.

In any case, the period of high yields was associated with government bonds that do worse in recessions, and the period of low yields is associated with government bonds that do better in recessions and have a negative beta. I haven't really seen that point made, though I am not fully up on the literature on time-varying betas in bond markets.

In any case, if we want to understand risk premiums in bond markets, this sort of simple macro story might be a good starting point before layering on institutional complexities.