This is another post from an Economic Policy Working Group meeting at Hoover, in which simple undergraduate supply and demand analysis, creatively applied, leads to a surprising result.

Casey Mulligan presented "Prices and Policies in Opioid Markets." Paper, slides and video of the presentation. (Updated link now works)

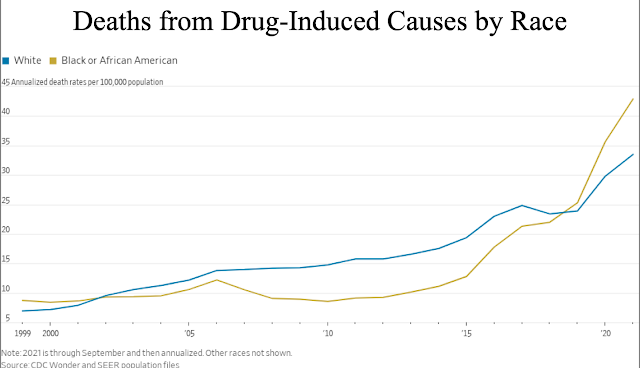

Once prescription opioids became an evident crisis, the government took steps to restrict the supply, raising the price. Yet opioid consumption and overdoses went up. Explain that Mr. Chicago economist!

Here's the clever answer:

There are two ways to buy opioids, 1) legally or semi-legally; i.e. get opioids that come from pharmaceutical companies and are prescribed to someone by a doctor or 2) illegally."In the earlier years, opioid subsidies are created and expanded for patients and prescribers while regulations are relaxed. In about 2010 policies begin to swing in the other direction as the with reformulation (see below) and programs discouraging prescription supply to secondary markets. ... enforcement of illicit-drug prohibitions was less of a priority between 2013 and 2016.

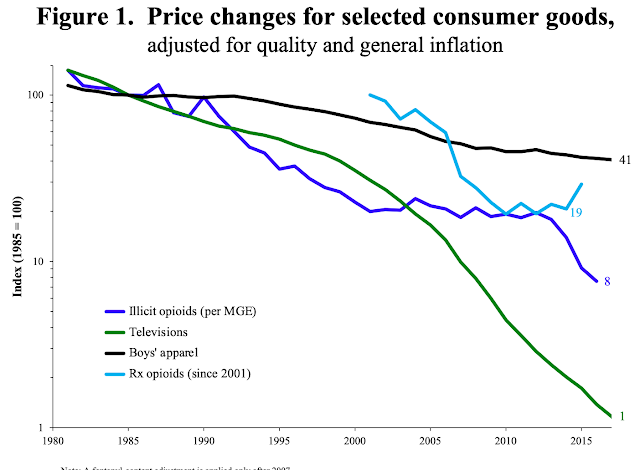

(i) heroin was significantly more expensive per MGE than Rx opioids in the 1990s, (ii) illicit opioids became cheaper over time, especially since 2013, and ultimately cheaper than Rx opioids, and (iii) beginning in about 2011, Rx opioids became more expensive or difficult to access for nonmedical use due to regulatory and fiscal changes.

The tide of needle litter came in heavy at the start of every month, when benefit checks arrived and people were briefly flush. .... There were far fewer by month’s end, but when the first of the month came again, a fresh swell always followed.

Michael Shellenberger thought to ask the question, receiving a different and even more uncomfortable answer, theft, though also benefits here.

Don't jump from these observations to a policy conclusion, which is not my point. I don't have an easy solution to the combination of drugs and homelessness. But following the money is surely a question that needs to be asked if we wish to understand the forces behind widespread addiction, and the externalities that drug users create. This might be a case in which paternalism is justified, and cash benefits not such a good idea.

Meanwhile, drug use is apparently way down in Afghanistan, by methods that we would not want to use, but an interesting fact (and an absorbing report) as well.

Where do the illegall drugs come from? Obviously they are from black market suppliiers, who are in the business to compete under the high-priced umbrella of the legal producers. But will they not compete against themselves and be forced to lower their prices. Not a part of the scenario, consider: 1. Black market products are not alll the same quality. 2, In order to compete on price, they need to find means of reducing costs, and 3. Furthermore the black market competitor does not maintain a consistent strength of his product. 4. The user, trying to increase the "high" may be more liikely to overdose.

ReplyDeleteGeralldgruber

Stripping models down is effective and used by physicists all the time in explaining how a law works before bringing in forces like friction. The use of 'thought experiments' was very important during the revolutions of relativity and quantum mechanics to illustrate some of the more bizarre behaviour of particles ...

ReplyDeleteIn the 6th paragraph, "If the user stayed with legal drugs, he or she would use less." This statement would be true iff the patient consumed the same amount of other goods/services. If the patient reduced his/her consumption of other goods/services the amount of Rx opiods consumed would be unchanged. The patient would be on a different "indifference curve", true, but the consumption of Rx opiods would be unchanged.

ReplyDeleteThe red lines and the black line are often referred to as "budget lines". The blue convex curve is an indifference curve, of which there are many typically nested with the higher curves representing higher utility. The patient's basket of goods/services would move from B to C if the individual was maximizing short-term utility. Instead, if the move was vertically downward from B (along the vertical line representing constant opiod consumption, say, X) to the intersection with the new Rx budget line, the reduction in the consumption of "all other goods" (say, Y) would be minimal compared to the reduction in the consumption of "all other goods" represented by the basket labelled C, and the switching cost ("black market fixed cost") would not be incurred. In this case, the decrease in utility (the move to a lower indifference curve) would appear to be the prudent course of action.

Fentanyl cut with heroin or cocaine (for the euphoria effect) by the Im producer or distributor, possibly containing impurities such as strychnine, will lead to increasing habituation locking the user into the dealers' customer base as long as the user lives and the user's income can support the habit. From the user of Im substances point of view, the "black market fixed cost" includes all of the collateral costs around degradation of lifestyle, income earning capacity, and untimely death, not solely the 'cost' of getting over the fear of needles and/or 'scoring' in the illegal drug street scene.

Ultimately it is up to the individual to decide on the course to take. Education would do some good. Interdiction would raise the marginal cost of the Im product, but the likelihood of making a large indent in the supply of fentanyl (produced in the PRC) is low. Reducing the price of Rx opiods would move B to a higher indifference curve (high utility) and change the mix of X and Y, but also cause the Im producers to lower their street price (the black budget line rotates upward around the intersection (pivot point) on the Y-axis). There may be no solution to the problem. Those who are susceptible to habituation will have to take their chances and bear the cost if they cannot constrain their usage.

The explanation is economic; the problem is rooted in sociology and pharmacology.

I looked at the whole talk. Really, really good and deep. Some of the comments weren't cool.

ReplyDeleteHow do drug users get money for drugs? Credit. My best friend and I used meth in high school. He got addicted. I didn't. He didn't have a job. He was a teenager. He would get an eight ball on credit, payment due in two days on pain of death. He'd break it up into lines, sell to casual users at a good markup, pay back the next day. Good credit, good reputation, just like any other business. He'd keep this going with his addiction fed by cash from casual users. It was easy. He'd run out of meth before he'd run out of money (three or four days of being awake and doing this and everything that had been in town would be distributed fully between addicts and casual users). Then he'd have to sleep and would have a small profit. It's actually pretty easy.

ReplyDeleteAnother way to flush this out is with basic consumer theory where MRT = MRS: two drugs, one legal one not, and they do the same thing, (simple utility function - perfect substitutes) but cost different amounts where legal(p) > illegal(p).Raise prices a few times watch the change in optimal bundles based on BC. Corner solutions.

ReplyDeleteThe vast majority of drug users are never homeless. A solid majority of homeless people are not addicted to drugs. By far the majority of opiate users never use needles. The fixed cost discussed is assumed to be higher for illegal drugs than prescribed drugs until the opposite assumption is suddenly made for black people. I think this analysis doesn't engage well with reality.

ReplyDeleteThese two 'reasonable assumptions' should be the subject of some data analysis in the future.

ReplyDeleteThe links to the paper and slides is broken at Hoover now.

ReplyDelete