Project Syndicate asked Mike Boskin, Brigitte Granville, Ken Rogoff and me whether 2% is the right inflation target. See the link for the other views. I pretty much agree with them in the short run -- don't mess with it -- but took a different long run view. Apparently Volcker and Greenspan were fans of price level targeting and hoped to get there eventually, which is the sort of long run approach I took here.

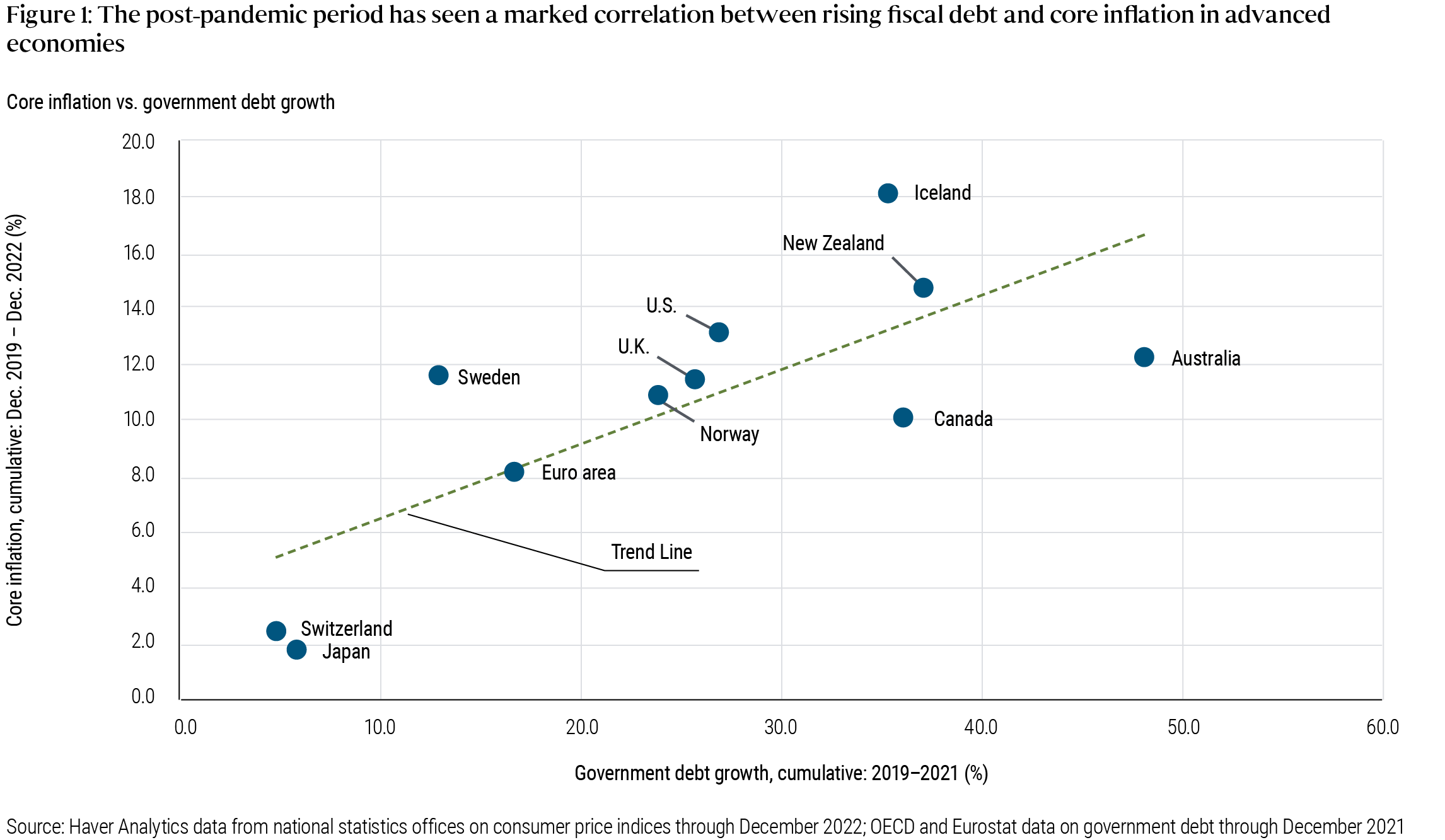

I also emphasize that any inflation target is (of course) a joint target of fiscal as well as monetary policy. Fiscal policy needs to commit to repay debt at the inflation target.

My view:

No, 2% is not the right target. Central banks and governments should target the price level. That means not just pursuing 0% inflation, but also, when inflation or deflation unexpectedly raise or lower the price level, gently bringing the price level back to its target. (I say “and governments” because inflation control depends on fiscal policy, too.)

The price level measures the value of money. We don’t shorten the meter 2% every year. Confidence in the long-run price level streamlines much economic, financial, and monetary activity. The corresponding low interest rates allow companies and banks to stay awash in liquidity at low cost. A commitment to repay debt without inflation also makes government borrowing easier in times of war, recession, or crisis.