Our great experiment in monetary economics continues.

The news of the moment is that inflation might--might--be peaking. I just present the CPI to make the point, but there seems to be a lot of news suggesting that inflation is easing off. Jason Furman's twitter is a great source of up to the minute detailed data and analysis suggesting this view.

Of course this could also be a blip like August. And new shocks could come along. But let's explore what peaking might mean.

As I've written before (WSJ oped, "expectations and the neutrality of interest rates," short version, "Inflation past present and future" "Fiscal histories" and many more) we are in the midst of a grand experiment in monetary economics. The core question: is inflation stable or unstable under an interest rate target?

Traditional theories and most conventional policy analysis states that inflation is unstable under an interest rate target. If the interest rate is below the current inflation rate, inflation will spiral upwards. Inflation cannot come down until the interest rate is above the current inflation rate and stays there. By this theory, inflation should still be spiraling up.

Newer theory, which primarily uses rational (better, forward-looking or model-consistent) rather than adaptive expectations, says that inflation is stable under an interest rate target. It follows that inflation can go away all on its own, even with interest rates substantially below inflation.

With fiscal theory + rational expectations, we are having a burst of inflation to devalue government debt, as a response to the 2020-2021 fiscal blowout. But once the price level has risen enough to bring the real value of debt back, it's over. Until the next shock hits.

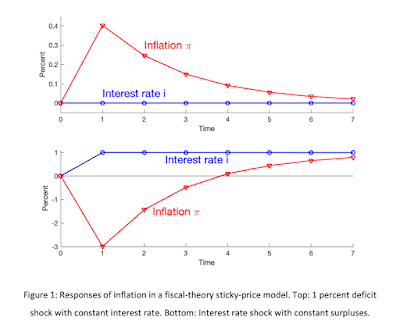

This graph from Fiscal Histories illustrates:

The top graph illustrates what happens in response to a fiscal shock. There is a bout of inflation which devalues debt. But it goes away eventually even if the Fed does nothing, as in that simulation. The bottom graph says that the Fed can help in the short run by raising interest rates, offsetting some of the inflation at the cost of larger future inflation.

Well, if inflation fades away despite interest rates below the inflation rate, we have a rather striking confirmation of this rational expectations view, with stable inflation, relative to the traditional spiral-away view. So, are we headed there? It's too soon for this cautious commenter to declare victory, but I am willing to provide context and say I'm watching anxiously!

I read that a bit in the writings of commenters in the traditional style, such as Furman, Summers and Taylor. Though calling for higher interest rates, none seems to call for interest rates substantially above 8% (current inflation) or the 12% or more that a Taylor rule might recommend. A few more increases to 4 or 5% are enough. They seem to view that the "underlying" inflation is lower, 4 or 5%, and also note that inflation expectations as measured are still in that range -- direct evidence against the adaptive expectations view underlying the traditional spiral. (I don't have links, so apologies if I'm characterizing their views wrongly. This is aggregated over several months.) Well, a return to 4 or 5% is also what the top simulation suggests.

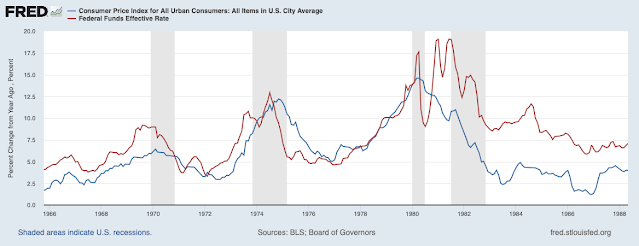

I say "second" experiment because we've been here before. See above, 2008. (Sorry for repeating the point, faithful readers.) Then, we had deflation below the interest rate, the Fed couldn't move, and the traditional view said deflation spiral. That didn't happen either.

The 1970s are the other interesting piece of history.

1980 is the poster chid for the view that interest rates must be substantially higher than inflation before inflation will decline. But look harder at 1975. Inflation did go down, on its own, with interest rates that never exceeded inflation. Inflation didn't get all the way back to 2%, and then rose again. One can argue about just why. But the simplistic view that inflation will never decline until interest rates are substantially above inflation wasn't really true then either.

Usual disclaimer: all of these dynamics presume there isn't another inflationary shock. The chance of a budget blowout seems small right now, but a bad turn in Ukraine, Taiwan, Middle East, or elsewhere could knock over the lab table. There is also a delicate question whether, having crossed the fiscal rubicon, even "smaller" current deficits are inflationary.

Timely and important post. Interest rates are the price of loan funds. The price of money is the reciprocal of the price level.

ReplyDeleteLink: George Garvey:

Deposit Velocity and Its Significance (stlouisfed.org)

“Obviously, velocity of total deposits, including time deposits, is considerably

lower than that computed for demand deposits alone. The precise difference between the two sets of ratios would depend on the relative share of time deposits in the total as well as on the respective turnover rates of the two types of deposits.”

RATE-OF-CHANGE IN DDs in American Yale Professor Irving Fisher's truistic "equation of exchange", where M*Vt = P*T

07/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.195

08/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.28

09/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.143

10/1/2022 ,,,,, 1.141

11/1/2022 ,,,,, 0.906

12/1/2022 ,,,,, 0.594

01/1/2023 ,,,,, 0.603

02/1/2023 ,,,,, 0.543

03/1/2023 ,,,,, 0.459

Long-term money flows, the volume and velocity of money, the proxy for inflation, is falling, while short-term money flows the proxy for real output is rising.

DeleteThis is confirmed by Atanta’s gDpnow @ 4.3% and Cleveland’s CPI inflation nowcast for the 4th qtr. of 2022 @ 5.14%

That's an excellent example of money demand. All monetary savings originate within the payment’s System. And banks do not loan out deposits, they create deposits. Bank-held savings have a zero payment’s velocity. It’s Stock vs. Flow. The expansion of interest-bearing saved deposits makes no contribution to gDp.

ReplyDeleteWhat about the Fed's other mandate of Full Employment? Summers suggested a period of years at n (Years vary based on UNRATE) to really bring down inflation. Currently the UNRATE is well enough below the Fed's historical NAIRU of 5% Will the Fed keep raising rates until UNRATE hits 5% ? So far they seem to be sticking to the past when it comes to NAIRU: keep raising rates until UNRATE hits 5% But the other wrinkle in this is the somewhat stagnant LFPR (CIVRATE).

ReplyDeleteHey! There is an error in the paragraph above the second figure (Second sentence - has rise instead of has risen).

ReplyDeleteAlso, I am fairly new to economics so I am sorry for stating something that should be obvious. I was wondering if applying interest rate above inflation (1970s graph) could have led to a decline in inflation ( later in 1975) due to some persistent effect. Hence, it does show evidence for the adaptive expectations model.

Please let me know what you think. I enjoy your reading your blogs!

Hey! There is an error in the paragraph above the second figure (2nd Sentence - you have used ‘has rise’ instead of ‘has risen’).

ReplyDeleteAlso, I am fairly new to economics so I am sorry for asking something that should be obvious. I was wondering if applying interest rate above inflation rate (1970s) could have led to the decline of inflation (1975) due to some persistent effect. Hence, it does provide evidence for the adaptive expectations theory.

Please let me know what you think.Also, I enjoy your blogs!

P.S. I used my real name after reading your notes.

The vertical gray bars indicate periods in history when the economy was officially in an economic recession, i.e., negative economic growth. The chart at the top of the article is incomplete. It leaves out the rate of unemployment and the key interest rate--the U.S. bank prime rate. In contemporary times (e.g., today), the U.S. bank prime rate is 3 percentage points above the FOMC's Fed Funds Rate. Commercial banks lend at prime plus a margin (measured in basis points) over the prime rate. It is this rate that determines the cost of funds to small and medium-sized firms which typically rely on commercial banks for working capital financing and term loans. A Fed Funds rate of 4% implies a prime rate of 7%; a 6% Fed Funds rate, a prime rate of 9%, etc.

DeleteLikewise for the mortgage rate. Today's The Wall Street Journal has some useful articles in it dealing with Central Bank policy viz., reducing the rate of inflation. One article describes the approach being taken by Tiff Macklem, Gov. of Canada's central bank. Macklem's focus is on the unemployment rate which he describes as being "unsustainably too low". His bank's policy is to raise the bank rate to drive unemployment higher in order to curtail what he describes as "excess demand" in the Canadian economy. In short, he is pressing for a recession, i.e., those vertical gray bars in the top chart, to curtail price changes. The interest rate is simply one means that a central bank can affect price level changes by causing distress via rapid increase in the unemployment rate. It works, and 2020 was the latest example, before the pandemic took hold. 2006-2007 was another contemporary example, but it went wrong, catastrophically, for the FOMC and Wall Street.

The only tool, credit control device, at the disposal of the monetary authority in a free capitalistic system through which the volume of money can be properly controlled is legal reserves. The money stock can never be properly managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit. And Powell eliminated required reserves.

DeleteCentral bankers rarely 'control', but seek to influence the 'cost of credit'. We've seen this quite clearly in the course of the past year. Rates on long-dated Treasuries increased independently of the rate of increase of the Fed Funds Rate, to the point where the yield-to-maturity is between 4% and 4.5% per annum once it became clear that the FOMC would be pursuing a policy of raising the administrative rate of interest to contain the rate of inflation. Now, long-dated Treasuries are a long ways away from the heights reached under Paul Volcker's chairmanship of the FRB, and it is not to be expected that the FOMC under Jerome Powell will lift short-dated Treasury yields as high as Paul Volcker's FOMC (20% to 22%, if memory serves) did in the early 1980s. Nevertheless, the actual interest rates today are far higher than we've seen since 2010, and that is having its effect, albeit not yet disasterously so, on the economy (cf. mortgage rates). Jerome Powell is not through yet, and we may see some surprises in the months to come that could be unpleasantly unexpected.

DeleteMonetarism has never been tried. Volcker never tightened monetary policy, except for Feb, Mar, Apr, of 1980 or the Emergency Credit Control Program (he let the economy burn itself out).

DeleteIn regulating the money supply the monetary authorities using monetarist guidelines (its power to control of the volume of Reserve bank, & commercial bank credit) should be cognizant of the volume & rate of change of monetary flows, i.e., the volume of money times its (transactions) rate of turnover. It is obvious that the extent of money’s impact on prices & the economy is measured by monetary flows, not the stock of money. If the transactions velocity of money were a constant it would not matter, but money turnover has fluctuated widely.

With the intro of the DIDMCA, total legal reserves increased at a 17% annual rate of change, & M1 exploded at a 20% annual rate (until 1980 year’s-end).

Why did Volcker fail? This was due to Volcker's operating procedure. Volcker targeted non-borrowed reserves (@$18.174b 4/1/1980) when at times over 100 percent of total reserves (@$44.88b) were borrowed (i.e., absolutely no change from what Paul Meek, FRB-NY assistant V.P. of OMOs and Treasury issues, described in his 3rd edition of “Open Market Operations” published in 1974).

Richard G. Anderson reconstructed legal reserves to show that required reserves didn't increase. This was wrong. 35% of the nonbanks required reserves were added, adjusted, to show that there was no increase.

DeleteThe money multiplier, required reserves, the truistic monetary base, was drastically altered.

We knew this already: In 1931 a commission was established on Member Bank Reserve Requirements. The commission completed their recommendations after a 7-year inquiry on Feb. 5, 1938. The study was entitled “Member Bank Reserve Requirements — Analysis of Committee Proposal” its 2nd proposal:

“Requirements against debits to deposits”

http://bit.ly/1A9bYH1

After a 45-year hiatus, this research paper was “declassified” on March 23, 1983. By the time this paper was “declassified”, Nobel Laureate Dr. Milton Friedman had declared RRs to be a “tax” [sic].

Very timely that in the current environment, fiscal not monetary theory explains a lot of inflation. But could it be that monetary-explained inflation is an independent (of fiscal) component of inflation or does fiscal theory incorporate it? Example:Expected, not actual, economic activity driving inflation or deflation.

ReplyDeleteExcept. We probably have current job destruction with interest rates below inflation because of the glut of zombie companies. They could barely survive, but the one+two of inflation and interest rates finally puts the stake through their heart.

ReplyDeleteThe untold story of 1982 was probably the zombie companies of the 70's were finally killed and the resulting growth was more "alive".

If this is just a flash crash of 5 months, lots of those zombies will still be on life support... and will continue on life support, so long as they can service their debts cheaply...

Just a thought.

I have a question what if the interest rate decreases then what will happen to inflation?

ReplyDeletehttps://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=5996547460390135&set=a.165771190134487

ReplyDeleteA lot of comments and theories on inflation over the past several months. If you look at the monthly figures on the CPI (since July) and PPI (since July, and they are all negative), and the PCE (since July) that the Fed follows which has returned to normalcy -- where do you think we will be by next June?

Unemployment is around 3.5%.

Have you been following GDP releases (and the Atlanta Fed model)? 3rd Qtr (first est.) reported at 2.6% -- so we are no longer in a recession. The Atlanta Fed model shows the 4th Qtr (as of now) at 4%. We will get a 2nd estimate of the 3rd Qtr report later this month -- likely to be upgraded closer to 3%.

The only bad numbers, from my point of view, is the labor productivity rate.

What caused this inflation, John? As I said a few months ago:

1. The Pandemic was a shock to the international distribution system. Look at February thru April of 2020. Exports in China, Japan, Germany, the U.S., and our neighbors in Canada and Mexico all took a big hit.

And the Unemployment Rate in April 2020 jumped over 10 percentage points in that one month -- there has never been anything near that in our history -- even over several months; not even during the Great Depression.

Look at the monthly jobs reports we have been getting -- now about 200k per month, which is more normal for a good year. The Labor Force is back where it was; and the labor force participation rate and the employment-population ratio, while not good, is back near where it was and never was that good to my liking.

2. And in the U.S. the fiscal stimulus was overwhelming. Check the PCE rates. They have tapered off now in the last several months. A demand that couldn't be matched with a broken international supply chain.

The Ukraine War and oil/energy are factors; but they are not driving the inflation numbers in the U.S. economy. Look at the numbers since July, all good while the war has gone on and oil between $120 and $90. Europe may have a problem; we do not.

The Fed is doing a great job as far as I'm concerned. They have been a little behind, but they are engineering a soft landing. If we went by the Taylor Rule we would have had a Fed Funds rate around 6% or more in 2021 and killed any recovery that we now have, and where would Unemployment be and what would the monthly jobs report look like.

So where do you think we will be next June? How 'bout Inflation no more than 4%, probably somewhere between 3% and 2%; a Fed Funds rate a little above that, just over 4%; I'm not sure of Real GDP but at least 2%; Unemployment around 4% or less; jobs added at a normalized 200k per month.

I've got your Fiscal Theories all marked up:

For the Macro-Economy:

1. What causes inflation? Frictions -- that develop in dynamic economic behavior that throws off the normal operating system causing inefficent adjustments.

2. What drives inflation? Imbalances -- that result from the frictions as the different players readjust. We have inequalities that result from the persistent imbalances.

Define inflation (at the macro level) -- a rise in the price level without a concomitant increase in productivity. (I'm paying more, but am I getting more? or, I'm doing the same work, and getting paid more.)

See the chart I have posted -- you can offset the effects of inflation if you have good productivity. The monetary policy usually, not always, follows what goes on in the economy; rarely does it lead the economy.

And I don't know what to tell you about the expectations of investors; but, we have no problems financing our debt, and we do roll it over, and we can shorten or lengthen the term (to take advantage or avoid) the market interest rate environment. You do know we have somwhat of an inverted yield curve, right now, right?

John, substitute this link for the one in my original comment -- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=6000879226623625&set=a.165771190134487

DeleteJust like in 1951, the FED is forced to acquiesce to the Treasury with such large deficits.

Deleteit was very grate information.

ReplyDeleteAll the analysis makes me wonder one thing: Is the power of the Fed being overestimated with regard to its addressing inflation? Are there underlying persistent structural forces that over time blunt any Fed action?

ReplyDeleteI think the on-going Quantitative Tightening is significant here, and not discussed in this post.

ReplyDelete“I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it.” - William Thomson, Scottish physicist (1824-1907)

ReplyDelete• Lecture on "Electrical Units of Measurement" (3 May 1883), published in Popular Lectures Vol. I, p. 73

---------------------|

Velocity: Money's Second Dimension - By. Bryon Higgins

"Money has a 'second dimension’’, namely, velocity . . .. " Arthur F. Burns in Congressional Testimony.

“The rapid growth in M1 velocity for the past three years is particularly surprising when one considers the accompanying pattern of increases in market interest rates. One of the primary factors contributing to the normal increase in velocity during periods of economic expansion is the rise in market interest rates that typically accompanies rapid economic growth. Businesses and households intensify their efforts to economize on cash balances as the opportunity cost of holding money rises. A substantial portion of the increase in velocity during the current expansion occurred in 1975 and 1976, however, a period in which market rates were generally declining. Thus, the interest sensitivity of the demand for money does not provide a complete explanation of the behavior of velocity in the current recovery.”

www.kansascityfed.org/PUBLICAT/ECONREV/EconRevArchive/1978/2q78higg.pdf

FED WIRE transactions are up.

Deletehttps://www.frbservices.org/resources/financial-services/securities/volume-value-stats/quarterly-stats.html

I think we all need to take a break from theory.

ReplyDeleteLook to history.

Any country that excessively prints more money than it collects... Eventually gets into trouble.

Every time. (Rogoff Reinhardt sound familiar?)

Sometimes that decline takes decades, but it happens.

So we can balance our budget, or we will have inflation; and that inflation will eventually equal the overspending.

Of course I'm open to any 100 year study that says otherwise.

We need to take a much longer view than just a decade, perhaps a 50-80 year timeframe. We should also acknowledge the "buffer" of the Dollar's seigniorage when talking about inflation in the USA versus inflation in Venezuela.

ReplyDelete2400 years of History tells us when you consistently run a deficit, you will have inflation. (Reinhardt and Rogoff, Diacletian, etc.)

If we look at our overspending for the last 50-80 years, our inflation will likely correspond to our deficit spending. And our deficit spending is only going to increase over the "foreseeable future."

So, next year, inflation may temporarily come down to 2% with a recession, but it will likely increase to 4%+ after that... on its way to 10%... or even higher.

Of course, we don't need new experiments to see how this turns out - look to any 50-100 year time-frame in history and explain to me how it's "different this time"...

History -- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=6003515429693338&set=a.165771190134487

ReplyDeleteThe only time we didn't have a national debt was from the 1830s up to the Civil War. If you want to look at our debt hangover, you need to relate it to our productivity. We do not payoff our debt; we roll it over. Our ability to finance our debt depends on how competitive we are with other countries -- the international investment outlook.

During the Great Depression, both Roosevelt and Hoover in 1932 ran on platforms calling for balanced budgets.

DeleteBetween 1929 (@ $183.2b) & 1939 (@ $189.9b), there was no overall expansion of net debt (within the Great Depression). Then during 1940-1945 total real debt expanded by approximately $193.5b (therein cumulative net debt doubled in 5 years).

The election is over. We'll see what happens now.

ReplyDeleteInflation comes down when nominal GDP comes down. From 1971 to 1979 nominal GDP growth was too high and was generally accelerating despite generally rising interest rates. That was the cause of inflation that peaked in 1980. Nominal GDP growth today is still wildly high but it has declined from the peak. Is this decrease in GDP growth rate, with interest rates still below the inflation rate proof that inflation is stable? I think it just proves that the Nominal GDP trend is a much better indicator of how you are doing controlling inflation than are interest rates relative to the inflation rate. If the Fed succeeds in getting inflation under control without raising rates above the inflation rate the only thing we know for sure is that the Fed is more serious about controlling inflation than it was in 1971 or 1979.

ReplyDeletehttps://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Wrow

Peaked? The Biden Trillion hasn't even hit the streets yet.

ReplyDeleteIMHO, I think it has. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=WtTP

DeleteFrom The Wall Street Journal online, today:

ReplyDelete“I’m looking at a labor market that is so tight, I don’t know how you continue to bring this level of inflation down without having some real slowing, and maybe we even have contraction in the economy to get there.”

— Kansas City Fed President Esther George.

Shades of Paul Volcker?

Perhaps, the FTPL might be of some assistance at this point.

Economists simply can’t differentiate between an individual bank and the system. The equation, the capacity of a single bank to create credit as a consequence of a given primary deposit (and newly created deposits flow to other banks), is also applicable to a nonbank, financial intermediaries.

DeleteBut this comparison is superficial since any expansion of credit by a commercial bank enlarges the money supply, enlarging the system, whereas any extension of credit by an intermediary simply transfers ownership of existing money within the system (a velocity relationship).

It is not clear from your remarks, immediately above, in what way your observations relate to Kansas City Fed President Esther George's concerns related to contraction of the economy as an avenue or policy objective to reduce the rate of inflation (in the price level) in the U.S.

DeleteEnlargement of the money supply (in nominal terms) does not enlarge the "system" (i.e., the real economy). An expansion of Y (nominal Income) does not in and of itself give rise to an expansion of y (real or deflated Income). In order to expand y, one needs to produce more real goods (wealth), whereas an expansion of Y can occur as a result of an expansion of the money supply without a concommitant increase in the output of real goods. Some economist hold with the view that inflation is the persistent increase in the broad price level that arises when expansion of the money supply increases at a rate faster than the growth rate of real economy (real goods). Cf., Bushe, K., and S. Easton, "On World-Wide Inflation", FOCUS, no. 12, 1983. Vancouver: The Fraser Institute.

In the present case, the surge in the rate of inflation is an outcome of the monetization of the 2020-21 fiscal deficits in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and elsewhere. Central banks, and their presidents and governors, let down their guard. See, for example, remarks by J. Powell in 2021 regarding the FOMC's revised policy of allowing inflation to run a little higher than the 2% target in order to even out the cumulative rate of inflation following a spat of lower than 2% annual inflation upto that point in time. Things didn't work out the way J. Powell imagined they would, and here we are with the FOMC and Fed Presidents now running hot to restrain the inflation rate and bring it down to the 2% target level, and talking Volcker-type recessions as a necessary condition of re-attaining the 2% target in as short a period of time as humanly possible. It was painful in Volcker's day; it will be doubly painful in present tense.

That's why you target the level of N-gDp. Short-term money flows translate into long-term money flows, and vice versa. It's just math.

Delete2022 is a good example. As long-term money flows have receded, short-term money flows have rebounded. Atlanta’s gDpnow forecast is @ 4.2% and Cleveland’s CPI inflation forecast for the 4th qtr. is @ 5.23%.

Not that those numbers represent precise estimates, but they demonstrate the trend, the flows.

"It’s something that harks back to Mr. Okun’s point: Curing inflation with recessions can just swap one form of misery for another." Josh Zumbrun, writing in The Wall Street Journal, 11/18/22, "Inflation and Unemployment Both Make You Miserable, but Maybe Not Equally--Tweaking the famous ‘Misery Index’ may help it better fit political events".

ReplyDeleteTo reduce N-gDp, you must reduce AD, or money times velocity.

ReplyDelete“There’s a dirty secret at the heart of economics: Economists–and by extension central banks–understand less about inflation dynamics than we would like to admit.” -- Neil Shearing, Group Chief Economist, Capital Economics, London, England. Full article at

ReplyDeletehttps://www.capitaleconomics.com/blog/we-need-understand-inflation-control-it-thats-problem?mod=djemRTE_h

Like Sumner: 19. November 2022

Delete“I don’t view the monetary aggregate data as having much predictive value.”

Who is Sumner?

DeleteScott Sumner N-gDp level targeting

Delete"NGDP growth equals inflation plus real GDP growth. When there is an adverse supply shock, a 4 per cent NGDP target will result in a brief period of higher than normal inflation. But that’s actually an efficient way of making sure that real wages stay at levels consistent with full employment. In that case, it’s better to keep the workforce employed at slightly lower real wages, than to obsessively target inflation at the cost of sharply higher unemployment. Similarly, during a productivity boom, an NGDP target will lead to a period of below normal inflation. Once again, that’s a feature, not a bug. It keeps labour markets from becoming overheated during a period of rapid growth.

Delete"Economists are beginning to understand that NGDP is the variable we should actually be concerned about. Instead of worrying about what might happen to inflation under NGDP targeting, we should consider what happens to NGDP if we insist on targeting inflation."

S. Sumner (2018-03-28) "The problem with central bankers’ inflation preoccupation", Center for Policy Studies. https://capx.co/the-problem-with-central-bankers-preoccupation-with-inflation/

A natural experiment would have been possible during 2022, had the FOMC taken S. Sumner's policy advice to heart.

That's not the optimum solution. Monetary policy objectives should not be in terms of any particular rate or range of growth of any monetary aggregate. Rather, policy should be formulated in terms of desired RoC’s in monetary flows relative to RoC’s in R-gDp;

DeleteRoC’s in money flows can be used to approximate N-gDp, which can then be used as a subset and proxy figure for RoC’s in all physical transactions P*T in early American Yale Professor Irving Fisher’s truistic “equation of exchange”. RoC’s in R-gDp have to be used, of course, as a policy standard;

Because of monopoly elements, and other structural defects, which raise costs, and prices, unnecessarily, and inhibit downward price flexibility in our markets, it is advisable to follow a monetary policy which will permit the RoC in money flows to exceed the RoC in R-gDp by c. 2 percentage points;

Monetary policy is not a cure-all, there are structural elements in our economy that preclude a zero rate of inflation. In other words, some inflation is inevitable given our present market structure and the commitment of the federal government to hold unemployment rates at tolerable levels;

It's exactly as Lawrence K. Roos, Past President, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and past member of the FOMC (the policy arm of the Fed) as cited in the WSJ April 10, 1986:

ReplyDelete"...I do not believe that the control of money growth ever became the primary priority of the Fed. I think that there was always and still is, a preoccupation with stabilization of interest rates".

The C. D. Howe Institute has this week published a report by S. Ambler (formerly professor at l'École des sciences de la gestion de l'Université du Québec à Montréal, 1985-2020), T. Koeppl (professor, Dept. of Economics, Queen's University), J. Kronick (director, Monetary and Financial Services Research, C. D. Howe Institute), titled "The Consequences of the Bank of Canada's Ballooned Balance Sheet", 11/22/2022. The report is found by navigating to:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/consequences-bank-canadas-ballooned-balance-sheet

"Over the next few months, [The Bank of Canada's] balance sheet ballooned quickly from a size of just over $120 billion [all amounts expressed in Cdn. dollars] in early March 2020 to a peak of $575 billion in March 2021. This increase was largely a consequence of the Bank's quantitative easing (QE) program, which bought up Government of Canada debt across the yield curve, to provide further stimulus to the economy.

"On the liabilities side of the balance sheet, those assets were mostly paid for by increasing the settlement balances held by financial institutions at the Bank of Canada. Such settlement balances increased by three orders of magnitude, from $250 million to approximately $260 billion, implying a massive excess supply of short-term liquidity for Canada's financial system."

In short, the Bank of Canada monetized the Government of Canada's new issue debentures, setting the stage for the burst of inflation that the Bank of Canada is now endeavouring to gain control over via a programme of rapid increase in the Bank's interest rate paid on excess reserves ("settlement balances", in Canadian banking parlance).

One consequence of this has been that the Bank of Canada is paying more in interest to commercial banks than it is receiving on its continued holdings of Government of Canada debentures. The difference is of such consequence that the report authors expect the Bank of Canada to report negative equity in its balance sheet, i.e., the Bank's liabilities will exceed the Bank's assets. The implication, if this occurs, is that the Government of Canada will be required to 'bail out' the Bank of Canada with an equity infusion funded by issuance of Government of Canada debentures that will not be supported by Bank of Canada purchases in the secondary bond markets in Canada.

The report's observations and conclusions implicitly validate the Quantity Theory (re: inflation), and support the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (re: the valuation of federal government debentures). We've not yet seen the full effect of the FTPL on federal government prices, in part because of optimistic over-confidence in the Bank’s management, and in part because the implication of the FTPL on prices of financial assets is the ruin of many investment dealers and a seldom seen Canadian financial crisis of profound proportions.

M2 hasn't changed for c. 1 year. But DDs have risen. I.e., the composition of M2 has changed. So, the "demand for money" has fallen, and thus velocity has risen. So, short-term money flows are rising at the same time long-term money flows are falling. Until short-term money flows reverse, a recession will not happen.

ReplyDelete09/1/2021 ,,,,, 20957.9

10/1/2021 ,,,,, 21098.0

11/1/2021 ,,,,, 21334.5

12/1/2021 ,,,,, 21660.4

01/1/2022 ,,,,, 21636.9

02/1/2022 ,,,,, 21590.5

03/1/2022 ,,,,, 21855.8

04/1/2022 ,,,,, 21860.3

05/1/2022 ,,,,, 21555.1

06/1/2022 ,,,,, 21585.8

07/1/2022 ,,,,, 21578.9

08/1/2022 ,,,,, 21546.5

09/1/2022 ,,,,, 21459.4

10/1/2022 ,,,,, 21362.5

The identity, M v = P y, (income basis) provides that answer. Assume that the total derivative of that identity is C¹, then dM/M + dv/v = dP/P + dy/y. If dM/M = 0, then dv/v = dP/P + dy/y. If the instantaneous change (not the year-over-year change) in the price level is 4/100 annulized and the instantaneous change in real income is 0/100, then the instantaneous change in the velocity of money is 4/100 annualized. If v previously was equal to 1, i.e., v_0 = 1 then v_1 = exp(4/100) = 1.0408... . Is this consistent with your observations?

DeleteM v = P y is a fudge factor. Vi is contrived. It's Vt that's important. For example, in 1978 all economists' forecasts for inflation were wrong. Why? Because Vi fell when Vt rose. The G.6 Debit and Deposit turnover release was discontinued by mistake in Sept. 1996.

Delete"Vi", as you label it, is simply P y / M. Both expressions, M Vi = P y and M Vt = P T, are identities, i.e., tautologies. Given values for any three variables, the value of the fourth follows. 'Velocity', whether income-based, i.e., Vi, or transaction based, i.e., Vt, cannot be observed directly. It is 'implied', by the Quantity Theory. With Vt, you have to count the number of times a given dollar is used in transactions over a given period of time--an impossible task in a contemporary economy. With Vi, one measures M2, say, the price level (index), CPI all urban consumers, say, and real GDP, y, then using all three measured variables, Vi is calculated. On this basis, I can understand your criticism that "Vi is contrived". But, it simply falls out in the wash (i.e., is calculated from the values of the other three variables). In other words, Vi doesn't add anything new to what we already knew before calculating it. The principal theorist of the Quantity Theory was Irving Fisher. A competing version was developed by the Cambridge (U.K.) school that included John Maynard Keynes. Irving Fisher also postulated that the real rate of interest, r, is found from the nominal rate of interest, i, and prevailing rate of inflation, π, e.g., r = (1 + i ) / ( 1 + π ) – 1 . This relation is important to the interpretation of the new Keynesian Inter-temporal Substitution equation in NK-DSGE models because it replaces an unobservable, r, with presumably observable i, and π. Fisher demonstrated his postulate empirically in a series of papers. But this too is a tautology (an identity) insofar as it depends on which nominal interest rate one selects and which measure of inflation one chooses to use in obtaining the value of r. This seems to be the case for much of economic theory. On the one hand..., &c. Kurt Wicksell might have been amazed had he been able to see what gyrations economists go through to explain quite ordinary behaviour. E.g., has anyone observed "aggregate demand", and "aggregate supply" directly? Who has defined "excess demand"? -- a term frequently used by the Governor of the Bank of Canada this year to justify aggressive increases in the Bank of Canada's target overnight rate of interest on 'settlement balances'. On this blog-site, much criticism was heaped on the term "shortages" as being an improper adjective to describe the difficulty in finding and hiring qualified employees earlier this year (i.e. "labor shortages"), given "supply" and "demand" measures might throw greater light on the troubles facing employers and would be employees. Life is a puzzle; then, there is Economics.

DeleteVt was a statistical stepchild. Vt is a real observable statistic. In 1931 a commission was established on Member Bank Reserve Requirements. The commission completed their recommendations after a 7 year inquiry on Feb. 5, 1938. The study was entitled “Member Bank Reserve Requirements — Analysis of Committee Proposal”

Deleteits 2nd proposal: “Requirements against debits to deposits”

http://bit.ly/1A9bYH1

After a 45 year hiatus, this research paper was “declassified” on March 23, 1983. By the time this paper was “declassified”, Nobel Laureate Dr. Milton Friedman had declared RRs to be a “tax” [sic].

Link: The G.6 Debit and Demand Deposit Turnover Release

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/releases/g6comm/g6_19961023.pdf

Because banks don't lend deposits, you can impute Vt. Just take the ratio of transactions' to savings' deposits. Vt plateaued in August.

DeleteMoney flows, which underweights Vt peaked in Feb. Historically, when you get a surge in the money stock, it is immediately followed by a rise in Vt.

Fisher said economics was "an exact science". But Friedman talked about "high powered money" in the same vein as a "tax".

DeleteMilton Friedman, for instance, explains that “Fisher, in his original version, used T to refer to all transactions – purchases of final goods and services…, intermediate transactions…, and capital transactions (the purchase of a house or a share of stock).

DeleteIn current usage, the item has come to be interpreted as referring to purchases of final goods and services only, and the notation has been changed accordingly, T being replaced by y, as corresponding to real income” (Friedman, 1990, p. 38).

Fabulous work Dr. Cochrane! I was just reading your article in the Journal of economic perspective and want to ask about a potential contradiction that I saw.

ReplyDeleteFor the reasoning why the 2008 didn't lead to deflation you state that in reality there should have been a 1930s deflation, but because of government deficits, which caused inflation there would have been. Thus we see higher deficits means lower expected PV of government bonds and thus inflation - so no deflationary spiral because it was repudiated with government inflation.

However, later you use the zero-bounds as a test-case to repudiate monetary and Keynesian theory which would have predicted high, unstable inflation. But, can't they answer that there was high, unstable inflation but it was being added to an otherwise very deflationary environment, so in a similar way we did see the large predicted inflation, but it was being added to a deflationary environment?

What did I not understand?

Good question. It's not so much the deficits we saw that stopped the deflation spiral in 2008, it is the clear expectation that a big deflation would not have triggered austerity to pay a windfall to bondholders. Then we get to the zero bound period, which is a separate question. Yes, the story that our fearless leaders just offset the deflationary spiral with enough QE and monetary hyperinflation that we slept is possible. But seems awfully full of epicycles. "Michelson Morley Occam and Fisher" goes on about this possibility.

DeleteJohn Maynard Keynes wrongly said: that it is an “optical illusion” to suppose “…that a depositor and his bank can somehow contrive between them to perform an operation by which savings can disappear into the banking system so that they are lost to investment…”

ReplyDeleteWhat has happened is there has been a shifting of deposit accounts, that a larger proportion, of a larger volume of bank deposits, is now interest-bearing.

See: “Should Commercial Banks Accept Savings Deposits?” Conference on Savings and Residential Financing 1961 Proceedings, United States Savings and loan league, Chicago, 1961, 42, 43.

But banks don't lend deposits. See Dr. Philip George's "The Riddle of Money Finally Solved"

http://www.philipji.com/riddle-of-money/

Savings transferred through the nonbanks never leaves the payment's system. There is just an exchange in the deposit liabilities between counterparties in the commercial banking system. Savings flowing through the nonbanks increases the supply of savings, but not the supply of money, a velocity relationship.

Japan’s “lost decade” is due to the impoundment and ensconcing of monetary savings in their banks. The BOJ has unlimited transaction deposit insurance, the Japanese save more, and keep more of their savings impounded in their banks.

“Japanese households have 52% of their money in currency & deposits, vs 35% for people in the Eurozone and 14% for the US.”

It's stock vs. flow. Secular stagnation is directly due to the deceleration in velocity.

Keynes was speaking to the situtation in the 1920s and1930s in England. "The payment system", as we know it today, did not exist then. "Vault reserves" were common. Metallic money would readily disappear from the country if the interest rate was too low, relative to bank interest rates outside the country. Fast-forward to today, and we don't see money in ordinary transactions--insert a debit card in an electronic reader, and "whisk", the money (electronic) is transfered from your account to the merchant's account in another bank, or the same bank. And yet, banks still hold "vault reserves" in the form of paper and metallic currency. During the 1970s/1960s, in NY City, the money-center banks would physically convene to cross debits and credits and settle their net debits and credits overnight. Now it is done electronically. This is a far cry from Keynes's day.

DeleteI guess you've never read his book.

DeleteRead his General Theory decades ago, brown trout (sp. salmo trutta).

DeleteFriedman's influence was pervasive. Friedman at "the Chicago School" in 1932:

DeleteFriedman “stopped Viner in his calculus and finally went to the blackboard and worked the whole problem out, which Viner was unable to do”…

In Mints’ class “Price and Distribution” Friedman “discovered some of the errors in Keynes’ fundamental equations. Mints wrote Keynes in Friedman’s behalf – & for the class.

That Keynes admitted the errors and this gave him, at least in part, the impetus to write the General Theory.”…”Keynes’ subsequent repudiation in the General Theory of those parts of the Treatise on Money grew out of these criticisms.”

I don't think Cochrane has to wait for another experiment. The correct response to stagflation is the 1966 Interest Rate Adjustment Act.

ReplyDelete“while the aggregate of time and demand deposits continued to increase after July, the proportion of time to demand deposits diminished. Whereas time deposits were 105 percent of demand deposits in July, by the end of the year, the proportion had fallen to 98 percent. These were all desirable developments.”

M1 peaked @137.2 on 1/1/1966 and didn’t exceed that # until 9/1/1967. Deposit rates of banks decreased from a high range of 5 1/2 to a low range of 4 % (albeit not enough). A .75% interest rate differential was given to the nonbanks.

And during this period, the unemployment rate and inflation rates fell. And real interest rates rose.

The month-to-month change in the producer price index, all commodities, has fallen back into the historical range. See:

ReplyDeletehttps://data.bls.gov/timeseries/WPSFD4&output_view=pct_1mth

-- Note the 2020-2022:H1 period which shows the impact of supply constraints during and immediately following the pandemic restrictions.

The cost-push effect on CPI should, accordingly, abate.

The FOMC is aware of this dynamic. The noise the FRB presidents are making is for the purpose of talking down expectations, for whatever that may be worth.

The 2-year Treasury note yield-to-maturity now exceeds the 10-year Treasury note yield-to-maturity. Historically, this development has presaged the onset of an economic recession in the U.S. The effect of recessions on the rate of inflation has been mixed, historically. The effect of recessions on labor wages and employment has always been negative, with permanent side-effects. The question at issue is whether policy makers learn from their past mistakes, or simply repeat the same lessons over and over again.

“The Fed raising interest rates is by far the most common cause of recessions if you look since World War II. And if they’re raising rates this rapidly … the chance that you overshoot is pretty high.” -- Austan Goolsbee, incoming president and CEO of The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Goolsbee teaches economics at the Booth School of Business, Univ. of Chicago. Quoted in The Wall Street Journal, in a Dec. 1, 2022, article by N. Timiraos.

ReplyDeleteThe impression one derives from reading "Fiscal Histories" is that the FTPL is non-falsifiable. For example,

ReplyDelete"Fiscal theory is consistent with the long quiet zero bound and the silence of quantitative easing. The interest rate target determines expected inflation. Unexpected inflation is determined by news to the present value of future surpluses. Inflation is both stable (no spirals) and determinate (no multiple equilibria or sunspots) at the zero bound. If there is no fiscal or discount-rate news, there is no unexpected inflation either. That’s not proof: I don’t have an independent measure of deficit and discount rate expectations. But fiscal theory is at least consistent with the episode, in a way that conventional theories are not. And it’s at least plausible that the steady recovery after 2009, combined with very low real interest rates, led people not to worry any more or less than before about debt repayment." (Page 137)

Lacking "an independent measure of deficit and discount rate expectations" places the FTPL into the realm of metaphysics. See, for example, the definition displayed in footnote 1 on page 126 of "Fiscal Histories".

In other words, FPTL is incomplete insofar as it depends on unobservable expectations. It is plausible, in logic, but not falsifiable, and therefore not provable.

A second impression one derives from the narrative in "Fiscal Histories" is in the form of question, "Why would anyone hold U.S. Treasuries or U.S. Agency debentures, or Federal Reserve Bank notes, rather than real assets?" Certainly, one must have a certain quantity of bank notes on hand for transaction purposes and to meet tax obligations from time to time, but there is no reason to hold bank notes or Treasuries otherwise. This goes to the heart of an earlier remark concerning unwarranted "windfalls" to holders of Treasuries during periods when the rate of interest paid on issued and outstanding Treasury issues exceeded the concurrent rate of inflation. Apart from some pension funds, life insurers, and money market funds, there is no reasonable purpose to holding government debt obligations.

If there is no reasonable purpose to holding government debt, then it follows that there is an upper limit on the quantity of debt government can reasonably issue. Only the existence of a central bank willing to buy and make a market in government debt without limitation ensures a ready buyer for that debt.

Bottom-line? The FPTL needs further work.

I agree heartily FTPL needs more work. On the falsifiable front, well, that's the point of sticking my neck out here on great experiments. And the zero bound experiment was pretty persuasive too. But most of all, at least grant the FTPL is no worse than the rest of macroeconomics and finance. Are monetarism and Keynesianism more falsifiable? Is behavioral vs. rational finance more falsifiable? One does what one can.

DeleteI concur, and I am supportive of the effort that you've made to popularize the theory because it rings true. "Fiscal Histories" includes a number of very important points regarding the role of government debt and deficit spending in the creation of inflationary pressures.

DeletePerhaps the next phase of work is to look back and discover, if possible, via analyses of relevant economic history where the FTPL would have predicted a burst of inflation based on information available at the relevant moment in time. The economic history of the Republic of Argentina may be a very rich lode to mine for this purpose; divided, for example, into the period of British dependency, the period following the throwing off of British dependency, the period pre-Peron, the Peron period, and the post-Peron period. The interaction between the fiscal and monetary authorities in each period and the resulting price level changes, currency debasement, currency controls, inflationary cycles, etc., is well-documented. The U.S. itself, is also a rich vein of material for the FTPL. The effort could be supported and undertaken in conjunction with one or more Hoover research fellowship (if such a program exists).

A thought experiment, Gedankenexperiment, such as Einstein's Theory of Relativity and Theory of General Relativity, does not have to be proven to have force. Proof can follow later, as it did with Einstein's theories.