On May 6 the annual Hoover monetary policy conference returned. It was great. In particular, the opening panels by Rich Clarida, Larry Summers, and John Taylor, and the final panel with Jim Bullard, Randy Quarles, and Christopher Waller were eloquent and insightful. Alas, the videos and transcripts aren't quite ready so you have to wait for all that. There will also be a conference volume putting it all together.

In the meantime, I wrote a paper for my short talk; and thanks to the Hoover team I also have a transcription of the talk. The paper is "Inflation Past, Present and Future: Fiscal Shocks, Fed Response, and Fiscal Limits." It pulls together ideas from a bunch of recent blog posts, other essays, bits and pieces of Fiscal Theory of the Price level. Sorry for the repetition, but repackaging and simplifying ideas is important. Here's the talk version, shorter but with less nuance:

Inflation Past, Present and Future: Fiscal Shocks, Fed Response, and Fiscal Limits

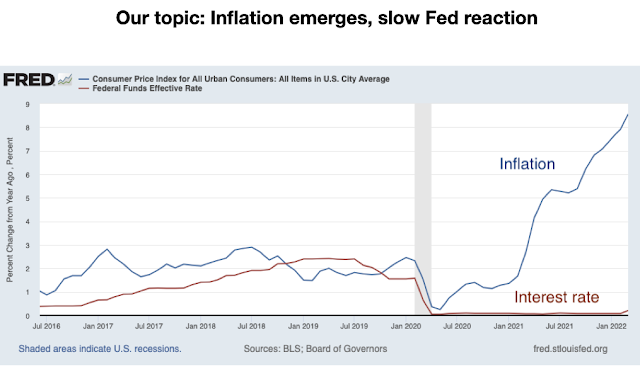

Here we are. Inflation has emerged, and the Fed is reacting rather slowly.

Why? Where did inflation come from, is question number one, and Charlie Plosser gave away the answer in his nice preface to this session: The government basically did a fiscal helicopter drop, five to six trillion dollars of money sent in a particularly powerful way. They sent people checks, half of it new reserves, half of it borrowed. It's a fiscal helicopter drop. Imagine that this had been simply $6 trillion of open market operations. Well, as Larry just told us, $6 trillion more $10 bills and $6 trillion fewer $100 bills won’t make much difference. If there had been no deficit, it certainly wouldn't have had such a huge effect.

The impulse was not the fault of interest rate policy either. Interest rates have just been flat. One can blame the Fed for contributing to the great helicopter drop, but not for a big interest rate shock.

So that's the inflationary impulse, but where is inflation going now? Now, attention turns to the Fed. Interest rates stayed flat while inflation got going from the fiscal shock, as you see in the first graph.

So the next question is, does this slow response; this period of nominal interest rates far below inflation, constitute additional monetary stimulus, which creates additional inflation on its own? Or are we simply waiting for the fiscal (or supply, if you must) shock to blow over?