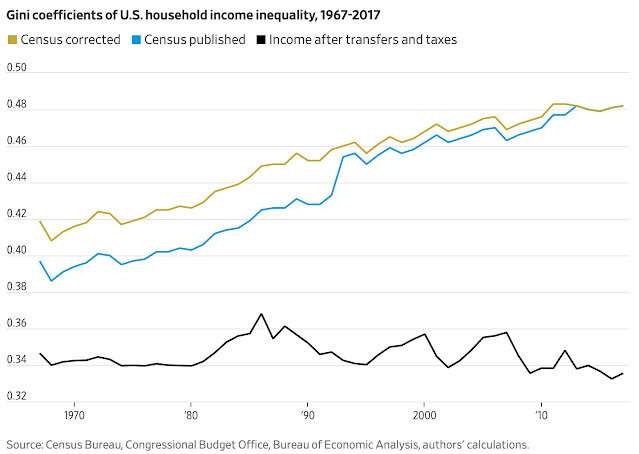

In one of their series of excellent WSJ essays, Phil Gramm and John Early notice that conventional income inequality numbers report the distribution of income before taxes and transfers. After taxes and transfers, income inequality is flat or decreasing, depending on your starting point.

|

| Source: Phil Gramm and John Early in the Wall Street Journal |

If your game is to argue for more taxes and transfers to fix income inequality, that is a dandy subterfuge as no amount of taxing and transferring can ever improve the measured problem!

Now facts are facts, and this one has a good progressive interpretation: But for our sharply progressive tax system and benefits, untrammeled capitalism would have led to sharply increased inequality. The numbers don't argue for more redistribution, but they are consistent with a narrative that only our current large redistribution saved us from the top two lines.

Gramm and Early offer a sentence on this worth pausing to think about:

As government transfer payments to low-income households exploded, their labor-force participation collapsed and the percentage of income in the bottom quintile coming from government payments rose above 90%.

A major force behind the pre-tax and pre-transfer numbers is the fall in labor force participation among people experiencing low income. It is not entirely impossible that some causality runs from larger means-tested benefits -- earn a dollar lose a dollar worth of benefits -- to withdrawing from the workforce, rather than the other way around.

The second clause is enlightening. People experiencing income in the bottom fifth of the US population get 90% of their income from the government.

There is lots more to unpack in distributional numbers of course. Household composition and demographics have changed, consumption inequality matters not income inequality, the relative prices of things people buy have diverged -- goods cheaper, services more expensive, cities and states like CA much more expensive, and so on. But that so much debate is based on so transparently flawed a number is worth remembering.

It's not easy by the way. As the tax code is deliberately complicated, so is the nature of transfers.

Census Bureau income data fail to count two-thirds of all government transfer payments—including Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps and some 100 other government transfer payments—as income to the recipients.

These include the earned-income tax credit, whose beneficiaries get a check from the Treasury; food stamps, which let beneficiaries buy food with government issued debit cards; and numerous other programs in which government pays for the benefits directly.

I have not dug into the methods. How do you count services provided like housing, medical care, VA care, etc.?

Handy numbers, in addition to the 90% above:

In 2017, federal, state and local governments redistributed $2.8 trillion, or 22% of the nation’s earned household income.

Americans pay $4.4 trillion a year in federal, state and local taxes. Households in the top two earned-income quintiles pay 82% of the tax bill

The amount of (deliberate) misinformation in the "inequality" and "wage stagnation" debates is breathtaking.

ReplyDeleteHealthcare too

Deletehttps://randomcriticalanalysis.com/2017/04/17/on-popular-health-utilization-metrics/

But this misinformation provides jobs for activists, academics, and think tank employees, so it persists

IMHO we should replace TANF, SNAP, SS etc with a UBI and then we will know more.

ReplyDeleteThings like public schools and Medicaid+the subsidies in the PPACA are hard to replace with cash and unfortunately the recipients value them a way below the cost.

I would be concerned that too many people would use the cash for things other than what they are intended for such as food, housing, medical, etc. Then we would have a different problem of giving so much money and yet people are still hungry, homeless, and without medical care.

DeleteMake UBI contingent on sterilization. Fix the prob in 1 gen.

DeleteWon't work if people have already had kids before they apply for UBI.

DeleteI suspect the public argument is actually about wealth, not income. Regardless, a flat post-transfer Gini and an increasing pre-tax one, suggests that taxes are becoming increasingly progressive. Yet, we don’t seem to see that. If anything marginal tax rates (dividend income, Trump cut, etc) seem to have gotten flatter. Perhaps, I am missing the transfer mechanism at work?

ReplyDeleteI suspect your confusion is driven by one or both of the following: (1) the impact state & local taxes and (2) what I'll call the "Warren Buffet" effect.

DeleteState & local taxation has grown persistently larger and more progressive over time. So while federal tax-and-spend policy has arguably been flatish (though see point #2), tax-and-spend taken as a whole has not due to the state & local impact.

The other thing to know is that the Gini coefficient measures the ENTIRE income distribution, while modern U.S. income inequality debate tends to obsess over the tails (particularly how the very rich stack up against everyone else). So while our political debates may not focus on how someone making $300K/year has compared to someone making $50K/year over the decades, from a Gini coefficient perspective it drives a huge part of the result.

Just out of curiosity, does anyone know how the time series of the Gini coefficients look for wealth? This is not a question to imply in any way that we should tax wealth. I am just curious how that time series looks relative to that of income.

ReplyDeleteTop 1 percent’s share of wealth has increased since 1989, see https://equitablegrowth.org/the-distribution-of-wealth-in-the-united-states-and-implications-for-a-net-worth-tax/.

DeleteGini is for income and not wealth. However, it's really hard to accumulate wealth without an income, unless as an individual you luck out and inherit "wealth." Part of the wealth problem is valuating it - income is much easier to measure because it's typically in the form of a paycheck. But, as an individual you can also earn an "income" through returns on investments, through using savings and/or inherited wealth generators. The Gini Coeff. Was at .40 in the 90s and has grown to .48-.49 since then. This isn't a pretty picture.

Delete> Top 1 percent’s share of [mystical social] wealth

DeleteNow this is objective.

Hi John:

ReplyDeleteis there a link to a paper with their methodology? That's a pretty striking difference, I'd like to see how they come up with their measure (black line).

Well, if MPC is 1, then there's no saving - and you need savings to invest and take advantage of compounding interest, buy a home, etc. So let's not throw away income equality just yet in favor of consumption inequality.

ReplyDeleteThe title of my December 2006 WSJ heresy -"The Top 1% of What?"- was picked for a reason.

ReplyDeletePiketty and Saez define income to mean pretax, pretransfer income reported on individual tax returns.

That assumes no government taxes, transfers or redistribution, so doubling tax rates or tripling transfers would have no effect on the accounting (but a huge effect on behavior).

Census data are almost that bad, excluding most transfers and taxes. But measuring income from 1040 tax forms, as Piketty and Saez do, treats shifting business income from a corporate tax form to an individual tax form as if it meant "rich getting richer" rather than more business and professional income being passed through to taxable individual returns rather than stashed in tax-deferred retained corporate earnings.

I was right. They're still wrong.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB116607104815649971

Yep. The tax burden has shifted along with stagnating wages. Not a pretty picture for individuals.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteIf only the public discourse was not drowning in the noise of identity politics... Personally, I'd rather hear about those sorts of things.

ReplyDeleteI was wondering if this finding also tells us something about the other source of inequality that is at the center of the attention, maybe even more than income inequality, being wealth inequality. In that regard, this post made me think about your recent NBER video-seminar on long-term investors in which you highlight the importance of the payoff perspective. For a long-term investor, the true riskless asset is a Perpetuity. The price of this Perpetuity could change, but if you are interested in the long-term, you can disregard short-term variations in prices, and keep on enjoying your riskless dividend stream; to cite one insightful example from your video, as your mom used to say when prices were high ‘those are just paper profits’. Using the same logic, if the government guarantees through income redistribution that income inequality stays almost constant, does wealth inequality really matter?

ReplyDeleteI'm curious as to why the pre-tax & transfer income gini is so low, compared to other data sources (e.g., SCF, where it's closer to 0.6 in recent years). Are any data on income, particularly at the top, missing? Regardless, inequality in consumption is probably more relevant than any income inequality measure, and consumption inequality still may be tracking income inequality -- e.g., Aguiar and Bils (2015, AER).

ReplyDeleteTo be fair the majority of the left does not ignore the impact of taxes and transfers; it's really only Saez & Zucman and their ilk who do so. You can find plenty of "same side" critiques of this misleading approach.

ReplyDeleteEither way though, the U.S. Gini coefficient trend over time has very little to do with our modern income inequality debate. Progressives are focused solely on the tails of the income distribution (those making over $400K/year in Biden's world, for example), whereas the Gini coefficient is a comprehensive measure. And the few remaining old school liberals are concerned that, on a comparative basis, the U.S. Gini coefficient is poor relative to other developed countries (which is true).

I'm not saying our political obsession with the outliers and how we stack up against declining EU powers is CORRECT -- I personally think it makes zero sense* -- just that Gramm & Early aren't really addressing anything of relevance here.

*Of course as part of the disappearing center left, very little of 2021 politics makes sense to me.

Dr Cochrane - Gramm & Early adjust census income data to remove federal and state income taxes paid from incomes - relatively lowering higher-wage earners income more than lower wage earners. They also add in transfer payments - relatively raising lower-income earners incomes more than higher-wage earners.

ReplyDeleteThere are two additional adjustments to census income data Gramm & Early omit. Census income data does not include income from capital gains. Adding that in would significantly raise upper incomes. They also don’t adjust for payroll taxes paid, which is disproportionately borne by the poor.

If they did make these adjustments, what do you think that the trend would look like? I would hypothesize we see a trend toward a more inequality over time (ie, a higher Gini).

You are correct, I think, that using Gramm & Early defines inequality in a way that won’t fix it.

Gramm and Early do indicate that their measure is 'earned income', not 'total income' or 'gross income'. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-truth-about-income-inequality-11572813786?mod=article_inline

DeleteThe numbers would change if the comparison was based on 'total income', but Gramm and Early are arguing that the 'earned income' figures put out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics is what counts. Do their adjustments make sense when 'unearned income' is excluded from the statistics they put forward to frame the debate? Perhaps not.

Gramm and Early's two essays in The Wall Street Journal are attempts to re-frame the context of a political debate in Washington.

DeleteThe economic question is not whether the tax-and-transfer paradigm will be shifted towards the pro-tax-pro-transfer political side or towards the anti-tax-anti-transfer side, but "what will be impact on economic activity and government revenues if the one or the other side prevails?"

Does ever higher rates of progressivity in the income tax code improve general social welfare or diminish it? At what tax rate is the incentive to work flipped to a disincentive? Is that even conceivable in America?

> general social welfare

DeleteThere is no Garden Of Eden, only the individual welfare hated by Leftists and Christians.

Wealth inequality is also very different from what it is said to be. Must be, if it weren't for the definitions being used.

ReplyDeleteSaez and Zucman measure wealth by capitalising income streams. Then insist that we cannot do that with any government aid, benefit, services etc. Now, take the $2.8 billion, capitalise it (20 years is a reasonable rule of thumb) and we've $50 trillion odd. That is, we've moved $50 trillion of wealth by their own logical methods.

Household wealth in total is $130 trillion or so. If we've moved $50 trillion then we've significantly changed the wealth distribution.

Or as we might put it, why do we have a welfare system? Because it makes us all richer in a very real sense. Which, without irony, it does. Some form of welfare system, whether run through govt or not, charity only or not, is going to make the society as a whole richer. Cool - so we'd better measure how rich we are after the things we do to make us richer then.

I had once heard from a cynical soul in college that welfare is the least amount it costs to prevent a riot...

DeleteI've often calmly debated inequality warriors by asking them: why does their arbitrary standard of "enough" become the defacto definition? By all accounts, they ( high earning techies) make orders of magnitude more than what they "need". Isn't it similarly unseemly to be buying teslas and high priced electronics while millions are starving?

ReplyDeleteIncome and wealth are markers of behavior. Do the Gini-equivalent between married and unmarried families.

ReplyDeleteIn an opinion essay Gramm and Early present what purports to be a journalistic scoop: the left wing ignores taxes and transfers! See, we told you, the left wing argues inequality in bad faith!

ReplyDeleteBut, with very little digging this amateur investigator found this:

"Researchers often capture levels of redistribution as the difference between inequality 'before' and 'after' these taxes and transfers are taken into account."

(From "Income Inequality in the United States in Cross-National Perspective: Redistribution Revisited", LIS Center Research Brief, 1/2015.)

Oh, and by the way, WSJ opinion pieces are not usually introduced as source material for scholarly debate.

What is the optimal level of inequality for economic growth? Is there such a thing as an optimal level of inequality? Redistribution affects incentives, which is the engine of economic growth. So zero redistribution and zero barriers for competition should be the optimal. Do we care about who is left behind? If yes, we go back to apply redistributive policies. Perhaps the question should be who don't we want to leave behind? The people with pre-existing conditions? And what kind of pre-existing conditions? Is not being talented, or being less talented, a pre-existing condition? In this whole debate about inequality there are many questions that should be asked and we are just fixated with (pre-tax) income or wealth inequality. The Berkley prof wants to tax the super wealthy, but for what purpose? So that they are less wealthy? It would be fun to run an experiment: if tomorrow we all start our day having the same wealth, how long would it take to see wealth inequality again? I bet not too long because we are not made to be (or want to be) equal. We want to be different, to have more than our neighbor, our brothers and especially more than our brother in law. Without that desire to be different (unequal!) there is no innovation or economic growth. Sorry for the long post.

ReplyDeleteA 2019 on-line video from the Cato Institute features John Early discussing his findings on the topic (see URL, below). A copy of his slide presentation is also available for download at:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.cato.org/events/economic-inequality-are-we-measuring-it-right-what-does-it-mean

Early's Bottom-line: The GINI index for the U.S. is in-line with that of other OECD countries, when the effect of transfers is properly taken into account.

Old Eagle Eye, I quickly compared your source (Early, presentation slides) to mine (LIS Research Brief from 2015, cited above) and the Gini-coefficient data are roughly comparable. Again, there is no big scoop here.

DeleteOne difference that I found interesting: the LIS report shows that the U.S. is on the extreme right tail of the inequality distribution, almost the outlier. (And it is so in both before and after tax-and-transfer conditions.)

Early doesn't mention that, as presumably this fact works against his argument and bias.

How does the fact that a great deal of the transfer payments are paid for with borrowed money (i.e. deficit spending) enter into the equation? If I receive a transfer payment today with borrowed money that I (or a future generation) will have to pay off through higher inflation, higher taxes or lower future transfer payments, should that be considered income in the inequality debate? My guess is that all of the deficit spending will be paid for (one way or the other) by all of us not just the top 10%.

ReplyDelete"Households in the top two earned-income quintiles pay 82% of the tax bill"

ReplyDeleteThis statement ignores the impact of non-earned income and the taxes paid on it. I.e. Pension and retirement distributions are not earned income, and the recipient may (well, probably does not) have any earned income, and they may pay a very significant federal 1040 tax bill (thanks to RMD's required minimum distributions).

So these persons become high taxpayers in the bottom quintile "wage" earners further distorting the analysis of transfer payments.

"If your game is to argue for more taxes and transfers to fix income inequality, that is a dandy subterfuge as no amount of taxing and transferring can ever improve the measured problem!"

ReplyDeleteI am not sure this is quite correct. I think some people, including some economists, who argue for increased taxes on rich argue that the increase in incomes for individuals with the highest incomes are due to economic rents. By increasing taxes, and reducing the benefits for bargaining for larger incomes, the rents earned by the highest income individuals will decrease, which will increase the incomes of lower income individuals. These two factors working together would lower pre-tax income inequality. I personally don't think this is correct, but I think it would explain a process by which higher taxes would reduce pre-tax inequality.

If Gramm and Early are going to count Medicare and Medicaid shouldn't they likewise count employer paid health insurance ?

ReplyDeleteAuten-Splinter et al found that almost all of the apparent rise in income inequality is caused by 2 things:

ReplyDeletethe relative decline in the size, and hence number of earners, of low income households

The rise of pass-through income after the 1986 tax act which had previously been classified as corporate income

http://davidsplinter.com/AutenSplinter-Tax_Data_and_Inequality.pdf