Steve (and Nick Bloom) have done a great job quantifying policy uncertainty over time. To be clear, policies can have two effects -- there is the certainty of damaging policy, but there is also the damaging uncertainty of what policy will be. If a trade war seems to be looming, and you don't know if you will get tariff protection (raw steel) or be hurt by the tariff (steel users, competing with tariff-free steel products from abroad), that's uncertainty. Businesses hold off investing when they know things will be bad. But they also hold off when they're not sure what will happen. That's uncertainty.

Our little (so far) trade war is full of uncertainty

Trade policy under the Trump administration also has a capricious, back-and-forth character... Less than three months after withdrawing from the TPP, the President said he would consider rejoining for a substantially better deal, only to throw cold water on the idea a few days later. Initially, the administration justified steel tariffs on the laughable grounds that Canada, for example, presents a national security threat. Later, President Trump tweeted that tariffs on Canadian steel were a response to its tariffs on dairy products. Some countries get tariff exemptions, some don’t. Exemptions vary in duration, and they come and go in a head-spinning manner. Two days ago (August 10), the President tweeted that he “just authorized a doubling of Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum with respect to Turkey” for reasons unclear. For a fuller account of tariff to-ing and fro-ing under the Trump administration, see the Peterson Institute’s “Trump Trade War Timeline.”The arbitrariness, including the waivers, means

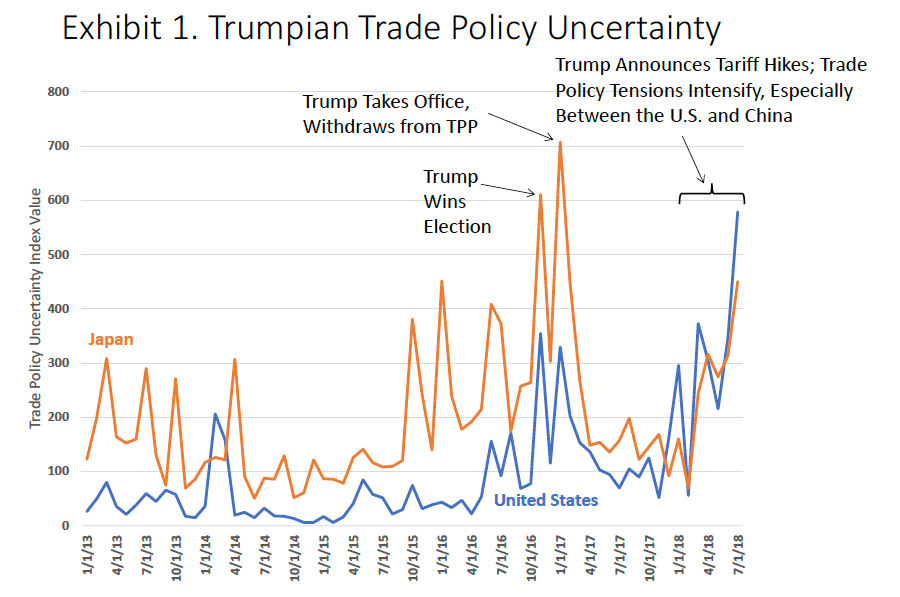

Crony capitalism, political favoritism, and extra sand in the gears of commerce – here we come!But to the point, what's the Davis-Bloom quantitative measure of uncertainty doing? Answer: it is higher than even around the election -- whose outcome, and the nature of the Trump presidency certainly led to a vast amount of uncertainty.

As of July, this uncertainty is only having a small effect on investment, and the economy is still booming -- in my view from the corporate tax rate cuts and deregulation efforts. It is true that the US is so big that most of the economy does not live on exports or directly compete with imports.

Let’s sum up the U.S. survey evidence: About one-fifth of firms in the July 2018 SBU say they are reassessing capital expenditure plans in light of tariff worries. Among this one-fifth, firms have reassessed an average 60 percent of capital expenditures previously planned for 2018–19. ..Only 6 percent of the firms in our full sample report cutting or deferring previously planned capital expenditures in reaction to tariff worries. These findings suggest that tariff worries have had only a small negative effect on U.S. business investment to date.But it could get worse. Steve closes with a nice list of recent trade outbursts from our part of the economics blog world:

In closing, I should note that the harmful consequences of tariff hikes and trade policy uncertainty extend well beyond short-term investment effects. For other critiques of the Trumpian approach to trade policy, see the worthy commentaries by Robert Barro, Alan Blinder, John Cochrane, Doug Irwin, Mary Lovely and Yang Liang, Greg Mankiw and Adam Posen, among others.

Nice post.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, China and Singapore provide free land and capital to export industries in a manner that it appears capricious, by free-market standards.

Europe subsidizes exports by not placing a VAT on exported goods.

At any time the subsidies to in those nations could be increased.

Obviously the level of and unpredictability of export subsidies around the world would make investing in the US highly uncertain.

Speaking of old Smoot and Hawley, see:

ReplyDeletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smoot–Hawley_Tariff_Act#/media/File:Average_Tariff_Rates_in_USA_(1821-2016).png

Average tariff rates across all imported goods modestly rose from a 100 year low of 5% in 1919 to 20% in 1933 as a result of Smoot Hawley. Prior to 1919, average tariff rates across all imported goods had been significantly higher dating back to the 1820's (peaking at almost 60% in 1830).

The big increase brought about by the Smoot Hawley bill was on dutiable imports (only those imported goods that a tariff is assessed on) rising from about 15% in 1920 to almost 60% in 1933.

Finally, the increase in Tariffs from 1920 to 1933 occurred in stages - the first of which was the lesser known and quoted Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fordney–McCumber_Tariff

Smoot Hawley was a an increase in Tariff rates above and beyond those prescribed in the Fordney-McCumber Act.

John,

Delete"In closing, I should note that the harmful consequences of tariff hikes and trade policy uncertainty extend well beyond short-term investment effects."

If Trump increased tariffs on top of what has already been implemented - similar to what Smoot and Hawley did after Fordney and McCumber, would that ease your and Steve's uncertainty concerns?

On how uncertainty impacts investment...

ReplyDelete"Imagine you are a company producing goods (in any country), thinking about adding a second manufacturing facility. But, rumors abound that your goods will face tariffs. Guess what? You are not going to build that second facility. How about the same type of company in the U.S.? Maybe they think business will improve with better trade protection. But what happens when Trump goes, or if he changes his mind on tariffs? Either way, that new facility is unlikely to get the green light to be built." —Financial Post

"...the administration justified steel tariffs on the laughable grounds that Canada, for example, presents a national security threat."

Trump was willing to remove those steel tariffs in exchange for Canada removing tariffs on dairy.

If Trump hadn't pulled out of the TPP, that's exactly what he would have got.

Delete