Don't piss people off unless you have to. Over at Substack.

Sunday, December 31, 2023

Friday, December 29, 2023

Argue Honestly in the Claudine Gay Affair

Post over at Substack. Firing Gay over plagiarism will not fix Harvard.

Thursday, December 28, 2023

Conti on the future of universities

A new post over at Substack, a nice essay by Greg Conti on the future of universities.

Wednesday, December 27, 2023

A Kind Word for the Fed

This is my first post over at Substack. Follow me here and let me know if it isn't working.

The post is in praise of interest on reserves and abundant reserves, with (of course) some suggestions for improvements.

Wednesday, December 20, 2023

Politics by Law

Colorado's Supreme Court kicks Trump off the ballot (WSJ). I wrote earlier forecasting constitutional crisis with next election. Legal chaos is starting right on schedule.

Summary: Both sides are casting their opponents as illegitimate. That justifies profound norm-breaking behavior. Political battles are being fought in the courts, so control of the courts and the judicial system now becomes vital to political success. When you can't afford to lose an election you do anything to win. Scorched earth rules the day.

This affair offers a catch-22 to the Supreme Court. As a partisan chess move, you can't help but admire it. The case is weak, as even the judges voting for it admit. The election is coming up fast. There are many pending state cases to keep Trump off the ballot. The Supreme Court surely does not want to see elections more and more decided by courts. This will likely force the Court to act.

Sunday, December 17, 2023

Bond risk premiums -- certainty found and lost again

This is a second post from a set of comments I gave at the NBER Asset Pricing conference in early November at Stanford. Conference agenda here. My full slides here. First post here, on new-Keynesian models

I commented on "Downward Nominal Rigidities and Bond Premia" by François Gourio and Phuong Ngo. The paper was about bond premiums. Commenting made me realize that I thought I understood the issue, and now I realize I don't at all. Understanding term premiums still seems a fruitful area of research after all these years.

I thought I understood risk premiums

The term premium question is, do you earn more money on average holding long term bonds or short-term bonds? Related, is the yield curve on average upward or downward sloping? Should an investor hold long or short term bonds?

Friday, December 15, 2023

Time for a new (?) theory of regulation

What's the basic story of economic regulation?

Econ 101 courses repeat the benevolent dictator theory of regulation: There is a "market failure," natural monopoly, externality, or asymmetric information. Benevolent regulators craft optimal restrictions to restore market order. In political life "consumer protection" is often cited, though it doesn't fit that economic structure.

Then "Chicago school" scholars such as George Stigler looked at how regulations actually operated. They found "regulatory capture." Businesses get cozy with regulators, and bit by bit regulations end up largely keeping competition down and prices up to benefit existing businesses.

We are, I think, seeing round three, and an opportunity for a fundamentally new basic view of how regulation operates today.

The latest news item to prod this thought is FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr's scathing dissent on the FCC's decision to cancel $885 million contract to Starlink. Via twitter/X:

Wednesday, December 13, 2023

A Vision for the University of Pennsylvania

A group of faculty at Penn have written A Vision for a New Future of the University of Pennsylvania at https://pennforward.com/. They encourage signatures, even if you're not associated with Penn. I signed.

Big picture: Universities stand at a crossroads. Do universities choose pursuit of knowledge, the robust open and uncomfortable debate that requires; excellence and meritocracy, even if as in the past that has meant admitting socially disfavored groups? Or do universities exist to advance, advocate for, and inculcate a particular political agenda? Choose.

Returning to the former will require structural changes, and founding documents are an important part of that rebuilding effort. For example, Penn and Stanford are searching for new presidents. A joint statement by board and president that this document will guide rebuilding efforts could be quite useful in guiding that search and the new Presidents' house-cleaning.

There is some danger in excerpting such a document, but here are a few tasty morsels:

Principles:

Penn’s sole aim going forward will be to foster excellence in research and education.

Specifics:

Friday, December 8, 2023

Sociology Meetings

When Jukka Savolainen wrote about it in the Wall Street Journal I couldn't quite believe it, so I had to go look. Indeed, on the website of the American Sociological Association describing its 2024 annual meeting we have the official "theme" of the meeting

"..sociology as a form of liberatory praxis: an effort to not only understand structural inequities, but to intervene in socio-political struggles."

"To intervene." "Political struggles."

New-Keynesian models, a puzzle of scientific sociology

This post is from a set of comments I gave at the NBER Asset Pricing conference in early November at Stanford. Conference agenda here. My full slides here. There was video, but sadly I took too long to write this post and the NBER took down the conference video.

I was asked to comment on "Downward Nominal Rigidities and Bond Premia" by François Gourio and Phuong Ngo. It's a very nice clean paper, so all I could think to do as discussant is praise it, then move on to bigger issues. These are really comments about whole literatures, not about one paper. One can admire the play but complain about the game.

The paper implements a version of Bob Lucas' 1973 "International evidence" observation. Prices are less sticky in high inflation countries. The Phillips curve more vertical. Output is less affected by inflation. The Calvo fairy visits every night in Argentina. To Lucas, high inflation comes with variable inflation, so people understand that price changes are mostly aggregate not relative prices, and ignore them. Gourio and Ngo use a new-Keynesian model with downwardly sticky prices and wages to express the idea. When inflation is low, we're more often in the more-sticky regime. They use this idea in a model of bond risk premia. Times of low inflation lead to more correlation of inflation and output, and so a different correlation of nominal bond returns with the discount factor, and a different term premium.

I made two points, first about bond premiums and second about new-Keynesian models. Only the latter for this post.

This paper, like hundreds before it, adds a few ingredients on top of a standard textbook new-Keynesian model. But that textbook model has deep structural problems. There are known ways to fix the problems. Yet we continually build on the standard model, rather than incorporate known ways or find new ways to fix its underlying problems.

Problem 1: The sign is "wrong" or at least unconventional.

Wednesday, December 6, 2023

The Income Tax Paradox

The Supreme Court is hearing a case with profound implications for the income tax. WSJ editorial here and good commentary from Ilya Shapiro here.

This issue is naturally contorted into legalisms: What the heck does "apportioned" mean? How is "income" defined legally? I won't wade into that. What are the economic issues? What's the right thing to do here, leaving aside legalisms?

Monday, December 4, 2023

FTPL news: discount and Economist list

Just in time for the holidays, the perfect stocking stuffer -- if you have really big stockings. 30% discount on Fiscal Theory of the Price Level until June 30 2024.

And Fiscal Theory makes the Economist's list of best books for 2023.

Friday, November 24, 2023

Pro Dollarization

With President Milei's election in Argentina, dollarization is suddenly on the table. I'm for it. Here's why.

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

Sunstein redefines "Liberal"

Cass Sunstein has a lovely New York Times essay that tries to give us back the word "Liberal." I hope it works.

Thursday, November 16, 2023

FTPL at SEA

Sunday Nov 19 6-7 PM I will be giving the "Association Lecture" at the Southern Economics Association conference in New Orleans. The topic naturally is "The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level." If you're curious, and will be at the conference, stop by. I now have a pretty good condensed talk about fiscal theory!

Sunday, November 5, 2023

Lukianoff and Schlott on Cancellation

Last week I was honored to be moderator for a discussion with Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott on their new book "Canceling the American Mind" at the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco. Link here, if the embed above doesn't work

Here are my questions. I shared them with Greg and Rickki ahead of time, so the actual questions are a bit shorter. But this may give you some interesting background, and I think they're good questions to ponder in general.

Friday, October 27, 2023

Prices vs. inflation and a mortgage puzzle

Mickey Levy's excellent WSJ oped leaves some thoughts.

Inflation has fallen, though I still suspect it may get stuck around 3-4%. But prices "are 18.9% higher than its [their] pre-pandemic level." And some important prices have risen even more. "Rental costs continue to rise in lagged response to the 46.1% surge in home prices." Those who are taking a victory lap about the end of inflation (the rate of change of prices) are befuddled by continuing consumer (and voter) anger.

Well, prices are not the same thing as inflation.

Evergreen expectations

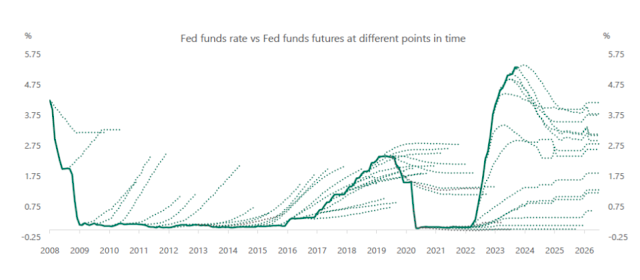

A lovely plot from the always interesting Torsten Slok. The graph shows the actual federal funds rate, together with the path of "expected" funds rate implicit in fed funds futures market prices. (Roughly speaking the futures contract is a bet on where the Fed funds rate will be at various dates in the future. If you want to bloviate about what the Fed will do, it's easy to put your money where your mouth is!)

A lot of graphs look like this, including the Fed's "dot plot" projections of where interest rates will go, inflation forecasts, and longer term interest rate forecasts based on the yield curve (yields on 10 year bonds imply a forecast of one year bonds over the 10 year period.) Just change the labels.

Sunday, October 22, 2023

Leonhardt on investment

David Leonhardt's pean to investment in the Sunday NY Times Magazine starts well:

A cross-country trip today typically takes more time than it did in the 1970s. The same is true of many trips within a region or a metropolitan area....Door to door, cross-country journeys often last 10 or even 12 hours.

Friday, October 20, 2023

Bhattacharya on Covid censorship

A week ago Jay Bhattacharya gave a great talk at the weekly Stanford Classical Liberalism workshop. (Link in case the embed doesn't work.) He detailed the story of government+media Covid censorship, along with the dramatic injunction in the Missouri v. Biden case. The discovery in that case alone, detailing how the administration used the threat of arbitrary regulatory retaliation to get tech companies to censor covid information -- along with other matters, including the Hunter Biden laptop -- is astonishing. We now know what they did, no matter what judges say about its technical legality.

Wednesday, October 18, 2023

Political prisoner dilemma

This is a draft oped. It didn't make it as events in Israel are now consuming attention. But sooner or later we need to elect a president and live with the results. I went light on the economics, but you can see the basic game theory of the analysis. It amplifies some comments I made on Goodfellows.

****

If, as it appears, the election will come down to Trump vs. Biden, the US is headed for a constitutional crisis, and the social, and political chaos that implies. Like prisoners of the economists’ dilemma, there seems no easy way out.

Whichever wins, the others’ partisans will pronounce the president to be fundamentally illegitimate. In turn, Illegitimacy justifies and emboldens scorched-earth tactics, more norm-busting and institution-destruction.

Friday, October 13, 2023

Heterogeneous Agent Fiscal Theory

Today, I'll add an entry to my occasional reviews of interesting academic papers. The paper: "Price Level and Inflation Dynamics in Heterogeneous Agent Economies," by Greg Kaplan, Georgios Nikolakoudis and Gianluca Violante.

One of the many reasons I am excited about this paper is that it unites fiscal theory of the price level with heterogeneous agent economics. And it shows how heterogeneity matters. There has been a lot of work on "heterogeneous agent new-Keynesian" models (HANK). This paper inaugurates heterogeneous agent fiscal theory models. Let's call them HAFT.

Monday, August 28, 2023

Interest rates and inflation part 3: Theory

This post takes up from two previous posts (part 1; part 2), asking just what do we (we economists) really know about how interest rates affect inflation. Today, what does contemporary economic theory say?

As you may recall, the standard story says that the Fed raises interest rates; inflation (and expected inflation) don't immediately jump up, so real interest rates rise; with some lag, higher real interest rates push down employment and output (IS); with some more lag, the softer economy leads to lower prices and wages (Phillips curve). So higher interest rates lower future inflation, albeit with "long and variable lags."

Higher interest rates -> (lag) lower output, employment -> (lag) lower inflation.

In part 1, we saw that it's not easy to see that story in the data. In part 2, we saw that half a century of formal empirical work also leaves that conclusion on very shaky ground.

As they say at the University of Chicago, "Well, so much for the real world, how does it work in theory?" That is an important question. We never really believe things we don't have a theory for, and for good reason. So, today, let's look at what modern theory has to say about this question. And they are not unrelated questions. Theory has been trying to replicate this story for decades.

The answer: Modern (anything post 1972) theory really does not support this idea. The standard new-Keynesian model does not produce anything like the standard story. Models that modify that simple model to achieve something like result of the standard story do so with a long list of complex ingredients. The new ingredients are not just sufficient, they are (apparently) necessary to produce the desired dynamic pattern. Even these models do not implement the verbal logic above. If the pattern that high interest rates lower inflation over a few years is true, it is by a completely different mechanism than the story tells.

I conclude that we don't have a simple economic model that produces the standard belief. ("Simple" and "economic" are important qualifiers.)

The simple new-Keynesian model

Thursday, August 10, 2023

Interest rates and inflation part 2: Losing faith in VARs

(This post continues part 1 which just looked at the data. Part 3 on theory is here)

When the Fed raises interest rates, how does inflation respond? Are there "long and variable lags" to inflation and output?

There is a standard story: The Fed raises interest rates; inflation is sticky so real interest rates (interest rate - inflation) rise; higher real interest rates lower output and employment; the softer economy pushes inflation down. Each of these is a lagged effect. But despite 40 years of effort, theory struggles to substantiate that story (next post), it's had to see in the data (last post), and the empirical work is ephemeral -- this post.

The vector autoregression and related local projection are today the standard empirical tools to address how monetary policy affects the economy, and have been since Chris Sims' great work in the 1970s. (See Larry Christiano's review.)

I am losing faith in the method and results. We need to find new ways to learn about the effects of monetary policy. This post expands on some thoughts on this topic in "Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest Rates," several of my papers from the 1990s* and excellent recent reviews from Valerie Ramey and Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson, who eloquently summarize the hard identification and computation troubles of contemporary empirical work.

Maybe popular wisdom is right, and economics just has to catch up. Perhaps we will. But a popular belief that does not have solid scientific theory and empirical backing, despite a 40 year effort for models and data that will provide the desired answer, must be a bit less trustworthy than one that does have such foundations. Practical people should consider that the Fed may be less powerful than traditionally thought, and that its interest rate policy has different effects than commonly thought. Whether and under what conditions high interest rates lower inflation, whether they do so with long and variable but nonetheless predictable and exploitable lags, is much less certain than you think.

Monday, August 7, 2023

Blinder, supply shocks, and nominal anchors

An a recent WSJ oped (which I will post here when 30 days have passed), I criticized the "supply shock" theory of our current inflation. Alan Blinder responds in WSJ letters

First, Mr. Cochrane claims, the supply-shock theory is about relative prices (that’s true), and that a rise in some relative price (e.g., energy) “can’t make the price of everything go up.” This is an old argument that monetarists started making a half-century ago, when the energy and food shocks struck. It has been debunked early and often. All that needs to happen is that when energy-related prices rise, many other prices, being sticky downward, don’t fall. That is what happened in the 1970s, 1980s and 2020s.

Second, Mr. Cochrane claims, the supply-shock theory “predicts that the price level, not the inflation rate, will return to where it came from—that any inflation should be followed by a period of deflation.” No. Not unless the prices of the goods afflicted by supply shocks return to the status quo ante and persistent inflation doesn’t creep into other prices. Neither has happened in this episode.

When economists disagree about fairly basic propositions, there must be an unstated assumption about which they disagree. If we figure out what it is, we can think more productively about who is right.

I think the answer here is simple: To Blinder there is no "nominal anchor." In my analysis, there is. This is a question about which one can honorably disagree. (WSJ opeds have a hard word limit, so I did not have room for nuance on this issue.)

Sunday, August 6, 2023

Rangvid on housing inflation

(This post is an interlude between history and VARs)

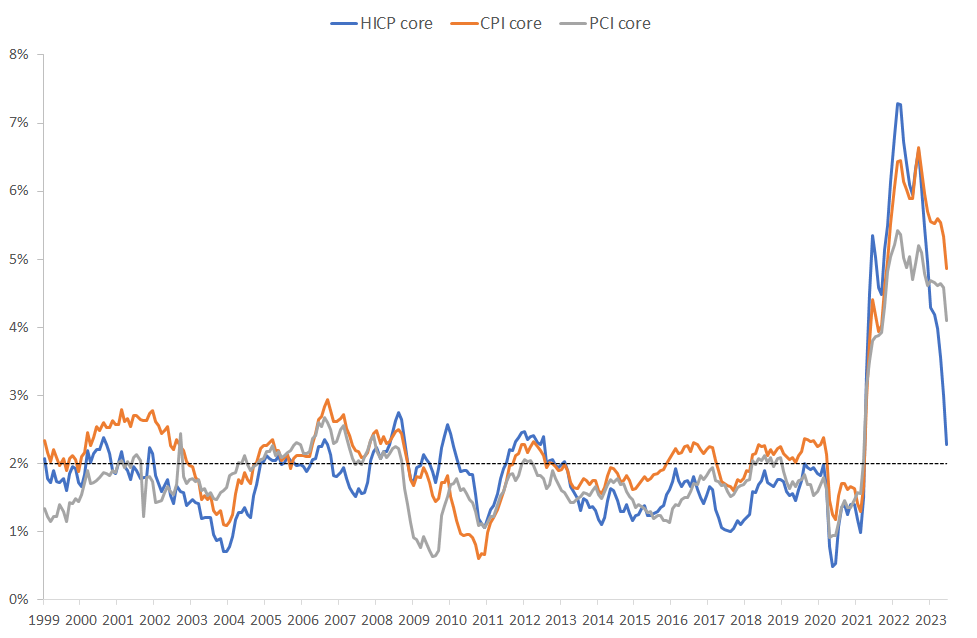

Jesper Rangvid has a great blog post today on different inflation measures.

CPI and PCE core inflation (orange and gray) are how the US calculates inflation less food and energy, but including housing. We do an economically sophisticated measure that tries to measure the "cost of housing" by rents for those who rent, plus how much a homeowner pays by "renting" the house to him or herself. You can quickly come up with the plus and minus of that approach, especially for looking at month to month trends in inflation. Europe in the "HICP core" line doesn't even try and leaves owner occupied housing out altogether.

Jesper's point: if you measure inflation Europe's way, US inflation is already back to 2%. The Fed can hang out a "mission accomplished" banner. (Or, in my view, a "it went away before we really had to do anything serious about it" banner.) And, since he writes to a European audience, Europe has a long way to go.

A few deeper (and slightly grumpier) points:

Saturday, August 5, 2023

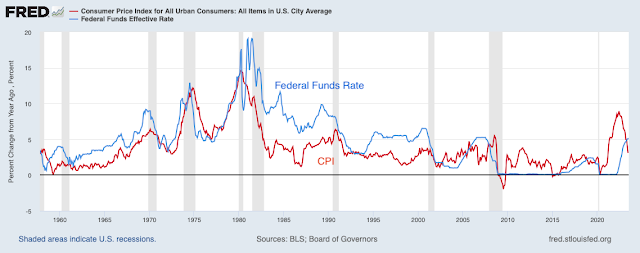

Interest rates and inflation -- part 1

Today I begin a three part series exploring interest rates and inflation. (Part 2 empirical work, Part 3 theory)

How does the Fed influence inflation? Is the recent easing of inflation due to Fed policy, or happening on its own? To what extent should we look just to the Fed to bring inflation under control going forward?

The standard story: The Fed raises the interest rate. Inflation is somewhat sticky. (Inflation is sticky. This is important later.) Thus the real interest rate also rises. The higher real interest rate softens the economy. And a softer economy slowly lowers inflation. The effect happens with "long and variables lags," so a higher interest rate today lowers inflation only a year or so from now.

interest rate -> (lag) softer economy -> (lag) inflation declines

This is a natural heir to the view Milton Friedman propounded in his 1968 AEA presidential address, updated with interest rates in place of money growth. A good recent example is Christina and David Romer's paper underlying her AEA presidential address, which concludes of current events that as a result of the Fed's recent interest-rate increases, "one would expect substantial negative impacts on real GDP and inflation in 2023 and 2024."

This story is passed around like well worn truth. However, we'll see that it's actually much less founded than you may think. Today, I'll look at simple facts. In my next post, I'll look at current empirical work, and we'll find that support for the standard view is much weaker than you might think. Then, I'll look at theory. We'll find that contemporary theory (i.e. for the last 30 years) is strained to come up with anything like the standard view.

Wednesday, August 2, 2023

Fitch is right

(Updated to fix numbers.) Fitch is right to downgrade the US. Read the sober report. But there are a few other reasons, or emphasis they might have added.

- The inflationary default.

Inflation is the economic equivalent of a partial default. The debt was sold under a 2% inflation target, and people expected that or less inflation. The government borrowed and printed $5 Trillion with no plan to pay it back, devaluing the outstanding debt as a result. Cumulative inflation so far means debt is repaid in dollars that are worth 10% less than if inflation had been* 2%. That's economically the same as a 10% haircut.

Thursday, July 27, 2023

On the 2% inflation target

Project Syndicate asked Mike Boskin, Brigitte Granville, Ken Rogoff and me whether 2% is the right inflation target. See the link for the other views. I pretty much agree with them in the short run -- don't mess with it -- but took a different long run view. Apparently Volcker and Greenspan were fans of price level targeting and hoped to get there eventually, which is the sort of long run approach I took here.

I also emphasize that any inflation target is (of course) a joint target of fiscal as well as monetary policy. Fiscal policy needs to commit to repay debt at the inflation target.

My view:

No, 2% is not the right target. Central banks and governments should target the price level. That means not just pursuing 0% inflation, but also, when inflation or deflation unexpectedly raise or lower the price level, gently bringing the price level back to its target. (I say “and governments” because inflation control depends on fiscal policy, too.)

The price level measures the value of money. We don’t shorten the meter 2% every year. Confidence in the long-run price level streamlines much economic, financial, and monetary activity. The corresponding low interest rates allow companies and banks to stay awash in liquidity at low cost. A commitment to repay debt without inflation also makes government borrowing easier in times of war, recession, or crisis.

Wednesday, July 19, 2023

Electric vehicles, carbon taxes, supply and demand, virtue signals, and China

If you have not been paying attention, our government has decided that all electric vehicles are the solution to the climate problem. At least as long as they are made in the US with union labor and benefits. California has committed to banning the sale of anything else. In today's post, a few tidbits from my daily WSJ reading on the subject.

From Holman Jenkins on electric cars:

If the goal were to reduce emissions, the world would impose a carbon tax. Then what kind of EVs would we get? Not Teslas but hybrids like Toyota’s Prius. “A wheelbarrow full of rare earths and lithium can power either one [battery-powered car] or over 90 hybrids, but, uh, that fact seems to be lost on policymakers,” a California dealer recently emailed me.

[Note: that wheelbarrow of rare earths comes from multiple truckloads of actual rocks. Also see original for links.]

...The same battery minerals in one Tesla can theoretically supply 37 times as much emissions reduction when distributed over a fleet of Priuses.

Thursday, July 13, 2023

Writing tidbit

From Joseph Epstien's oped in the July 13 WSJ on Biden v Trump (please, dear Lord, no)

Each man has risen to the presidency thanks, mostly, to the unattractiveness of his electoral opponent. Each man was elected as a lesser-evil choice, yet both have succeeded in vastly polluting the tone of our country’s political life. Lesser-evil choices sometimes turn out to be evil enough.

Low and seedy are the corruptions of which Messrs. Trump and Biden have been accused: molesting women, entering into dubious financial dealings with foreign corporations and governments, cavalierly mishandling important documents, and more.

My italics. I'm not here today on content, but just on writing. I make mental notes of little writing tricks that might embellish my prose.

I liked the first one, just because it's such a beautiful catchy phrase. I'm not sure what the general principle is, but I'd like to come up with more prose like that.

The second one has a clearer lesson. The usual rule is, write your sentences forward. Or, more likely, edit your sentences to be forwards. You should quickly turn that one around to "The corruptions of which Messrs. Trump and Biden have been accused are low and seedy." Or, better, through it changes the subject a bit, "Messrs. Trump and Biden have been accused of low and seedy corruptions." 99% of the time you should do that.

But not this time. Look how beautiful that backward sentence is. There must be some biblical quote it refers to. Maybe readers can come up with the allusions.

Don't do it all the time. But rules are made to be broken, if you really know what you're doing. Which Epstein clearly does.

Freeman on Mills on IEA on battery powered cars

James Freeman's always excellent "best of the web" WSJ column today covers a Manhattan Institute report by Mark Mills itself referencing material deep in side an International Energy Agency report on battery powered electric cars. Like corn ethanol, this enthusiasm may also pass.

The economic and environmental costs of batteries are slowly seeping out. One of my pet peeves in all of our command-and-control climate policy is that any comprehensive quantification of costs and benefits seems so rare, or at least so hidden. How many dollars for how many tons of carbon -- and especially the latter: how many tons of carbon, really, all in, including making the cars? (California only counts tailpipe emissions!) I have seen guesstimates that electric cars only breakeven in their carbon emissions at 50,000-70,000 miles. And, the point of the article, those estimates are likely undercounts especially if there is a huge expansion.

Parts I found interesting and novel:

For all of history, the costs of a metal in both dollar and environmental terms are dictated primarily by ore grades, i.e., the share of the rock dug up that contains the metal sought... Ore grade is what accounts for the differences in the cost per pound of gold, $15,000, and iron, $0.05. The former ore grades are typically below 0.001% and the latter over 50%.

Tuesday, July 11, 2023

New York Times on HANK, and questions

By the standards of mainstream media coverage of technical economics, Peter Coy's coverage of HANK (Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian) models in the New York Times was actually pretty good.

1) Representative agents and distributions.

Yes, it starts with the usual misunderstanding about "representative agents," that models assume we are all the same. Some of this is the standard journalist's response to all economic models: we have simplified the assumptions, we need more general assumptions. They don't understand that the genius of economic theory lies precisely in finding simplified but tractable assumptions that tell the main story. Progress never comes from putting more ingredients and stirring the pot to see what comes out. (I mean you, third year graduate students looking for a thesis topic.)

But in this case many economists are also confused on this issue. I've been to quite a few HANK seminars in which prominent academics waste 10 minutes or so dumping on the "assumption that everyone is identical."

There is a beautiful old theorem, called the "social welfare function." (I learned this in graduate school in fall 1979, from Hal Varian's excellent textbook.) People can have almost arbitrarily different preferences (utility functions), incomes and shocks, companies can have almost arbitrarily different characteristics (production functions), yet the aggregate economy behaves as if there is a single representative consumer and representative firm. The equilibrium path of aggregate consumption, output, investment, employment, and the prices and interest rates of that equilibrium are the same as those of an economy where everyone and every firm is the same, with a "representative agent" consumption function and "representative firm" production function. Moreover, the representative agent utility function and representative firm production function need not look anything like those of any particular individual person and firm. If I have power utility and you have quadratic utility, the economy behaves as if there is a single consumer with something in between.

Defining the job of macroeconomics to understand the movement over time of aggregates -- how do GDP, consumption, investment, employment, price level, interest rates, stock prices etc. move over time, and how do policies affect those movements -- macroeconomics can ignore microeconomics. (We'll get back to that definition in a moment.)

Monday, July 10, 2023

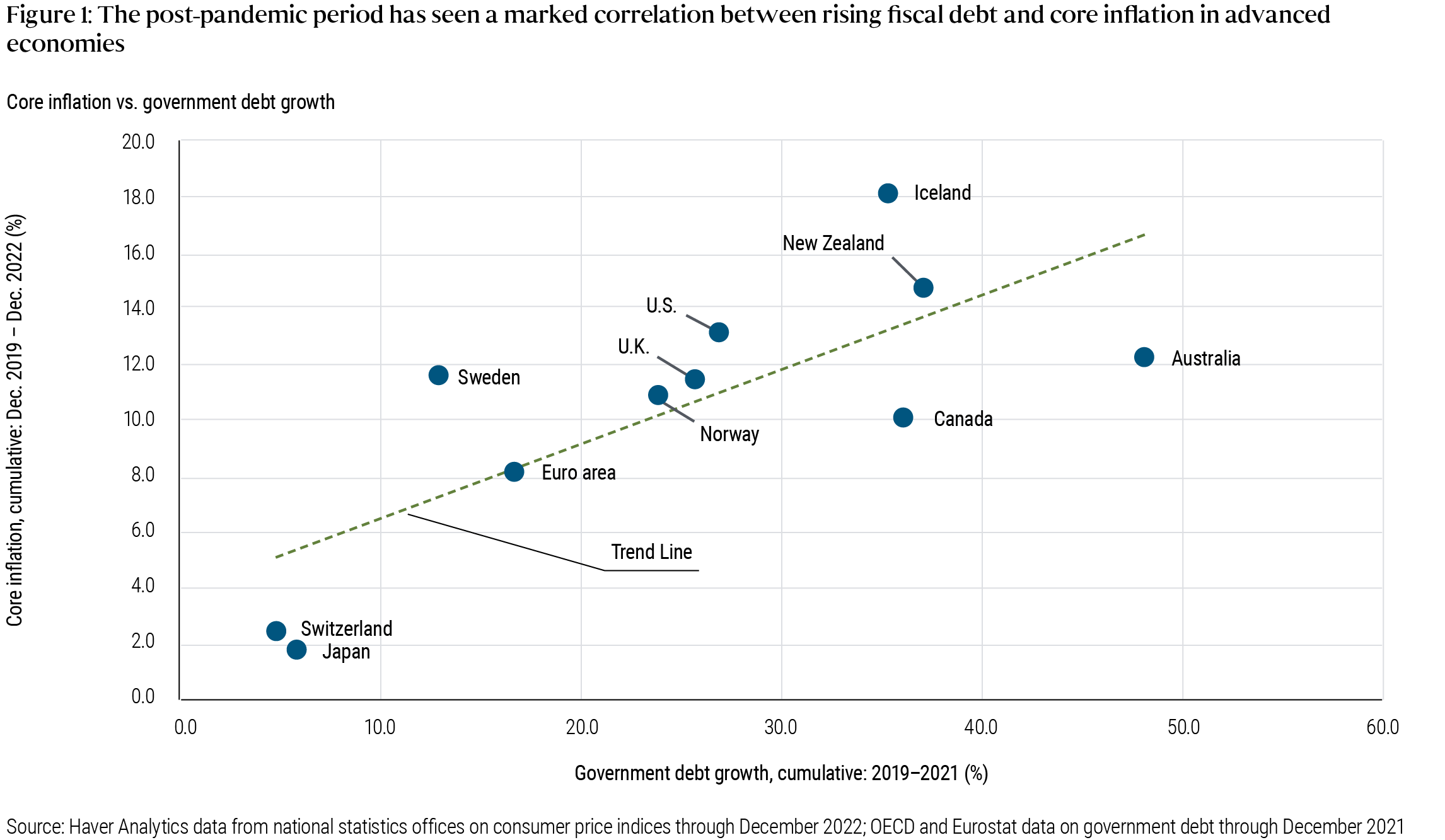

Inflation and debt across countries

Peder Beck-Friis and Richard Clarida at Pimco have a nice blog post on the recent inflation, including the above graph. I have wondered, and been asked, if the differences across countries in inflation lines up with the size of the covid fiscal expansion. Apparently yes.

Wednesday, July 5, 2023

Fiscal inflation and interest rates

Economics is about solving lots of little puzzles. At a July 4th party, a super smart friend -- not a macroeconomist -- posed a puzzle I should have understood long ago, prompting me to understand my own models a little better.

How do we get inflation from the big fiscal stimulus of 2020-2021, he asked? Well, I answer, people get a lot of government debt and money, which they don't think will be paid back via higher future taxes or lower future spending. They know inflation or default will happen sooner or later, so they try to get rid of the debt now while they can rather than save it. But all we can do collectively is to try to buy things, sending up the price level, until the debt is devalued to what we expect the government can and will pay.

OK, asked my friend, but that should send interest rates up, bond prices down, no? And interest rates stayed low throughout, until the Fed started raising them. I mumbled some excuse about interest rates never being very good at forecasting inflation, or something about risk premiums, but that's clearly unsatisfactory.

Of course, the answer is that interest rates do not need to move. The Fed controls the nominal interest rate. If the Fed keeps the short term nominal interest rate constant, then nominal yields of all bonds stay the same, while fiscal inflation washes away the value of debt. I should have remembered my own central graph:

This is the response of the standard sticky price model to a fiscal shock -- a 1% deficit that is not repaid by future surpluses -- while the Fed keeps interest rates constant. The solid line is instantaneous inflation, while the dashed line gives inflation measured as percent change from a year ago, which is the common way to measure it in the data.Monday, June 19, 2023

Hope from the left

One ray of hope in the current political scene comes from the land of deep blue. However one views the immense expenditure on solar panels, windmills and electric cars, (produced in the US by US union labor, of course), plus forced electrification of heat and cooking, a portion of the blue-state left has noticed that this program cannot possibly work given laws and regulations that have basically shut down all new construction. And a substantial reform may follow.

I am prodded to write by Ezra Kleins' interesting oped in the New York Times, "What the Hell Happened to the California of the ’50s and ’60s?," a question repeatedly asked to Governor Gavin Newsom. The answer is, of course "you happened to it." For those who don't know, California in the 50s and 60s was famous for quickly building new dams, aqueducts, freeways, a superb public education system, and more.

Gavin Newsom states the issue well.

"..we need to build. You can’t be serious about climate and the environment without reforming permitting and procurement in this state.”

You can't be serious about business, housing, transportation, wildfire control, water, and a whole lot else without reforming permitting and procurement, but heck it's a start.

Sunday, June 18, 2023

The perennial fantasy

Two attacks, and one defense, of classical liberal ideas appeared over the weekend. "War and Pandemic Highlight Shortcomings of the Free-Market Consensus" announces Patricia Cohen on p.1 of the New York Times news section. As if the Times had ever been part of such a "consensus." And Deirdre McCloskey reviews Simon Johnson and Daron Acemoglu's "Power and Progress," whose central argument is, per Deirdre, "The state, they argue, can do a better job than the market of selecting technologies and making investments to implement them." (I have not yet read the book. This is a review of the review only.)

I'll give away the punchline. The case for free markets never was their perfection. The case for free markets always was centuries of experience with the failures of the only alternative, state control. Free markets are, as the saying goes, the worst system; except for all the others.

In this sense the classic teaching of economics does a disservice. We start with the theorem that free competitive markets can equal -- only equal -- the allocation of an omniscient benevolent planner. But then from week 2 on we study market imperfections -- externalities, increasing returns, asymmetric information -- under which markets are imperfect, and the hypothetical planner can do better. Regulate, it follows. Except econ 101 spends zero time on our extensive experience with just how well -- how badly -- actual planners and regulators do. That messy experience underlies our prosperity, and prospects for its continuance.

Starting with Ms. Cohen at the Times,

The economic conventions that policymakers had relied on since the Berlin Wall fell more than 30 years ago — the unfailing superiority of open markets, liberalized trade and maximum efficiency — look to be running off the rails.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the ceaseless drive to integrate the global economy and reduce costs left health care workers without face masks and medical gloves, carmakers without semiconductors, sawmills without lumber and sneaker buyers without Nikes.

That there ever was a "consensus" in favor of "the unfailing superiority of open markets, liberalized trade and maximum efficiency" seems a mighty strange memory. But if the Times wants to think now that's what they thought then, I'm happy to rewrite a little history.

Face masks? The face mask snafu in the pandemic is now, in the Times' rather hilarious memory, the prime example of how a free and unfettered market fails. It was a result of "the ceaseless drive to integrate the global economy and reduce costs?"

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

The barn door

Kevin Warsh has a nice WSJ oped warning of financial problems to come. The major point of this essay: "countercyclical capital buffers" are another bright regulatory idea of the 2010s that now has fallen flat.

As in previous posts, a lot of banks have lost asset value equal or greater than their entire equity due to plain vanilla interest rate risk. The ones that haven't run are now staying afloat only because you and me keep our deposits there at ridiculously low interest rates. Commercial real estate may be next. Perhaps I'm over-influenced by the zombie-apocalypse goings on in San Francisco -- $755 million default on the Hilton and Parc 55, $558 million default on the whole Westfield mall after Nordstrom departed and on and on. How much of this debt is parked in regional banks? I would have assumed that the Fed's regulatory army could see something so obvious coming, but since they completely missed plain vanilla interest rate risk, and the fact that you don't have to stand in line any more to run on your bank, who knows?

So, banks are at risk; the Fed now knows it, and is reportedly worried that more interest rates to lower inflation will cause more problems. To some extent that's a feature not a bug -- the whole theory behind the Fed lowering inflation is that higher interest rates "cool economic activity," i.e. make banks hesitant to lend, people lose their jobs, and through the Phillips curve (?) inflation comes down. But the Fed wants a minor contraction, not full-on 2008. (That did bring inflation down though!)

I don't agree with all of Kevin's essay, but I always cherry pick wisdom where I find it, and there is plenty. On what to do:

Ms. Yellen and the other policy makers on the Financial Stability Oversight Council should take immediate action to mitigate these risks. They should promote the private recapitalization of small and midsize banks so they survive and thrive.

Yes! But. I'm a capital hawk -- my answer is always "more." But we shouldn't be here in the first place.

Monday, June 12, 2023

Papers: Dew-Becker on Networks

I've been reading a lot of macro lately. In part, I'm just catching up from a few years of book writing. In part, I want to understand inflation dynamics, the quest set forth in "expectations and the neutrality of interest rates," and an obvious next step in the fiscal theory program. Perhaps blog readers might find interesting some summaries of recent papers, when there is a great idea that can be summarized without a huge amount of math. So, I start a series on cool papers I'm reading.

Today: "Tail risk in production networks" by Ian Dew-Becker, a beautiful paper. A "production network" approach recognizes that each firm buys from others, and models this interconnection. It's a hot topic for lots of reasons, below. I'm interested because prices cascading through production networks might induce a better model of inflation dynamics.

(This post uses Mathjax equations. If you're seeing garbage like [\alpha = \beta] then come back to the source here.)

To Ian's paper: Each firm uses other firms' outputs as inputs. Now, hit the economy with a vector of productivity shocks. Some firms get more productive, some get less productive. The more productive ones will expand and lower prices, but that changes everyone's input prices too. Where does it all settle down? This is the fun question of network economics.

Ian's central idea: The problem simplifies a lot for large shocks. Usually when problems are complicated we look at first or second order approximations, i.e. for small shocks, obtaining linear or quadratic ("simple") approximations.

Friday, June 9, 2023

The Fed and the Phillips curve

I just finished a new draft of "Expectations and the neutrality of interest rates," which includes some ruminations on inflation that may be of interest to blog readers.

A central point of the paper is to ask whether and how higher interest rates lower inflation, without a change in fiscal policy. That's intellectually interesting, answering what the Fed can do on its own. It's also a relevant policy question. If the Fed raises rates, that raises interest costs on the debt. What if Congress refuses to tighten to pay those higher interest costs? Well, to avoid a transversality condition violation (debt that grows forever) we get more inflation, to devalue outstanding debt. That's a hard nut to avoid.

But my point today is some intuition questions that come along the way. An implicit point: The math of today's macro is actually pretty easy. Telling the story behind the math, interpreting the math, making it useful for policy, is much harder.

1. The Phillips curve

The Phillips curve is central to how the Fed and most policy analysts think about inflation. In words, inflation is related to expected future inflation and by some measure if economic tightness, factor \(x\). In equations, \[ \pi_t = E_t \pi_{t+1} + \kappa x_t.\] Here \(x_t\) represents the output gap (how much output is above or below potential output), measures of labor market tightness like unemployment (with a negative sign), or labor costs. (Fed Governor Chris Waller has a great speech on the Phillips curve, with a nice short clear explanation. There are lots of academic explanations of course, but this is how a sharp sitting member of the FOMC thinks, which is what we want to understand. BTW, Waller gave an even better speech on climate and the Fed. Go Chris!)

So how does the Fed change inflation? In most analysis, the Fed raises interest rates; higher interest rates cool down the economy lowering factor x; that pushes inflation down. But does the equation really say that?

Thursday, June 8, 2023

Cost Benefit Comments

The Biden Administration is proposing major changes to cost-benefit analysis used in all regulations. The preamble here, and the full text here. It is open for public comments until June 20.

Economists don't often comment on proposed regulations. We should do so more often. Agencies take such comments seriously. And they can have an afterlife. I have seen comments cited in litigation and by judicial decisions. Even if you doubt the Biden Administration's desire to hear you on cost-benefit analysis, a comment is a marker that the inevitable eventual Supreme Court case might well consider. Comments tend only to come from interested parties and lawyers. Regular economists really should comment more often. I don't do it enough either.

You can see existing comments: Search for Circular A-4 updates to get to https://www.regulations.gov/docket/OMB-2022-0014, then select “browse all comments.” (Thanks to a good friend who sent this tip.)

Take a look at comments from an MIT team led by Deborah Lucas here and by Josh Rauh. These are great models of comments. You don't have to review everything. Make one good point.

Cost benefit analysis is useful even if imprecise. Lots of bright ideas in Washington (and Sacramento!) would struggle to document any net benefits at all. Yes, these exercises can lie, cheat, and steal, but having to come up with a quantitative lie can lay bare just how hare-brained many regulations are.

Monday, June 5, 2023

Stephens at Chicago; effective organizations

Brett Stephens gave a great commencement speech (NYT link, HT Luis Garicano) at the University of Chicago. One part stood out to me, and worthy of comment. Bret starts with the problem of Groupthink:

Why did nobody at Facebook — sorry, Meta — stop Mark Zuckerberg from going all in on the Metaverse, possibly the worst business idea since New Coke? Why were the economists and governors at the Federal Reserve so confident that interest rates could remain at rock bottom for years without running a serious risk of inflation? Why did the C.I.A. believe that the government of Afghanistan could hold out against the Taliban for months but that the government of Ukraine would fold to the Russian Army in days? Why were so few people on Wall Street betting against the housing market in 2007? Why were so many officials and highly qualified analysts so adamant that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction? Why were so many people convinced that overpopulation was going to lead to catastrophic food shortages, and that the only sensible answers were a one-child policy and forced sterilizations?

Oh, and why did so many major polling firms fail to predict Donald Trump’s victory in 2016?

Conspicuous institutional failures are the question of our age We could add the SBV regulatory fiasco, the 2007 financial regulatory failure, the CDC FDA and numerous governments under Covid, and many more. Systemic incompetence doesn't just include disasters, but ongoing wounds from the Jones act to California's billions wasted on obviously ineffective homeless spending.

Thursday, May 25, 2023

Work requirements

The debate over work requirements for social programs is hot and heavy. I'll chime in there as I don't think even the Wall Street Journal Editorial pages have stated the issue clearly from an economic point of view. As usual, it's getting obfuscated in a moral cloud by both sides: How could you be so heartless as to force unfortunate people to work, vs. how immoral it is to subsidize indolence, and value of the "culture" of self-sufficiency.

Economics, as usual, offers a straightforward value-free way to think about the issue: Incentives. When you put all our social programs together, low income Americans face roughly 100% marginal tax rates. Earn an extra dollar, lose a dollar of benefits. It's not that simple, of course, with multiple cliffs of infinite tax rates (earn an extra cent, lose a program entirely), and depends on how many and which programs people sign up for. But the order of magnitude is right.

The incentive effect is clear: don't work (legally). As Phil Gramm and Mike Solon report,

Since 1967, average inflation-adjusted transfer payments to low-income households—the bottom 20%—have grown from $9,677 to $45,389. During that same period, the percentage of prime working-age adults in the bottom 20% of income earners who actually worked collapsed from 68% to 36%.

36%. The latter number is my main point, we'll get to cost later. Similarly, the WSJ points to a report by Jonathan Bain and Jonathan Ingram at the Foundation for Government Accountability that

there are four million able-bodied adults without dependents on food stamps, and three in four don’t work at all. Less than 3% work full-time.

3%.

Incentives are a budget constraint to government policy, hard and immutable. Your feelings about people one way or another do not move the incentives at all. A gift of money with an income phase-out leads people to work less, and to require more gifts of money. That's just a fact.

What to do?

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Hoover Monetary Policy Conference Videos

The videos from the Hoover Monetary Policy Conference are now online here. See my previous post for a summary of the conference.

The big picture is now clearer to me. Phil Jefferson rightly asked, what do you mean off track? Monetary policy is doing fine. Interest rates are, in his view, where they should be. He argued the case well.

But now I have an answer: The Fed has had three significant institutional failures: 1) Its inflation target is 2%, yet inflation exploded to 8%. The Fed did not forecast it, and did not see it even as it was happening. (Nor did many other forecasters, pointing to deeper conceptual problems.) 2) In the SVB and subsequent mess, the Fed's regulatory apparatus did not see or do anything about plain vanilla interest-rate risk combined with uninsured deposits. 3) I add a third, that nobody else seems to complain about: In 2020 starting with treasury markets, moving on to money market funds, state and local financing, and then an astonishing "whatever it takes" that corporate bond prices shall not fall, the Fed already revealed that the Dodd-Frank machinery was broken. (Will commercial real estate be next?)

Yet there is very little appetite for self-examination or even external examination. How did a good institution, filled with good, honest, smart and devoted public servants fail so badly? That's not "off-track" that's a derailment.

Well, two sessions at the conference begin to ask those questions, and the others aimed at the same issues. Hopefully they will prod the Fed to do so as well, or at least to be interested in other's answers to those questions.

(My minor contributions: on why the Taylor rule is important here, where I think I did a pretty good job; and comments on why inflation forecasts went so wrong at 1:00:16 here.)

Bradley Prize speech, video, and thanks

The videos and speeches of the Bradley prize winners are up. My video here (Grumpy in a tux!), also the speech which I reproduce below. All the videos and speeches here (Betsy DeVos and Nina Shea) My previous interview with Rick Graeber, head of the Bradley foundation.

Bradley also made a nice introduction video with photos from my childhood and early career. (A link here to the introduction video and speech together.) And to avoid us spending all our talks on thanking people, they had us write out a separate thanks. That seems not to be up yet, but I include mine below. I am very thankful, humbled to be included in such august company, and not so boorish that I would not have spent my whole talk without mentioning that, absent the separate opportunity to say so.

Bradley prize remarks (i.e. condense three decades of policy writing into 10 minutes):

Creeping stagnation ought to be recognized as the central economic issue of our time. Economic growth since 2000 has fallen almost by half compared with the last half of the 20th Century. The average American’s income is already a quarter less than under the previous trend. If this trend continues, lost growth in fifty years will total three times today’s economy. No economic issue — inflation, recession, trade, climate, income diversity — comes close to such numbers.

Growth is not just more stuff, it’s vastly better goods and services; it’s health, environment, education, and culture; it’s defense, social programs, and repaying government debt.

Why are we stagnating? In my view, the answer is simple: America has the people, the ideas, and the investment capital to grow. We just can’t get the permits. We are a great Gulliver, tied down by miles of Lilliputian red tape.

Walter Russell Mead and Grapes of Wrath Episode II

Walter Russell Mead has a nice essay in Tablet on California. This excerpt struck me. You too were probably dragged through "Grapes of Wrath" at some point in school, or you've seen the movie. But what happens next? Mead's insight hadn't occurred to me. Spoiler:

Ma Joad might have ended up as the “Little Old Lady From Pasadena,” leaving her garden of white gardenias to become the terror of Colorado Boulevard in her ruby-red Dodge. Rose of Sharon would be a Phyllis Schlafly-loving Reagan activist reunited with her husband, now owner of a small chain of franchise fast-food outlets.

A longer excerpt:

John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath chronicled the suffering of a group of bankrupt former farmers fleeing the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma to arrive, desperate and penniless, in an unwelcoming California.

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Bob Lucas and his papers

My first post described a few anecdotes about what a warm person Bob Lucas was, and such a great colleague. Here I describe a little bit of his intellectual influence, in a form that is I hope accessible to average people.

The “rational expectations” revolution that brought down Keynesianism in the 1970s was really much larger than that. It was really the “general equilibrium” revolution.

Macroeconomics until 1970 was sharply different from regular microeconomics. Economics is all about “models,” complete toy economies that we construct via equations and in computer programs. You can’t keep track of everything in even the most beautiful prose. Microeconomic models, and “general equilibrium” as that term was used at the time, wrote down how people behave — how they decide what to buy, how hard to work, whether to save, etc.. Then it similarly described how companies behave and how government behaves. Set this in motion and see where it all settles down; what prices and quantities result.

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

Hoover Monetary Policy Conference

Friday May 12 we had the annual Hoover monetary policy conference. Hoover twitter stream here. Conference webpage and schedule here (update 5/24 now contains videos.) As before, the talks, panels, and comments will eventually be written and published.

The Fed has experienced two dramatic institutional failures: Inflation peaking at 8%, and a rash of bank failures. There were panels focused on each, and much surrounding discussion.

Monday, May 15, 2023

Bob Lucas

I just got the sad news that Bob Lucas has passed away. He was truly a giant among economists, and a wonderful warm person.

I will only pass on three remembrances that others will not likely mention.

Bob was incredibly welcoming to me, a young brash and fairly untutored young economist from Berkeley.

In the fall of 1985 I gave what was no doubt the most disastrous first seminar by a new assistant professor in the Department's history. It was something about random walks and real business cycles, and was going nowhere. Bob stopped by my office, and expressed doubt about this random walk stuff. He said, if you look at longer and longer horizons, GNP volatility goes down. At least I had the wit to recognize what had just been handed to me on a silver platter, dropped everything and wrote the "Random walk in GNP," my first big paper. Without that, I doubt I would be where I am today. Thank you Bob. He and Nancy were kind to us socially as well.

The first Lucas paper that I recall reading, while I was still at Berkeley, was his review of a report to the OECD. I don't think anyone else writing about Bob will mention this masterpiece. If you get annoyed by policy blather, read this article. Reading it as a grad student, I loved the way he sliced through loose prose like warm butter. No BS with Bob. Only clear thinking please. I mentioned it later, and he laughed saying he wrote it in a bad mood because he was getting divorced. Like "After Keynesian Macroeconomics," Bob could wield a pen.

Much later, I attended a revelatory money workshop. Bob presented an early version of, I think, "Ideas and growth." In the model, people have ideas, and bump into each other randomly and share ideas. Questioner after questioner complained that there wasn't any economics in the model. Why not put in some incentive for people to bump in to each other, or something non mechanical. Time after time, Bob answered each suggestion that he had tried it, but it didn't make much difference to the outcome, so he stripped it out of the model. Clearly, he had been playing with this model over a year, working to eliminate needless ingredients, not to add more generality. It's great to see the production function at work.

Bob is known as a theorist, but he had a great handle on empirical work as well. His Carnegie Rochester money demand paper basically reinvented cointegration, and saw clearly what dozens of others missed. "Mechanics of economic development" starts by putting together facts. "International evidence on inflation-output tradeoffs" 1973 makes one stunning graph. And more.

There is so much to say about Bob the great economist, superb colleague and tremendous human being, but I will stop here for now. RIP Bob. And thank you.

Update:

Ben Moll has a lovely twitter thread about Bob as a thesis adviser. Bob covered Ben's thesis draft with useful comments. Bob read my early papers and did the same thing. This encouraged a culture of comments. Though a young assistant professor, I took it as a duty to write comments on Bob's papers! And some of them actually helped. This was the culture of the economics department in the 1980s, not common. Bob helped quite a few people and JPE authors to see what their papers were really about, making dramatic improvements.

The outpouring on twitter is remarkable. More remarkable, here is a man for whom we could celebrate every single paper as pathbreaking. Yet the outpouring is all about his wonderful personal qualities.

A correspondent reminds me of one last story. Bob's divorce agreement specified half of his Nobel prize, which he paid. Asked by a reporter if he had regrets, he answered "A deal's a deal."

Next post, focused on intellectual contributions.

FTPL 50% off sale

Princeton University Press has a 50% off sale on all books, including the (overpriced, sorry) Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. The splash page also offers 30% off if you give them your email, but I'm not sure if they add.

Saturday, May 13, 2023

Missing mortgage contract innovation

From WSJ

"Many Americans who want to move are trapped in their homes—locked in by low interest rates they can’t afford to give up.

These “golden handcuffs” are keeping the supply of homes for sale unusually low and making the market more competitive and pricey than some forecasters expected.

The reluctance of homeowners to sell differentiates the current housing market from past downturns and could keep home prices from falling significantly on a national basis, economists say."

What's going on? US 15 or 30 year fixed-rate mortgages have a catch -- you can't take it with you. If interest rates go up, and you want to move, you can't take the old mortgage with you. You have to refinance at the higher interest rate. It's curiously asymmetric, as if interest rates go down you have the right to refinance at a lower rate.

As a result, yes, people stay in houses they would rather sell in order to keep the low interest rate on their fixed rate mortgage. They then don't free up houses that someone else would really rather buy. (In California, the right to keep paying low property taxes, which reset if you buy a new house also keeps some people where they are. And everywhere, transfer taxes add a small disincentive to move.)

This is a curious contract structure. Why can't you take a mortgage with you, and use it to pay for a new house? Sure, mortgages with that right would cost more; the rate would be a bit higher initially. But fixed rate mortgages already cost more than variable rate mortgages, and people seem willing to pay for insurance against rising rates. I can imagine that plenty of people might want to buy that insurance to make sure they can live in a house of given cost, though not necessarily this house. Conversely, fixed-rate mortgages that did not give the right to refinance, where you have to pay a penalty to get out of the contract if rates go down, would also be cheaper up front, yet people aren't screaming for those.

Thursday, April 20, 2023

How do interest rates lower inflation?

A few days ago I gave a short talk on the subject. I was partly inspired by a little comment made at a seminar, roughly "of course we all know that if prices are sticky, higher nominal rates raise higher real rates, that lowers aggregate demand and lowers inflation." Maybe we "know" that, but it's not as readily present in our models as we think. This also crystallizes some work in the ongoing "Expectations and the neutrality of interest rates" project.

The equations are the utterly standard new-Keynesian model. The last equation tracks the evolution of the real value of the debt, which is usually in the footnotes of that model.

OK, top right, the standard result. There is a positive but temporary shock to the monetary policy rule, u. Interest rates go up and then slowly revert. Inflation goes down. Hooray. (Output also goes down, as the Phillips Curve insists.)

The next graph should give you pause on just how you interpreted the first one. What if the interest rate goes up persistently? Inflation rises, suddenly and completely matching the rise in interest rate! Yet prices are quite sticky -- k = 0.1 here. Here I drove the persistence all the way to 1, but that's not crucial. With any persistence above 0.75, higher interest rates give rise to higher inflation.

What's going on? Prices are sticky, but inflation is not sticky. In the Calvo model only a few firms can change price in any instant, but they change by a large amount, so the rate of inflation can jump up instantly just as it does. I think a lot of intuition wants inflation to be sticky, so that inflation can slowly pick up after a shock. That's how it seems to work in the world, but sticky prices do not deliver that result. Hence, the real interest rate doesn't change at all in response to this persistent rise in nominal interest rates. Now maybe inflation is sticky, costs apply to the derivative not the level, but absolutely none of the immense literature on price stickiness considers that possibility or how in the world it might be true, at least as far as I know. Let me know if I'm wrong. At a minimum, I hope I have started to undermine your faith that we all have easy textbook models in which higher interest rates reliably lower inflation.

(Yes, the shock is negative. Look at the Taylor rule. This happens a lot in these models, another reason you might worry. The shock can go in a different direction from observed interest rates.)

Panel 3 lowers the persistence of the shock to a cleverly chosen 0.75. Now (with sigma=1, kappa=0.1, phi= 1.2), inflation now moves with no change in interest rate at all. The Fed merely announces the shock and inflation jumps all on its own. I call this "equilibrium selection policy" or "open mouth policy." You can regard this as a feature or a bug. If you believe this model, the Fed can move inflation just by making speeches! You can regard this as powerful "forward guidance." Or you can regard it as nuts. In any case, if you thought that the Fed's mechanism for lowering inflation is to raise nominal interest rates, inflation is sticky, real rates rise, output falls and inflation falls, well here is another case in which the standard model says something else entirely.

Panel 4 is of course my main hobby horse these days. I tee up the question in Panel 1 with the red line. In that panel, the nominal interest are is higher than the expected inflation rate. The real interest rate is positive. The costs of servicing the debt have risen. That's a serious effect nowadays. With 100% debt/GDP each 1% higher real rate is 1% of GDP more deficit, $250 billion dollars per year. Somebody has to pay that sooner or later. This "monetary policy" comes with a fiscal tightening. You'll see that in the footnotes of good new-Keynesian models: lump sum taxes come along to pay higher interest costs on the debt.

Now imagine Jay Powell comes knocking to Congress in the middle of a knock-down drag-out fight over spending and the debt limit, and says "oh, we're going to raise rates 4 percentage points. We need you to raise taxes or cut spending by $1 trillion to pay those extra interest costs on the debt." A laugh might be the polite answer.

So, in the last graph, I ask, what happens if the Fed raises interest rates and fiscal policy refuses to raise taxes or cut spending? In the new-Keynesian model there is not a 1-1 mapping between the shock (u) process and interest rates. Many different u produce the same i. So, I ask the model, "choose a u process that produces exactly the same interest rate as in the top left panel, but needs no additional fiscal surpluses." Declines in interest costs of the debt (inflation above interest rates) and devaluation of debt by period 1 inflation must match rises in interest costs on the debt (inflation below interest rates). The bottom right panel gives the answer to this question.

Review: Same interest rate, no fiscal help? Inflation rises. In this very standard new-Keynesian model, higher interest rates without a concurrent fiscal tightening raise inflation, immediately and persistently.

Fans will know of the long-term debt extension that solves this problem, and I've plugged that solution before (see the "Expectations" paper above).

The point today: The statement that we have easy simple well understood textbook models, that capture the standard intuition -- higher nominal rates with sticky prices mean higher real rates, those lower output and lower inflation -- is simply not true. The standard model behaves very differently than you think it does. It's amazing how after 30 years of playing with these simple equations, verbal intuition and the equations remain so far apart.

The last two bullet points emphasize two other aspects of the intuition vs model separation. Notice that even in the top left graph, higher interest rates (and lower output) come with rising inflation. At best the higher rate causes a sudden jump down in inflation -- prices, not inflation, are sticky even in the top left graph -- but then inflation steadily rises. Not even in the top left graph do higher rates send future inflation lower than current inflation. Widespread intuition goes the other way.

In all this theorizing, the Phillips Curve strikes me as the weak link. The Fed and common intuition make the Phillips Curve causal: higher rates cause lower output cause lower inflation. The original Phillips Curve was just a correlation, and Lucas 1972 thought of causality the other way: higher inflation fools people temporarily to producing more.

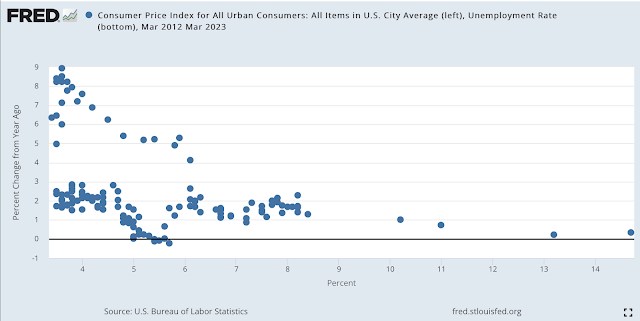

Here is the Phillips curve (unemployment x axis, inflation y axis) from 2012 through last month. The dots on the lower branch are the pre-covid curve, "flat" as common wisdom proclaimed. Inflation was still 2% with unemployment 3.5% on the eve of the pandemic. The upper branch is the more recent experience.

I think this plot makes some sense of the Fed's colossal failure to see inflation coming, or to perceive it once the dragon was inside the outer wall and breathing fire at the inner gate. If you believe in a Phillips Curve, causal from unemployment (or "labor market conditions") to inflation, and you last saw 3.5% unemployment with 2% inflation in February 2021, the 6% unemployment of March 2021 is going to make you totally ignore any inflation blips that come along. Surely, until we get well past 3.5% unemployment again, there's nothing to worry about. Well, that was wrong. The curve "shifted" if there is a curve at all.

But what to put in its place? Good question.

Update:

Lots of commenters and correspondents want other Phillips Curves. I've been influenced by a number of papers, especially "New Pricing Models, Same Old Phillips Curves?" by Adrien Auclert, Rodolfo Rigato, Matthew Rognlie, and Ludwig Straub, and "Price Rigidity: Microeconomic Evidence and Macroeconomic Implications" by Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson, that lots of different micro foundations all end up looking about the same. Both are great papers. Adding lags seems easy, but it's not that simple unless you overturn the forward looking eigenvalues of the system; "Expectations and the neutrality of interest rates" goes on in that way. Adding a lag without changing the system eigenvalue doesn't work.

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

On marking to market and risk management

Two more thoughts:

1) In the SBV debacle, many of my colleagues and friends jump to the conclusion, we should just mark all assets to market and forget about this "hold to maturity" business.

Not so fast. Like all imperfect patches, there is some logic to it. Suppose you have a $100 payment that you have to make in 10 years. To cover that payment, you buy a $100 face value Treasury zero coupon bond. Done, zero risk.

Now interest rates rise. The value of your asset has fallen in value! It's only worth, say, $90! Are you underwater? No, because when the time comes, you still will have exactly $100 to make the needed payment.

You will quickly answer, well, mark both assets and liabilities to market. The $100 payment is now also worth $90, so marking both sides to market would reveal no change. But there is a lot of unneeded volatility here. And in most cases, the $100 payment is not tradeable on a market, while the $100 asset is. So now, you're going to be balancing marking to market vs. marking to model. Add the regulator's and many participant's distrust of market prices, which are always seemingly "illiquid," "distressed," in a state of "fire sale," "dysfunctional," and so forth. Add the pointlessness of it all. In this situation we all know that you can make the payment in 10 years. Lock it up and ignore it. Call the asset "hold to maturity."

Of course, suppose the point of that asset is to make sure that depositors with $100 accounts can always get their money back by selling the asset. Well, now we have Silicon Valley Bank.

Hence the imperfect fudge of current accounting and regulation rules. "Hold to maturity" assets don't get marked to market, and indeed there are penalties for selling them to meet current needs. Lots of "liquidity" and other rules are supposed to make sure there are adequate short run liabilities to stop a run. Those were of course completely absent in SBV's case -- a truly spectacular failure of elementary regulation.

In short, mark to market makes sense to assess if a bank can make its payments and avoid failure tomorrow. Hold to maturity makes a bit of sense to assess if a bank can make its payments and avoid failure years from now, when both long term assets and long term liabilities come due. That is, if it survives that long.

2) There is a lot of criticism of SBV bank management and board for being underinvested in risk management and over invested in lobbying, political connections, donations to politically popular causes, and so forth. Ex post, their choice of managerial investments looks brilliant! What brought in the millions to stem a run, I ask you? In today's highly political banking system, they made optimal choices. To an economist, many puzzling actions are just an optimal answer to a different question.

Update: Ok, I went too far with that one. Management are out, shareholders wiped out. I'll stick with the idea that uninsured depositors did a great job of monitoring -- they monitored that the bank had the political chops to demand and get a bailout of uninsured depositors!

From a correspondent:

"It seems to me now that SVB was really a money market fund with the addition of a bit of equity and breaking all the SEC asset and liquidity rules that MMFs are subject to. "

Or, it was really a mutual fund (money market funds with $1 values can't invest in long term bonds, long term bond funds must have floating NAV) that was violating rules on floating NAV!

Small bank thoughts

Three small thoughts.

1) There is much commentary that bank troubles will interfere with the Fed's plan to lower inflation by raising rates. Actually, this is a feature not a bug. The main mechanism by which, in the Fed's view, raising interest rates slows the economy and lowers inflation is by "constricting credit," "tightening financial conditions," lowering borrowing that finances investment and consumer durables purchases. The Fed didn't want runs, no, but it wants the result. If you don't like that, well, we need to think of other ways to contain inflation, like taking the fiscal gasoline off the fire.

2) On uninsured deposits. A correspondent suggests that the Fed simply mandate that all large depositors participate in the sorts of services, there for the asking, that split large accounts into multiple $249k accounts spread over multiple banks, or sweeps into money market funds.

I don't think that mandating this system is a good idea. If you're going to do that, of course, you might as well just insure all deposits and keep it simple.

But the suggestion prompts doubt over the oft repeated notion that we want large sophisticated depositors to monitor banks. Anyone who was large and sophisticated enough to monitor banks had already gamed the system to make sure their accounts were insured, at some nontrivial cost in fees and trouble. The only people left with millions in checking accounts were, sort of by definition, financially unsophisticated or too busy running actual companies to bother with this sort of thing. Sort of like taxes.

We might as well give in, that all deposits are here forth insured. If so, of course, then banks are totally gambling with the house's money. But we also have to give in that if they can't spot this elephant in the room, asset risk regulation is hopeless. The only workable answer (of course) is narrow deposit taking -- all runnable deposits invested in reserves and short term treasuries; fund portfolios of long term debt with long-term borrowing (CDs for example) and lots of equity.

3) Liquidity and fixed value are no longer necessarily tied together. I still don't quite get why better payment services are not attached to floating value funds. Then we wouldn't need run-prone bank accounts at all.

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

How many banks are in danger?

With amazing speed and impeccable timing, Erica Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru analyze how exposed the rest of the banking system is to an interest rate rise.

Recap: SVB failed, basically, because it funded a portfolio of long-term bonds and loans with run-prone uninsured deposits. Interest rates rose, the market value of the assets fell below the value of the deposits. When people wanted their money back, the bank would have to sell at low prices, and there would not be enough for everyone. Depositors ran to be the first to get their money out. In my previous post, I expressed astonishment that the immense bank regulatory apparatus did not notice this huge and elementary risk. It takes putting 2+2 together: lots of uninsured deposits, big interest rate risk exposure. But 2+2=4 is not advanced math.

How widespread is this issue? And how widespread is the regulatory failure? One would think, as you put on the parachute before jumping out of a plane, that the Fed would have checked that raising interest rates to combat inflation would not tank lots of banks.

Banks are allowed to report the "hold to maturity" "book value" or face value of long term assets. If a bank bought a bond for $100 (book value) or if a bond promises $100 in 10 years (hold to maturity value), basically, the bank may say it's worth $100, even though the bank might only be able to sell the bond for $75 if they need to stop a run. So one way to put the issue is, how much lower are mark to market values than book values?

The paper (abstract):

The U.S. banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity. Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%.

... 10 percent of banks have larger unrecognized losses than those at SVB. Nor was SVB the worst capitalized bank, with 10 percent of banks have lower capitalization than SVB. On the other hand, SVB had a disproportional share of uninsured funding: only 1 percent of banks had higher uninsured leverage.

... Even if only half of uninsured depositors decide to withdraw, almost 190 banks are at a potential risk of impairment to insured depositors, with potentially $300 billion of insured deposits at risk. ... these calculations suggests that recent declines in bank asset values very significantly increased the fragility of the US banking system to uninsured depositor runs.