On May 6 the annual Hoover monetary policy conference returned. It was great. In particular, the opening panels by Rich Clarida, Larry Summers, and John Taylor, and the final panel with Jim Bullard, Randy Quarles, and Christopher Waller were eloquent and insightful. Alas, the videos and transcripts aren't quite ready so you have to wait for all that. There will also be a conference volume putting it all together.

In the meantime, I wrote a paper for my short talk; and thanks to the Hoover team I also have a transcription of the talk. The paper is "Inflation Past, Present and Future: Fiscal Shocks, Fed Response, and Fiscal Limits." It pulls together ideas from a bunch of recent blog posts, other essays, bits and pieces of Fiscal Theory of the Price level. Sorry for the repetition, but repackaging and simplifying ideas is important. Here's the talk version, shorter but with less nuance:

Inflation Past, Present and Future: Fiscal Shocks, Fed Response, and Fiscal Limits

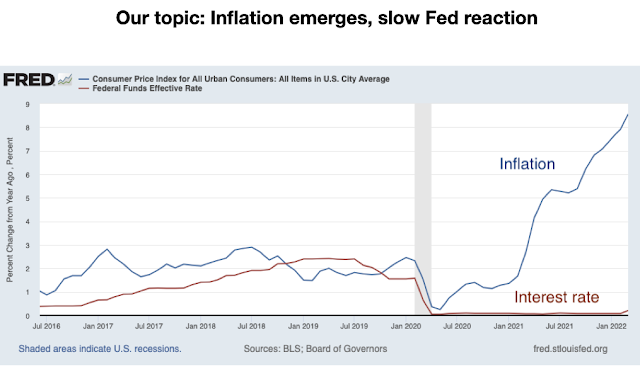

Here we are. Inflation has emerged, and the Fed is reacting rather slowly.

Why? Where did inflation come from, is question number one, and Charlie Plosser gave away the answer in his nice preface to this session: The government basically did a fiscal helicopter drop, five to six trillion dollars of money sent in a particularly powerful way. They sent people checks, half of it new reserves, half of it borrowed. It's a fiscal helicopter drop. Imagine that this had been simply $6 trillion of open market operations. Well, as Larry just told us, $6 trillion more $10 bills and $6 trillion fewer $100 bills won’t make much difference. If there had been no deficit, it certainly wouldn't have had such a huge effect.

The impulse was not the fault of interest rate policy either. Interest rates have just been flat. One can blame the Fed for contributing to the great helicopter drop, but not for a big interest rate shock.

So that's the inflationary impulse, but where is inflation going now? Now, attention turns to the Fed. Interest rates stayed flat while inflation got going from the fiscal shock, as you see in the first graph.

So the next question is, does this slow response; this period of nominal interest rates far below inflation, constitute additional monetary stimulus, which creates additional inflation on its own? Or are we simply waiting for the fiscal (or supply, if you must) shock to blow over?

The Fed is certainly behind the curve by historical standards. In this graph, the arrows point out every tightening since 1960. In every single one, the Fed raised interest rates roughly one for one or more with current inflation. Even the dreaded 1970s, the Fed never waited an entire year before doing anything at all.

Why did the Fed take so long to move now? There are many answers to this question, and I won't go deep into it. One of the features was likely forward guidance, which the previous panel alluded to. The Fed kept rates interest rates low because the Fed said it would keep interest rates low. There was this elaborate formal new strategy that said we're going to keep interest rates low. That strategy was, I think, a beautiful Maginot Line crafted against deflation but, as with the original, it forgot: what if the Germans come through the Ardennes instead? We discovered a halfway point between Larry and John Taylor. The problem of forward guidance is, does anyone believe the Fed will do it ex post? (Time consistency.) Critics like me who said no I think were proved wrong. The Fed held itself ex post to a good deal of what it had promised. Unfortunately, it promised something that was inappropriate in the circumstances, which is the whole point and conundrum of forward guidance. And what John would say is, well the Fed should have had promises that include, if a serious inflation breaks out, inflation, then we'll do something else.

The Fed in general does far too much “here is what we think will happen so here is what we are going to do,” and far too little contingency planning in case things don’t work out the way it projects. Which, we have just learned, can happen in large measure and with dramatic speed. Military planners know this. They red-team their projections, obsess over unlikely contingencies, and follow failures with detailed self-critical investigation. The Fed should also.

But like the shock, the year of inaction is in the past. The relevant question is where do we go in the future? That brings us back to the question: Is staying put so long itself additional stimulus, which will cause inflation? Or, assuming the fiscal shock is over and until the next shock comes along, will inflation go away on its own?

I've graphed here the Fed’s projections from the March 15 meeting for unemployment, federal funds rate and inflation. The Federal Reserve believes that inflation will go away all on its own without a period of high real interest rates. That, I think, is the central premise that most of our commentators disagree with. To them, a period of substantially low or negative real interest rates will accelerate inflation. They would say, these projections are nuts. But are they indeed nuts?

The markets, by the way, seem to agree with the Fed. Until the Fed started saying it's going to move, markets also seemed to think inflation would go away all on its own.

Well, one thing John emphasizes is to write down models. So I wrote down a model, so simple it can show up in the bottom of a slide. It says that output is lower when the real interest rate is higher, and a Phillips curve in which inflation depends on the output gap. Crucially, this model uses adaptive expectations in the Phillips and IS curves, as shown by the arrows.

Then I asked the question, let us start at last year's inflation, where the Fed projections start; assume the shocks are over, but we inherit this inflation. What happens if the Fed follows the blue line, the federal funds rate? The initial inflation is given. The blue line is given. From the model, I calculate where inflation and unemployment go from there. The dashed lines are the Fed’s projections.

I think this graph encapsulates the view the Fed is way behind the curve; that low interest rates below inflation constitute additional stimulus. Inflation spirals off, at least until it gives in, raises rates sharply and causes a recession, as Larry Summers warns. That looks pretty awful. And it looks like the Fed is completely wrong in its forecasts of what will happen if it follows this fund rate path.

But what if expectations are rational? Here's a little modification of the model with the arrows pointing to the changes. What if, the real interest rate and the Phillips curve are centered at expected future inflation rather than lagged inflation? Same simulation: Put in the federal funds rate path, anchor inflation at last year's inflation. Turn off all shocks. What happens? I obtain almost exactly what the Federal Reserve is projecting.

Intuitively, the rational expectations Phillips curve looks at inflation relative to future inflation. Unemployment is low, as it is today, when inflation is high relative to future inflation. Inflation high relative to future inflation means that inflation is declining. And that's exactly what this projection says. Rational expectations means you solve models from future to present. If people thought inflation was really going to be high in the future, inflation would already be high today. The fact that it was only five percent tells us that it's going to decline and go away.

To be clear I don't think the Fed thinks this way procedurally. They have a gut instinct about inflation dynamics, informed by lots of VAR forecasts and model simulations. But this theory gives a pretty good as-if description, a slightly more micro founded model that makes sense of those intuitive beliefs.

So the Federal Reserve's projections are not nuts! Inflation might just go away on its own! There is a model that describes the projections. And this is a perfectly standard model: it’s the new-Keynesian model that has been in the equations if not the prose of every academic and central bank research paper for 30 years. So, it is not completely nuts. Our job is to think about these two models and think about which one is right about the world.

To put the question in another way, let’s find what interest rate it takes to produce the Fed's inflation projection. What should the Fed be doing? With adaptive expectations, to make inflation fade away as the Fed thinks will happen, we need the interest rate to be nine percent. Right now. Why? Because you need a high real interest rate measured relative to lagged inflation in order to bring that inflation down. And we're way, way off the curve. I think this calculation encapsulates a lot of the Taylor rule view.

But what if inflation expectations are rational? Again I find what interest rate path, it takes to produce the Fed’s inflation path, Here, the Fed is a bit ahead of the curve.

A quick summary: The Fed’s projections are consistent with a standard New Keynesian model. This is not a nutty model. It's been around since 1990. It's the basis of essentially all academic macroeconomic theory. It may be wrong or right. The point of models is to help us understand what ingredients get to different views, and thereby also use evidence from other episodes to guide this one. I'm not advocating for against it. I'm just saying this is what we need to talk about.

Here are the core questions.

- How forward looking are expectations in the bond market, in the economy, and in the Phillips curve? Do people think about expected inflation, about what's going to happen next year? Or do they mechanically take whatever inflation happened last year?

In my view, the right answer is probably halfway in between. In the long run, people catch on. Why don't we see the huge spiral? Because once we get to spiraling inflation, people catch on and get more rational in their expectations. In the short run, with a new event, there is likely some adaptive dyanmics. So don't count on either one being perfectly right. But don't count on either one being incredibly reliable either.

Another, more uncomfortable way of putting the question,

- Is the economy stable or unstable with an interest rate that reacts less than one for one to past inflation?

The Fed’s projections say, stable. If we just leave interest rates alone, eventually, inflation will settle down. There may be a lot of short-run dynamics on the way, which these models don’t capture. But it settles down in the end. This answers Larry's last question. It's not necessarily a mistake. This is a model of the world in which nominal things do control nominal things, and the nominal interest rate eventually drags inflation along with it. A k percent interest rate rule is possible. Not necessarily optimal, but possible.

Third, there is an important quantitative question.

- Are prices as flexible and the Phillips curve as steep as the Feds projections imply?

The Fed’s projections have inflation coming down very quickly. Implicitly, prices are very flexible. Maybe not.

You may still think the Fed’s view is nutty, but there is now some important evidence on the table. That experience may have shifted the Fed’s view of inflation dynamics. The model of spiraling inflation and deflation also predicts that when interest rates are stuck at zero for 10 or 20 years, inflation or deflation will spiral away. And inflation didn't do that. The Fed funds rate was stuck at zero in the US for nearly 10 years. Inflation just batted around with a stuck interest rate. In Europe, inflation was stable with a stuck interest rate for a longer period. And in Japan, inflation was stable with a stuck interest rate for 25 years. The deflation spiral never broke out. Japan lived 25 years of the Friedman optimum quantity of money. This experience may be is something that the Fed is digesting in its verbal way, and that is what the rational expectations model says. So it's not as nuts.

Next, let’s think about how inflation is going to proceed in the future. In the Fed’s projections inflation comes down very quickly. To match that I had to take a price stickiness parameter of 0.5. That means a very steep Phillips curve. One percent output gap means one percent inflation. Most people think of the Phillips curve as having been quite flat. In the 2010s, unemployment moved a lot with little change in inflation. Today inflation is moving a lot with little change in unemployment. What is the real amount of price stickiness? Or is the whole Phillips curve a mess?

To get at this, and other issues, here is the response to a fiscal shock in the full equations of the standard new-Keynesian model. I add long-term debt, and I perform slightly unusual simulations: I ask how the model responds to a fiscal shock with no change in interest rate, and I ask how it responds to interest rate changes with no change in fiscal policy.

This is now a full shock simulation: Rather than take initial inflation as given, I hit the model with a 1% fiscal shock, no change in interest rate, and derive the entire inflation path. What happens? Inflation rises, and then does go away on its own.

This is the stanford three equation model. So it really is not nutty that inflation would go away on its own.

But it takes years for inflation to go away. I cut the price stickiness parameter in half, but I still have a pretty steep Phillips curve. Using the full model adds persistence. So the Fed may also be wrong in thinking that inflation will disappear on its own quite as quickly, even if the fiscal shock has ended (as it has in the simulation) and even given its view that inflation is stable in the long run.

A one-time fiscal shock can lead to drawn out inflation, not a one-time price-level jump. We may have a ways to go. In this model the 8% inflation we have just seen is only 40% of the eventual price-level rise.

Now, what can the Fed do about inflation? Suppose the Fed does start raising interest rates aggressively? Here I feed the model an AR(1) interest rate, with no fiscal policy shock, to evaluate the independent effect of monetary policy. Many models implicitly specify that when the Fed raises interest rates sthere's a big increase in surpluses. We're just going to leave fiscal policy alone and see what happens in what is the apparently Fed’s model, if the Fed raises interest rates.

The interest rate rise does lowers inflation, but only in the short run. There's a form of Tom Sargent’s “unpleasant arithmetic”at work. Lowering inflation today raises inflation in the future. We had a fiscal shock. That has to come out of the pockets of bondholders, by inflating away bonds. The Fed can choose to inflate that away now or inflate it away in the future. But the Fed cannot get rid of the fact that there has been a fiscal shock which inflates away debt. So it has a limited power. It can smooth inflation but cannot completely get rid of inflation.

What if there is a 1% fiscal shock, but the Fed responds with something like a Taylor rule? We basically add the last two figures. We get lower inflation in the short run, but much more persistent inflation in the long run. Smoothing inflation is a great thing in this model. It reduces output volatility. (Output is related to inflation relative to future inflation, so has almost no movement here.)

We have one more reason for a Taylor rule: It does not give us stability, as it does in adaptive expectations models, it does not give us determinacy as it does in new-Keynesian models. It gives us quiet, the absence of volatility, which is perhaps the best of all.

Now let’s think about the further future. This is the CBO’s debt and deficit graph to remind you of our fiscal situation. We don't have just a one-time $6 trillion helicopter drop, we have an ongoing fiscal problem. The CBO’s projection is debt if nothing bad happens. But every 10 years we have a shock, and the debt goes up again like a cliff.My little black line there is a guess of what happens with occasional shocks. In sum, we have five percent of GDP structural deficits, once per decade stimulus/bailouts, and here comes Social Security and Medicare.

If there isn't more bad fiscal news, there are fiscal constraints of monetary policy. In 1980, there was only 25% debt to GDP ratio. Now it’s 100% and rising. We need coordinated fiscal and monetary policy to get out of a serious inflation. But the fiscal constraints on monetary policy are going to be four times harder this time.

How? First, there are interest costs on the debt. Suppose the Fed raises interest rates to five percent. We've been talking about eight, nine, ten percent, so five percent isn't that much. But today five percent interest rate is five percent of GDP debt costs, a trillion bucks. If the Fed wants to raise real interest rates 5% to fight inflation, we need a fiscal contraction of a trillion dollars a year to pay those debt costs, or else raising interest rates does not stop the inflation.

Second, once inflation gets baked in to bond prices, then if we disinflate, the government has to pay bondholders a big windfall, by repaying debt in more valuable dollars. Ten percent disinflation and 100% debt to GDP ratio means a ten percent of GDP present from taxpayers to bondholders. If we don't pay that, the monetary tightening will fail.

And we've seen that failure in Latin America. Countries get into fiscal problems, they have inflation, they raise interest rates, that just raises debt costs, and the inflation spirals on up.

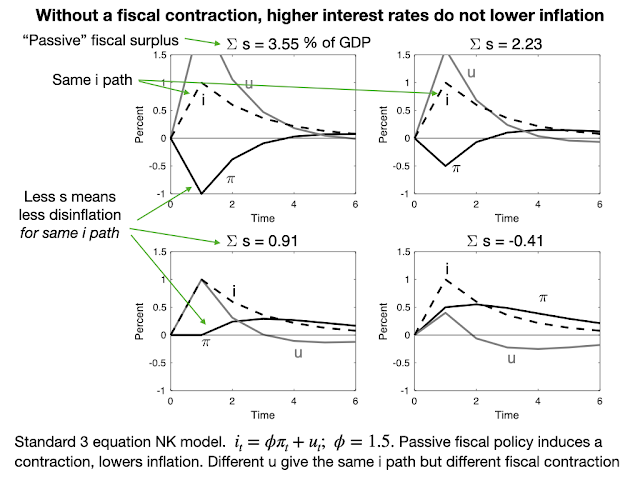

Here is a simulation of that effect. Here I took a totally standard New Keynesian model -- none of this fiscal theory of the price level stuff. I ask what happens if the Fed raises interest rates, following the dashed line? In the top-left graph, you see that interest rate go up and inflation goes down. The rate rise lowers inflation. But that higher nominal interest rate with lower inflation means higher debt service costs and a present to bondholders. New Keynesian models say that Congress and Administration “passively” provide whatever fiscal backing is needed, but how much is it? The title calculates: This disinflation requires 3.5% of GDP fiscal surpluses.

What if Congress says, to the Fed: “You're out of your minds. We're not doing that.” Well, then it can’t happen.

In the second simulation, I follow the same interest rate path, but in the New Keynesian model, by changing the time-series pattern of the monetary policy shock, you can get the same observed interest rate with less needed fiscal policy. So here, I have the same interest rate path but only 2.3% of GDP fiscal surpluses coming out of Congress. But you get less disinflation out of it. In the bottom bottom right, Congress only provides 0.91% of GDP fiscal surpluses. The interest rate goes up, but now inflation doesn't move at all. There are still surpluses, because we still have to pay the higher real interest costs. In the bottom right case, higher interest rates raise inflation. Why? Because in this case, we have deficits.

Without without coordinated fiscal policy tightening, raising interest rates will not lower inflation. Even in the completely stock New Keynesian model.

What about 1980? 1980 was not just monetary policy. 1980 was a joint monetary, fiscal, and micro economic deregulatory reform. It set off a boom in growth that set off a boom in tax revenues. It exactly was a fiscal reform and tightening. I graph here the primary surplus following 1980. Most of the “Reagan deficits” were just higher interest costs on a very large debt. By the 1990s you can see fiscal surpluses were surging. It took a while, but there was a fiscal and deregulatory reform (1982, 1986) that went with the monetary reform. Whether by those reforms or just by luck, growth took off, and paid off a lot of that debt.

You can see this in the debt to GDP ratio even, which includes interest costs on the debt. By the 1990s, those reforms were paying down the debt.

Suppose that you bought bonds at a 15 percent yield in 1980. By the late 1990s, you got those back at four to five percent inflation. You got a ten percent per year rate of real rate of return, courtesy of taxpayers. Much debt was rolled over at higher rates, courtesy of taxpayers. The graph also warns us that bond yields never have been very good at forecasting inflation.

The joint fiscal and monetary policy was absent in many Latin American countries. They raise interest rates, the deficits don't get cured, and the whole thing falls apart. That could have happened in the US as well.

Last, I offer some good news. We're forgetting a lot of the economics of the 1970s and 1980s. We can have painless disinflations. We keep talking as if we have to redo 1980, and endure a horrible recession. There is a way out. And the way out is to coordinate the fiscal, monetary, and micro economic reform to a durable new regime, move that expected inflation term in the Phillips curve, by having people convinced that it really is going down. Then we get a miraculous disinflation. It can happen. It does happen.

I offer three examples. First, remember the inflation targeting reforms of the early 1990s. This one is New Zealand. The GST notation signals rise in goods and service taxes. There was also a suite of microeconomic deregulatory reforms. The inflation target was a joint fiscal, micro economic, and monetary reform. Inflation dropped like a stone with no recession at all. The central bank never needed to use its independence to replay US 1980. It turns out that is not the point of inflation targets!

Canada did the same thing in the early 1990s. The inflation target was not just, “Dear Reserve Bank of Canada, plese be tougher.” It was also a commitment by the Treasury, “we're going to raise taxes if necessary to pay off our debts at this and only this value of inflation.” It also included micro economic reforms. Inflation melted away, like snow by about mid-July in Canada.

And of course, as Tom Sargent told us, remember the famous ends of hyperinflations. Inflation stopped on a dime, even with lower interest rates, even with printing more money, even with more short-term deficits, because countries solved the structural fiscal problem.

If we get to the point that we need to disinflation, remember that all successful disinflations, including the US in 1980, has been joint monetary, fiscal, and micro economic. But they had to reform to credible, durable, time-consistent regimes. You can't forward-guidance your way out of inflation. You can’t just give more speeches about “anchoring.”

Remember “WIN” (Whip Inflation Now) buttons? They may be coming back as we replay the 1970s. They were, of course the ultimate attempt at forward guidance or expectations management that didn't work. You need a durable change of regime so that people understand the underlying fiscal problem is solved.

But back to doom and gloom. We will have a new fiscal shock, something bad is going to happen sooner or later, and we have little fiscal space. If (when?) China invades Taiwan, we're going to have a huge financial and economic shock, along with a nasty war. The government is going to try to to borrow or print another $5-$10 trillion to bail out, stimulate, insure, and fight a war. On top of, say 150% debt to GDP and unreformed entitlements. It will be very interesting to see what happens then.

In my reading, we have crossed the Rubicon. We have found the point that people didn't want our debt anymore, started to spend it, and caused inflation. Are we now at the fiscal limit where we can't do a big deficit-financed stimulus again? Or do people, can people, think that future deficits will be repaid by even further future surpluses, and they will happily lend those trillions without inflation?

So here's the unknown theoretical question number two.

- Is fiscal inflation a stock or a flow phenomenon? Deficits vs. GDP gap, or debt vs. expected repayment?

I think Larry Summers’s vision, beautifully articulated, is a flow limit. The deficit multiplied by 1.5 should not be bigger than the GDP gap. If it is, you get inflation. So long as the flow of deficits is below that, don't worry about increasing the debt; we can always pay it off sooner or later.

The view I'm putting up here is a stock view, a present value view. Inflation is fundamentally when we have too much debt relative to people’s expectations that the government can pay it back in the future. Then even small deficits, or changes in those expectations, can cause us fiscal problems.

We have good and fundamental questions. Let’s debate the answers.

Excuse me for querying this, it's very interesting, but how do you account for countries with low government debt yet a similar inflation rate to more highly indebted countries like the US?

ReplyDelete"Inflation is fundamentally when we have too much debt relative to people’s expectations that the government can pay it back in the future."

I agree, I'd be interested in reading John's answer to this question. Some emerging market economies are experiencing high inflation and did not engange in any fiscal expansion. So how general it the FTPL to explain inflation everywhere?

DeleteSome countries don't go through the rigamorole of government debt - they print the currency directly.

DeleteSome service based countries (vacation, tourist spots) rely primarily on imports for goods and so are importing a lot of inflation.

Some countries maintain currency pegs - again importing inflation.

Some countries are regularly engaged in warfare (destruction of productive enterprise). In that case in really doesn't matter how a government is financing it's troops (debt, printed money, other).

This is exactly what I was thinking when reading this. The reality is: supply shocks matter (supply chain disruptions + commodities), especially in countries with volatile inflation expectations.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteYou are presuming that a government must sell bonds in the first place.

Deletehttps://musingsandrumblings.blogspot.com/2019/09/the-case-for-equity-sold-by-u.html

What good does a government bondholder produce that "entitles" that person to ever receive a positive real return on investment?

See the 14th amendment to the Constitution for your answer.

"This reader would ask you, If bond investors took their money off the table, how would government be able to afford to pay for the programs, the pensions (Social Security, Medicare/Medicaid, Federal Farm Credit, &c.) that Congress has legislated?"

Are you really this clueless? Social Security has a dedicated source of tax revenue (FICA taxes). Does this?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FDEFX

The only reason you think a government "needs" to sell bonds is because you also think a government "needs" to wage war and destroy productive enterprise.

DeleteYou and Putin would make a good pair.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Delete"Your Government equity doesn't comes close to that."

DeleteMy government equity comes close enough in that as long as you are working a job and have an associated tax liability, you will see a benefit.

It's all about the incentives.

"The government's current revenues are not sufficient to cover its current expenditures. (transfer payments to persons + wages to gov't employees + gov't capital asset acquisitions + interest on debt, &c.) "

And the same can be said for any company that sells equity shares (revenues not sufficient to cover expenditures).

"Eighty percent of federal government debt is held domestically."

Sure, if you count the $6 trillion (out of $30 Trillion total) = 20% owned by Federal Reserve banks.

Finally, you didn't answer the question:

What good does a government bondholder produce that "entitles" that person to ever receive a positive real return on investment?

If the Fed doesn't believe that bondholders are entitled to a positive real rate of return.

DeleteIf the "bond market vigilantes" don't believe that bondholders are entitled to a positive real rate of return.

If Treasury & Congress doesn't believe that bondholders are entitled to a positive real rate of return.

If foreign investors don't believe that bondholders are ventilated to a positive real rate of return.

Then you are you to argue with all of them?

"FICA contributions by employees and employers won't cover future obligations for social security benefits and transfers by the 2nd half of the current decade, unless FICA contribution rates rise significantly."

DeletePrimarily because of this:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/POPTHM

US population growth fell to near zero in May of 2021. Government insurance programs don't work that well with declining populations.

Interesting models and opinions. How does the fact that the dollar seems stronger fit into this?

ReplyDeleteHi John, Will hoover publish the video from this at some point? I've been waiting for weeks to watch these central bankers eat the crow they order up last year. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteBook and videos on the way.

DeleteWhat microeconomic regulatory reforms do you have in mind? Why don't the reforms from the past fix the current problems? New technologies? And what about the consistent 13% rate of increase of spending over the past year and a half, almost all of it due to increases in the rate of growth of the money supply (i.e., V rog is about zero)? Uncle Milty would like to know.

ReplyDeleteThe Reagan fiscal / monetary reforms that drove tax receipts higher weren't even that. They were primarily driven by this:

ReplyDeletehttps://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EMRATIO

Employment to population ratio (1978) = 58.8

Employment to population ratio (1989) = 63

I am still puzzled by how your theory explains the 2010s. Obama run huge deficits, both in the current cash flow sense and in a present value sense (unfunded ObamaCare liabilities). He was indifferent to reducing deficits or paying for spending. He wanted to raise taxes, but narrowly and not enough to fund the expansion of government. Even so, inflation was chronically low during the Obama years. And even when Trump taxes, inflation stayed low. There were massive deficits in 2020 from the CARES Act, but inflation stayed low. I am not seeing any fiscal theory of inflation.

ReplyDeleteMy main question is why are not fiscal flows taken into account. We know that if we have a small country, currency fluctuations caused by large capital inflows/outflows can impact measured inflation/deflation (largely through imports becoming cheaper/more expensive due to the resulting currency fluctuations). Starting in the 80s, we have had both Japan and then China (and others of course, but those were the big dogs) invest large amounts of capital with the expressed goal of keeping the dollar strong. Strong currency is generally disinflationary. I would think this should be incorporated into the modals for why things were different post 1980.

ReplyDeleteHello - and thank you for this thoughtful piece.

ReplyDeleteThe time series leaves out the post-WWII and Korean War inflationary periods, beginning just after them. These seem the best comparison for post-Covid inflation - is there a reason you left them out? Does including them change your conclusions?

Excellent article with much to think about, presented very clearly. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteHowever:

"A quick summary: The Fed’s projections are consistent with a standard New Keynesian model. This is not a nutty model. It's been around since 1990. It's the basis of essentially all academic macroeconomic theory. It may be wrong or right."

This may be the most damning statement against modern macro I've yet seen from an economist.

A close second is that model inflation can vary all over the place with just small assumption changes. The predictive power here seems awfully low, as it has been in the past.

Thanks, this was excellent!

ReplyDeleteFor the less academic of us — would you be able to define the terms (x / sigma / i / r / K / pi) in the simple models? Or is there a link that explains these?

x is output, i is interest rate, pi is inflation. sigma, r, and kappa are parameters. r is the long run real rate of interest. All variables are deviations from steady state, so mean zero. Details in "fiscal theory of the price level" on my webpage.

DeleteI lived in New Zealand in the late 1980's and early 1990's and I can tell you that there were two recessions during that period of moderating inflation, one triggered by the 1987 NZ sharemarket crash, and one triggered by international macroeconomic flows in the early 1990's. See the Reserve Bank of New Zealand website, e.g. Figure 1 in https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/-/media/ReserveBank/Files/Publications/Speeches/2017/New-Zealands-net-foreign-liabilities-What-lies-beneath-and-ahead.pdf?revision=c0693fb2-d16e-48df-b72b-c35998adc76d

ReplyDeleteBoth events were a negative re-set to inflation expectations.

I'm going to chime in here. These are just my opinions, fueled by own severe interest in Economics (no Ph.D yet, but I'm on the fence).

ReplyDeleteIt seems to me what these graphs and insights are really about this:

How people and governments react to economic trauma that comes down the pipe, with inflation as the mechanism that triggers that fear. (Deflation triggers the anticipation of extra satiation).

It's interesting you mention time in this post. We learn in school that the Fed likes to keep inflation year over year at 2%, right? We learn the Taylor Rule, etc., etc. It's a cushion against deflation which starts that nasty downward spiral of layoffs-asset/price declines. But here's the thing: 2% inflation as an internal target - and the thinking goes - a little bit of inflation is a good thing because it buys people time to adjust as they see fit.

When inflation even has a hint of going above 2% it starts freaking people out. What is it now? 7%, 8% or so? My home state of California sees gas prices around $6.00 a gallon now. My point is when inflation gets this high, people get real scared because their real nominal incomes start to crater. It starts a game of rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic...

Then there's the Cassandra Syndrome, where people with imperfect Crystal Balls, saying the inflation boogeyman is out to get you. Well, then it appears, and the Cassandras say, "See, we told you so! If you had only done this." Some of this crowd is right and all what should have been done. But here we are.

However, we have to frame this inflation in mess in terms of COVID in the last 2 years (demand suppression and supply chain disruptions), the War in Ukraine, food insecurity, and the impending crypto implosion. There's a lot going on and the Fed really only has a hammer and suffers from recognition lag, which is what the regime under Powell messed up on. They were asleep at the wheel. Doesn't matter what they communicated, they messed up. They don't have the tools they needed to intervene. Ok, so that ship has sailed and sunk to the bottom of the ocean and Powell will have the unfortunate generalized reputation of being incompetent and destroying the economy. Well, it's not there yet. Maybe he pulls victory out of the jaws of defeat.

Anyway, back to the point: when inflation starts going above 2%, the media freaks out, and there's fear. What these awesome graphs Dr. Cochrane shows in my mind is how institutions react to fear, and how they could do better. That's what we're really after: how to calm the storm. The immortal Y = C + I + G + NX isn't going away anytime soon, and C (consumption) as we all know is 66.67 - 70.00% of the economy. That Fiscal Helicopter drop was to prevent a total cratering of the economy because that's all we really had. Sure, better policy would have helped, but how rational are you when you're gripped by fear? Economic rationality sort of goes out the window.

This is where I think AI can help by offering prescriptions that mitigate fear, but we need better rhetoric. Who we believe is critically important. (con't.)

(part 2 of my comment - maybe it is worthy.)

ReplyDeleteIt's doable, but it's a Natural thing to get scared if economic trauma is on the horizon. It's almost the opposite of deflation, where people hold on to cash because they're bargain conscious - they wait to scoop all they can. Inflation at 8% is bad because fear takes over because the perceived response window appears shorter and consumption takes a similar hit. The extra money going into the gas tank could have been used for that video game for your kid, or a pair of shoes your kid desperately needs.

It's messy. As far as deficits and debt are concerned, plenty from Dr. Cochrane on that phenomenon on kicking the can down the road until you run out of road (g > r model). There's a point where there's no more room to maneuver and you hit a wall. Russia had that problem in the late 1990's when bonds were being sold at 125% interest. The IMF had to come in and restore order by plugging a giant hole.

Anyway, yes: fear is real. How people perceive it and react to it is just as important as how they react/respond to incentives.

P.S. Isn't the Phillips Curve a bit stale?

How should we account for drastic change in manufacturing base in the US today compared to all the earlier periods you discuss in this text?

ReplyDeleteRead or watch this:

Deletehttps://www.ted.com/talks/yasheng_huang_does_democracy_stifle_economic_growth/transcript?language=en

How much of this is due to omitting money from the story? Surely we haven't stopped thinking that the price of money is determined by the supply of, and demand for, money. If not, then of course expansionary monetary policy (supply increasing relative to demand) produces a higher price level, and contractionary monetary policy (supply decreasing relative to demand) produces a lower price level. The puzzle about interest rates stems from the fact that lower interest rates can be induced by expansionary policy (via the liquidity effect), or by contractionary policy (via the Fisher effect). If the Fed lowers interest rates by permanently lowering inflation expectations, this will of course lead to lower inflation, since the way the Fed permanently lowers inflation expectations is by permanently slowing money growth. But if they lower interest rates by printing money, this will of course lead to higher inflation. So I think some of this puzzlement about the path of interest rates in relation to the path of inflation stems from not being clear about what is actually going on under the hood.

ReplyDeleteAlso, I wonder whether this idea of passive fiscal policy bakes your result into the cake. Spending is always financed by taxes, the question is merely which taxes and when. Even default is a tax, namely a tax on bondholders. So when you say fiscal policy is passive in the face of monetary policy-induced changes in interest rates, presumably you mean that no taxes will ever be raised by the Treasury to finance higher interest costs, *including* bondholder taxes. Hence by ruling out all other forms of taxation, necessarily the inflation tax makes up the difference.

But when we talk about independent monetary policy, we don't mean fiscal and monetary policy are *statistically* independent. We mean that monetary policymakers credibly commit to never bailing out the Treasury, and focus solely on managing inflation. If you built that into your model, that would take the inflation tax off the table, and if other taxes were off the table too (per 'passive' fiscal policy), then what would happen is a default, which would have no implications for the price level. So you get fiscal control of the price level by assuming that when push comes to shove the Fed will bail out the Treasury. But that's not what anyone who says inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon has in mind. So I'm not sure what the puzzle is supposed to be here.

How does Quantitative Tightening affect this? I see disinflation mentioned but QT unmentioned, perhaps because there aren’t historical comparisons?

ReplyDeleteSurprised there isn't more talk of whether the Fed should correct it's overshoot. Any large over/under-shoot brings with it unintended transfers (currently, the most notable may be from renters to homeowners). Does the Fed simply have no obligation to take that into account and correct? Wouldn't ignoring past errors be equivalent to fiscal policy - picking winners & losers?

ReplyDeletePowell destroyed the deposit classifications, but contrary to Bernanke, money and inflation have always been connected. The rate-of-change in the time series bottomed in the first qtr. of 2020 and peaked in the first qtr. of 2022 (coinciding with the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, Core PCE ).

ReplyDeletePowell destroyed deposit classifications, but contrary to Bernanke money and inflation are still connected. The time series bottomed in the first qtr. of 2020 and peaked in the first qtr. of 2022 (coinciding with the FEDs preferred inflation gauge Core PCE)

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThank you John, for this excellent conference. I enjoyed having this range of papers, issues, policy, and historical development of monetary theory

ReplyDeleteCharts and money supply? Regulations reform? The Fed blah blah. Historical picture-Economists have averted zero major economic failures… the failure of Obama and Biden listed:

ReplyDeleteTotal USA energy production shutdown, Supply chain disrupted, war on small businesses, out of control government spending, zero immigration policy, zero judicial California, Oregon, New York crime jurisprudence, overt media lying and dying in own political agenda, school boards playing Nazi parental rights and protecting libraries offering Gay Story Hour? Who had this great epiphany? Now, this lists only the major government blunders, besides electronic voting corruption…playing with charts and hypotheses (theory has proofs,etc.)ignoring day to day living details and is how social uprising are born.