The Revenge of Supply, at Project Syndicate

Surging inflation, skyrocketing energy prices, production bottlenecks, shortages, plumbers who won’t return your calls – economic orthodoxy has just run smack into a wall of reality called “supply.”

Demand matters too, of course. If people wanted to buy half as much as they do, today’s bottlenecks and shortages would not be happening. But the US Federal Reserve and Treasury have printed trillions of new dollars and sent checks to just about every American. Inflation should not have been terribly hard to foresee; and yet it has caught the Fed completely by surprise.

The Fed’s excuse is that the supply shocks are transient symptoms of pent-up demand. But the Fed’s job is – or at least should be – to calibrate how much supply the economy can offer, and then adjust demand to that level and no more. Being surprised by a supply issue is like the Army being surprised by an invasion.

The current crunch should change ideas. Renewed respect may come to the real-business-cycle school, which focuses precisely on supply constraints and warns against death by a thousand cuts from supply inefficiencies. Arthur Laffer, whose eponymous curve announced that lower marginal tax rates stimulate growth, ought to be chuckling at the record-breaking revenues that corporate taxes are bringing in this year.

Equally, one hopes that we will hear no more from Modern Monetary Theory, whose proponents advocate that the government print money and send it to people. They proclaimed that inflation would not follow, because, as Stephanie Kelton puts it in The Deficit Myth, “there is always slack” in our economy. It is hard to ask for a clearer test.

But the US shouldn’t be in a supply crunch. Real (inflation-adjusted) per capita US GDP just barely passed its pre-pandemic level this last quarter, and overall employment is still five million below its previous peak. Why is the supply capacity of the US economy so low? Evidently, there is a lot of sand in the gears. Consequently, the economic-policy task has been upended – or, rather, reoriented to where it should have been all along: focused on reducing supply-side inefficiencies.

One underlying problem today is the intersection of labor shortages and Americans who are not even looking for jobs. Although there are more than ten million listed job openings – three million more than the pre-pandemic peak – only six million people are looking for work. All told, the number of people working or looking for work has fallen by three million, from a steady 63% of the working-age population to just 61.6%.

We know two things about human behavior: First, if people have more money, they work less. Lottery winners tend to quit their jobs. Second, if the rewards of working are greater, people work more. Our current policies offer a double whammy: more money, but much of it will be taken away if one works. Last summer, it became clear to everyone that people receiving more benefits while unemployed than they would earn from working would not return to the labor market. That problem remains with us and is getting worse.

Remember when commentators warned a few years ago that we would need to send basic-income checks to truck drivers whose jobs would soon be eliminated by artificial intelligence? Well, we started sending people checks, and now we are surprised to find that there is a truck driver shortage.

Practically every policy on the current agenda compounds this disincentive, adding to the supply constraints. Consider childcare as one tiny example among thousands. Childcare costs have been proclaimed the latest “crisis,” and the “Build Back Better” bill proposes a new open-ended entitlement. Yes, entitlement: “every family who applies for assistance … shall be offered child care assistance” no matter the cost.

The bill explodes costs and disincentives. It stipulates that childcare workers must be paid at least as much as elementary school teachers ($63,930), rather than the current average ($25,510). Providers must be licensed. Families pay a fixed and rising fraction of family income. If families earn more money, benefits are reduced. If a couple marries, they pay a higher rate, based on combined income. With payments proclaimed as a fraction of income and the government picking up the rest, either prices will explode or price controls must swiftly follow. Adding to the absurdity, the proposed legislation requires states to implement a “tiered system” of “quality,” but grants everyone the right to a top-tier placement. And this is just one tiny element of a huge bill.

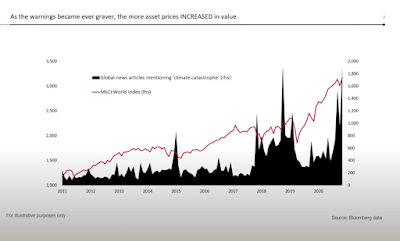

Or consider climate policy, which is heading for a rude awakening this winter. This, too, was foreseeable. The current policy focus is on killing off fossil-fuel supply before reliable alternatives are ready at scale. Quiz: If you reduce supply, do prices go up or go down? Europeans facing surging energy prices this fall have just found out.

In the United States, policymakers have devised a “whole-of-government” approach to strangle fossil fuels, while repeating the mantra that “climate risk” is threatening fossil-fuel companies with bankruptcy due to low prices. We shall see if the facts shame anyone here. Pleading for OPEC and Russia to open the spigots that we have closed will only go so far.

Last week, the International Energy Agency declared that current climate pledges will “create” 13 million new jobs, and that this figure would double in a “Net-Zero Scenario.” But we’re in a labor shortage. If you can’t hire truckers to unload ships, where are these 13 million new workers going to come from, and who is going to do the jobs that they were previously doing? Sooner or later, we have to realize it’s not 1933 anymore, and using more workers to provide the same energy is a cost, not a benefit.

It is time to unlock the supply shackles that our governments have created. Government policy prevents people from building more housing. Occupational licenses reduce supply. Labor legislation reduces supply and opportunity, for example, laws requiring that Uber drivers be categorized as employees rather than independent contractors. The infrastructure problem is not money, it is that law and regulation have made infrastructure absurdly expensive, if it can be built at all. Subways now cost more than a billion dollars per mile. Contracting rules, mandates to pay union wages, “buy American” provisions, and suits filed under environmental pretexts gum up the works and reduce supply. We bemoan a labor shortage, yet thousands of would-be immigrants are desperate to come to our shores to work, pay taxes, and get our economy going.

A supply crunch with inflation is a great wake-up call. Supply, and efficiency, must now top our economic-policy priorities.

*********

Update: I am vaguely aware of many regulations causing port bottlenecks, including union work rules, rules against trucks parking and idling, overtime rules, and so on. But it turns out a crucial bottleneck in the port of LA is... Zoning laws! By zoning law you're not allowed to stack empty containers more than two high, so there is nowhere to leave them but on the truck, which then can't take a full container. The tweet thread is really interesting for suggesting the ports are at a standstill, bottled up FUBARed and SNAFUed, not running full steam but just can't handle the goods.

Disclaimer: To my economist friends, yes, using the word "supply" here is not really accurate. "Aggregate supply" is different from the supply of an individual good. Supply of one good increases when its price rises relative to other prices. "Aggregate supply" is the supply of all goods when prices and wages rise together, a much trickier and different concept. What I mean, of course, is something like "the amount produced by the general equilibrium functioning of the economy, supply and demand, in the absence of whatever frictions we call low 'aggregate demand', but as reduced by taxes, regulations, and other market distortions." That being too much of a mouthful, and popular writing using the word "supply" and "supply-side" for this concept, I did not try to bend language towards something more accurate.