Now that 30 days have passed, I can post the full text of "Nobody Knows How Interest Rates Affect Inflation" in the Wall Street Journal August 25. A previous post has a summary with pretty pictures.

***

A grand economic experiment is under way. Can the Federal Reserve contain inflation without raising interest rates much higher than they are now?

Conventional wisdom says that as long as interest rates are below the rate of inflation, inflation will rise. Inflation in July was 8.5%, measured as the one-year change in the consumer price index. The Fed has raised the federal funds rate only from 0.08% in March to 2.33% in August. According to the conventional view, that isn’t nearly enough. Higher rates are needed, now.

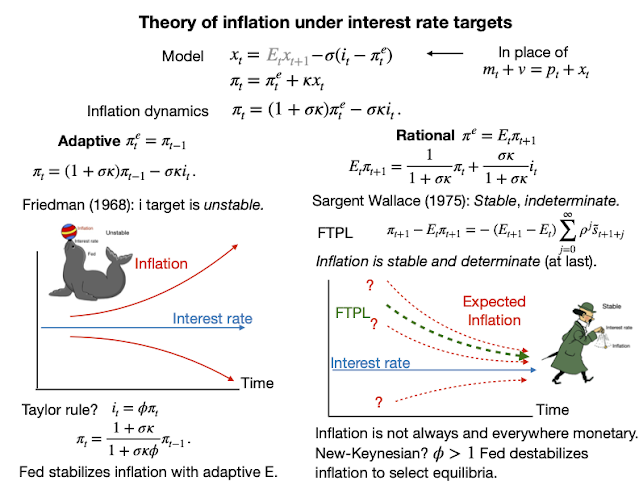

This conventional view holds that the economy is inherently unstable. The Fed is like a seal, balancing a ball (inflation) on its nose (interest rates). To keep the ball from falling, the seal must quickly move its nose.

In a newer view, the economy is stable, like a pendulum. Even if the Fed does nothing, so long as there are no more shocks, inflation will eventually peter out. The Fed can reduce inflation by raising interest rates, but interest rates need not exceed inflation to prevent an inflationary spiral. This newer view is reflected in most economic models of recent decades. It accounts for the Fed’s projections and explains the Fed’s sluggish response. Stock and bond markets also foresee inflation fading away without large interest-rate rises.

So which view is correct? In normal times, it’s hard to tell. Whether seal or pendulum, inflation and interest rates move up or down together in the long run, and they jiggle around each other in the short run.

Advocates for the conventional view argue that the Fed raised interest rates too little in response to inflationary shocks in the 1970s. Only when the Fed raised interest rates substantially above inflation for several years in the early 1980s, provoking two deep recessions, did inflation finally subside. The sooner we get to it, they say, the better.

Advocates for the stable view point to recent decades of steady inflation at zero interest rates in the U.S., Europe and Japan. When deflation appeared and central banks couldn’t move rates much below zero, conventional analysts warned of a “deflation spiral.” It never happened. Why should an inflation spiral break out now?

In both theories, expected inflation matters: If people expect higher inflation next year, they buy or raise prices today. The central assumption behind the unstable inflation-spiral theory is that people expect next year’s inflation to be pretty much the same as last year’s inflation—what economists call “adaptive expectations.” A driver who looks in the rearview mirror to judge where the road is will quickly veer off to one side or another.

The central assumption behind the stable theory is that people think more broadly about future inflation. They’re not clairvoyant, but they don’t ignore useful information and aren’t much worse at forecasting inflation than, say, Fed economists are. If a driver looks forward through the windshield, even a dirty windshield, the car tends to get back on the road.

Economists don’t know for sure whether the economy is stable or unstable, whether inflation can fade away without interest rates substantially above inflation. In that light, the Fed’s actions make some sense. If you really don’t know how interest rates affect inflation, it’s natural to raise rates slowly. Inflation may subside on its own. If not, you can keep raising rates.

If inflation fades, the conventional view will be seriously undermined. If it spirals, absent other shocks, the new view is in trouble. But a good experiment requires everyone to leave the test tube alone. Unfortunately, we are likely to see some new shock: a virus, a war, a financial crisis or a fiscal blowout. Inflation will then rise or fall for reasons having nothing to do with spirals, stability and interest rates.

Mr. Cochrane is a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution and an adjunct scholar of the Cato Institute. His book “The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level” is out in January.

Update:

Economists wondering what the heck I'm talking about and where are the equations should read "Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest rates."