An email correspondent sent the above graph. The title is [Federal Reserve] Liabilities and Capital: Liabilities: Earnings Remittances Due to the U.S. Treasury.

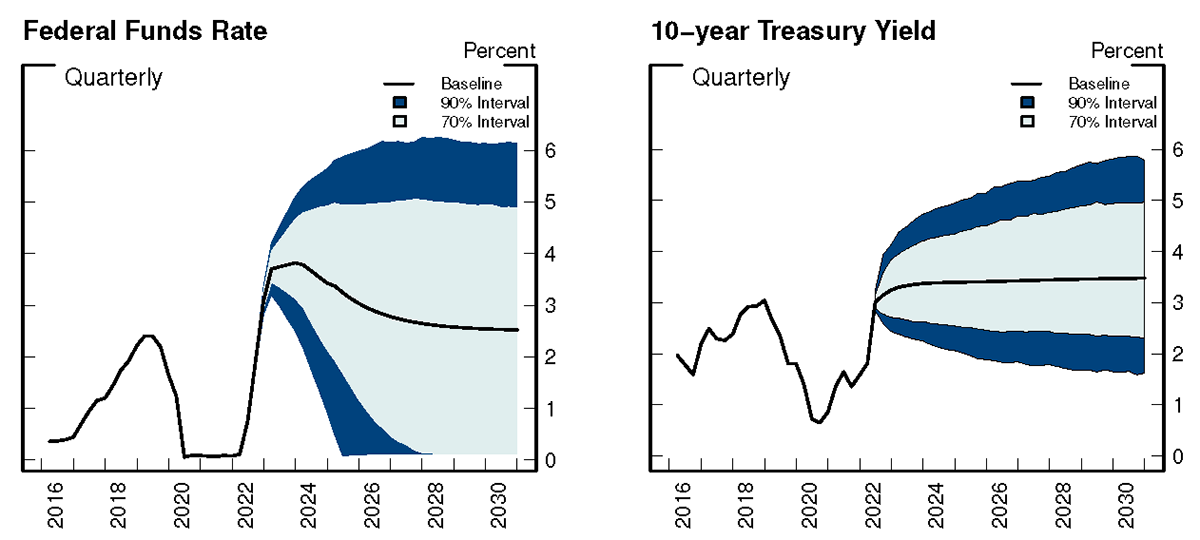

The Treasury pays the Fed interest on the Fed's asset holdings. The Fed pays interest on reserves to banks and to other financial institutions that have, effectively, deposits at the Fed. As long as Treasury interest is greater than interest the Fed pays, the Fed makes money. It spends some, and returns the interest to the Treasury. The Fed also issues cash, which pays no interest, so the Fed makes steady money on the difference between interest bearing assets and the zero return of cash.

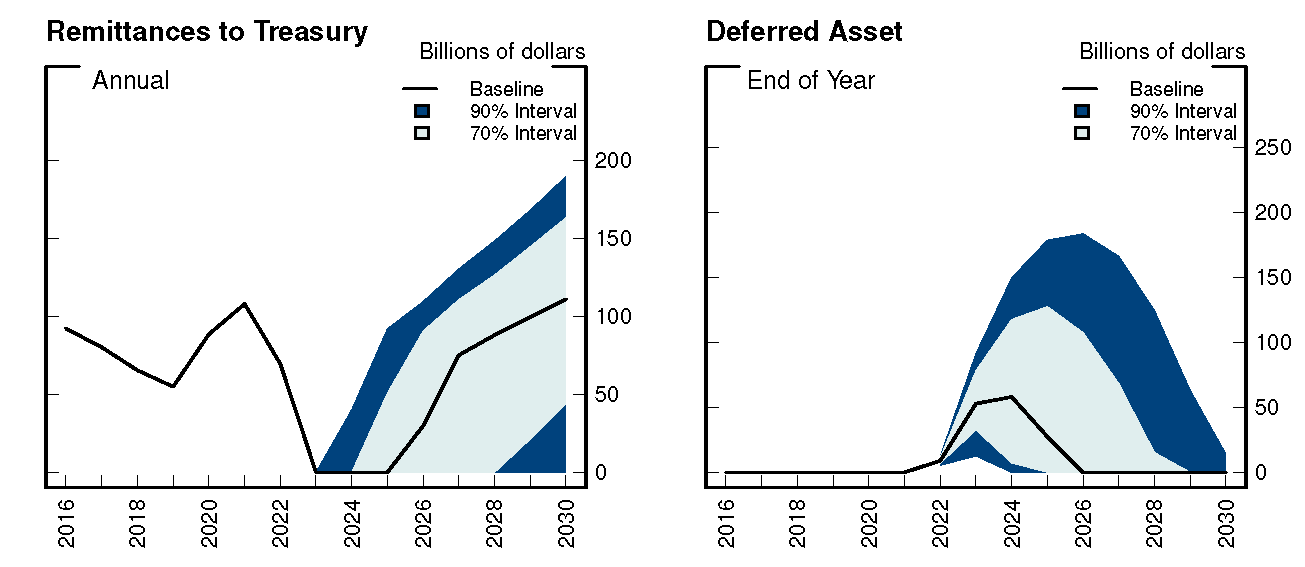

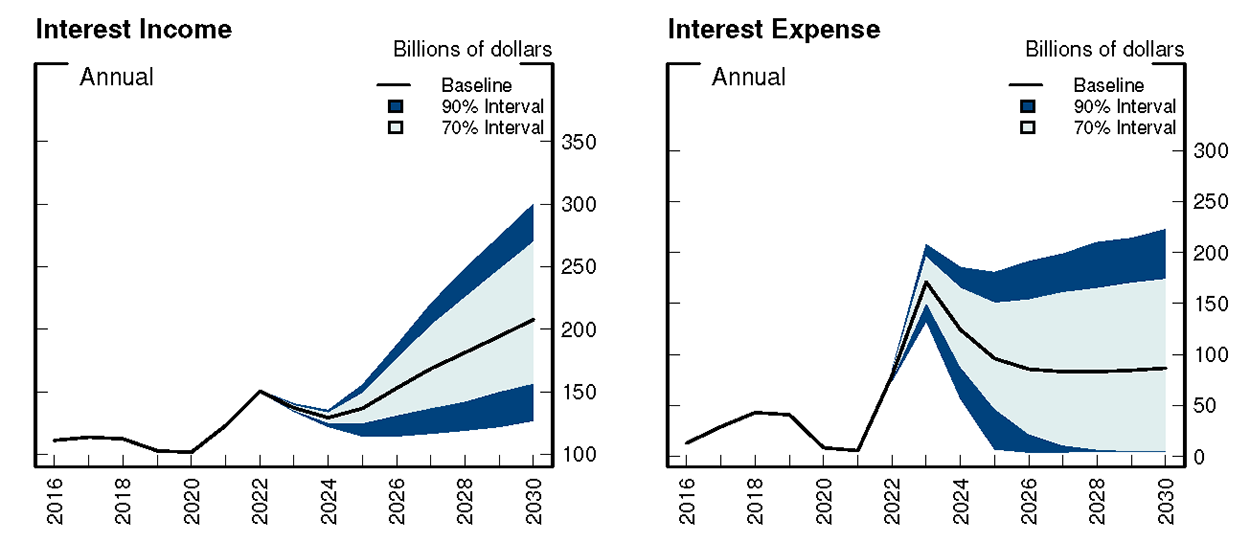

But when short-term rates the Fed pays rise sufficiently above the Fed's interest earnings, the Fed loses money. It stops sending interest earnings to the Treasury. The graph is in essence the amount the Fed owes the Treasury in this scheme. Usually the Fed makes some money -- the graph goes up -- then the Fed pays out to the Treasury and the graph goes back to near zero. When the Fed loses money, the Treasury doesn't send a check. Instead, the Fed accumulates its losses, $16 billion so far. The Fed then will wait to make this amount back again before it starts sending money back to the Treasury.

For broad brush macroeconomics, the Fed and Treasury are left and right pockets of the federal government. As interest rates rise, the government is going to pay more interest on its debt.

The Fed's massive QE operation has undone a lot of the Treasury's long-term debt, which would have kept interest costs from rising so fast. So, really, this is just a measure of the extra interest on the debt that QE has caused. The Fed and Treasury like to think of themselves as more separate, so there are political and institutional implications.

$16 billion isn't a huge amount in today's Washington, but the graph is interesting on a process starting to get under way.

No, the Fed is not about to go bankrupt. The Fed can print money, so conventional bankruptcy that happens when you can't pay bills simply cannot happen. If the Fed had no assets at all, it could simply print money -- create new reserves -- to pay the interest on outstanding reserves. That would only come to an end if the Fed had to soak up reserves or cash by selling assets to avoid inflation.

The accounting is a little weird. The Fed only counts interest income, and ignores mark to market values. So this is the accumulated amount of interest received on the Fed's assets minus interest paid on reserves. The Fed has, of course, taken a bath in mark to market values as interest rates rise. The Fed doesn't worry about it, because it can hold the securities to maturity. However, this means the Fed will likely have to hold them to maturity. The Fed now has $8.5 trillion of assets. A speedy "quantitative tightening," selling those assets, would force it to recognize mark to market losses. So don't count on that event. Fortunately, in my view of the world, QE didn't do much but shorten the maturity structure of outstanding debt, so the lack of QT won't be missed. Others disagree.

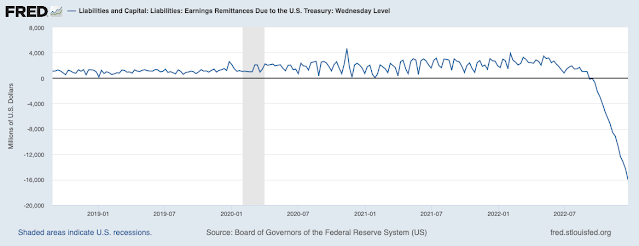

Alyssa Anderson, Philippa Marks, Dave Na, Bernd Schlusche, and Zeynep Senyuz at the Fed have a very nice analysis of this situation, along with explanations of how it all works. They use the following projections of interest rates

With those projections, here's what happens to the Fed's interest income and expense:

Notice how interest income dips 2022-2025 even though interest rates are rising. The Fed is still sitting on old bonds with very low interest rates. Interest income starts rising when these mature, and the Fed reinvests in new bonds with higher interest rates. Interest expense largely follows the reasonably rosy scenario that the funds rate eases as inflation goes away. (Top left graph looks like botton right graph.) |

Remittance to the treasury stop for a few years, while interest expense is greater than earnings. But then pick up again once the Fed can roll over its asset portfolio. The "deferred asset," which is the inverse of my top graph rises, rises considerably above today's $16 billion, but then goes away once the Fed rolls over its assets and interest earnings recover.

"A perpetually negatively sloped yield curve is also possible."

ReplyDeleteCould you explain that a bit more? Conventional wisdom would view inverted curves as something of an unstable state. Theoretically it could stay inverted for a long period of time, just as a radioactive isotope could not decay for a long period of time, but the (ex ante) likelihood approaches zero as the length of that period increases. I take it, though, you meant something stronger when you said it was possible

Actually, when you teach fixed income, you discover how natural an inverted yield curve is, and how hard it is to patch up models to deliver a rising yield curve. Without inflation, long-term bonds are the safe asset for long term investors, and short term bonds are risky, since they have reinvestment risk when interest rates change. Ergo, the risk premium is on short term bonds not long term bonds. I gather the 19th century saw this, though I'm not an expert. The Downton Abbey class bought perpetuities as their main risk free asset, not overnight repo, and the gold standard meant no long term inflation. Inflation can change that, make nominal short term bonds safer than long term bonds, though the indexed term structure should be negatively sloping.

DeleteThank you, that gives me enough of a starting point to do some further digging on this.

DeleteReinvestment risk should also come with reinvestment reward- there is no expectation of only lower interest rates at the maturity of short term bonds and you can just as well hope/expect higher long term returns by rolling short bonds as you can expect lower long term returns by rolling short bonds. Long bonds in the other direction run currency risk (or inflation risk), but that actually is asymmetric as currency regimes are not set up to increase the value of currency over time, but to decrease it. Even ignoring outright default risk, the long bond should pay more than a short bond under unbacked currency regimes and only in backed (gold standard) regimes should the curve be flat/inverted.

Delete"Actually, when you teach fixed income, you discover how natural an inverted yield curve is, and how hard it is to patch up models to deliver a rising yield curve."

DeleteSure, if the only thing you teach in a fixed income class is government bonds under stable political regimes.

It's not that difficult to get to a positively sloped yield curve in the corporate bond market when you add default risk as part of the term premium.

The most interesting interaction that you did not mention is how the deferred asset could interact with rising rates. The deferred asset is QE in disguise. It involves the Fed printing money in order to pay the IOR and RRP facility rates. If rates continue to rise, then the Fed would be raising rates and printing a lot of money at the same time.

ReplyDeleteThere needs to be a more meaningful division of responsibility between the Fed and Treasury. The Fed arguably has too much power now that it can adjust both interest rates and the government's duration position.

ReplyDeleteIf the Fed held only short term or floating rate paper this wouldn't be an issue.

Yes. And if the Treasury issued floating rate overnight debt, that would all be a lot easier and more transparent. Then the Fed could go back to serving banks. Money funds, now repoing trillions at the Fed, could just buy overnight treasurys.

DeleteAgreed, the size of the money market complex in the US entails a structural demand for short term Treasury debt. That demand is currently being met though the RRP facility. Even with the RRP facility, bills still often trade 0.5% or more lower than term repo rates (as implied by SOFR swaps).

DeleteAs it stands now it would be beneficial for the Treasury to issue more short term paper and use interest rate swaps to extend the duration of their liabilities.

This is all a bit tangential to how much power the Fed now has over the government's fiscal position but still important.

The Fed could also stop paying interest on reserves. They only started doing that recently (IIRC it was during the Panic of 2008).

ReplyDeleteAnd if they do, banks will respond pretty much the same as your bank will respond if you stop paying your mortgage. Banks only hold trillions of reserves because they get interest. Even the Fed must respect the demand curve for its products.

DeleteI covered all of this ground in a Barron's piece a while back, including (a) the effective shortening of the maturity of government debt, (b) the subterfuge of "deferred assets" to cover losses, and (c) the importance of duration in calculating the unrealized (and never-likely-to-be-realized) mark-to-market losses. The issue is slightly more complicated and even more interesting in Europe.

DeleteLeslie: How about a link?

DeleteJohn: Ok. Work with me. The Fed shrinks its bloated balance sheet. Why is that a problem, for us poor taxpayers.

"Banks only hold trillions of reserves because they get interest." It's a little more complicated than that. Banks hold two forms of reserves in varying proportions: 1) vault reserves, and, 2) reserves held in the Federal Reserve Banks. Vault reserves are typically Federal Reserve notes ('dollar bills'), and coins. Commercial banks would experience great inconvenience and expense if they chose to hold the majority of their reserves in the form of vault reserves, i.e., cash. Settlement of changes in the commercial bank's liabilities to other other commercial banks would be greatly complicated and result in the daily delivery of cash (Federal Reserve notes) from commercial bank to commercial bank, compared to the ease of transaction settlements through electronic exchange of reserve positions held at the Federal Reserve Banks.

DeleteThe only effect of the deficit arising from higher FFR is the impact of the loss to the Treasury of remittance income from the Federal Reserve Banks. The Treasury will, ceteris paribus, be required to float larger bill and note borrowings to cover what would otherwise be covered by FRB remittances.

As the various authors of the FED Notes publications note, no pun intended, the Federal Reserve Banks do not follow Generally Accepted Accounting Principles ("GAAP"). "Mark to market" rules required of the commercial banks' trading departments and lending branches do not apply to the Federal Reserve Banks. There will never be a run on a Federal Reserve Bank, as you implicitly acknowledge above.

Bottom-line, this is a 'tempest in a teapot', as the quaint English expression goes.

Bye the bye, periods of inflation and deflation were characteristic of the eras of free convertiblity of notes for bullion and species. Inflation is not the sole preserve of non-convertible or 'fiat' currencies. The expression "the corn price of gold" is a reflection of the potential for inflation occurring when coinage was based on a metallic standard of convertibilty. Adam Smith noted this phenomenon in his "Wealth of Nations" while observing the inflation in prices in Spain during periods of large imports of bullion from mines in the Spanish held colonies in the Americas.

Yes. And, it could do this while also requiring the reserves. For a long time, changing the amount of required reserves was a tool of monetary policy.

DeleteInstead of the federal government borrowing money to stimulate the economy, wouldn't money financed fiscal programs, perhaps in smaller doses, be a better option?

ReplyDeleteNo it would not. This:

Deletehttps://musingsandrumblings.blogspot.com/2019/09/the-case-for-equity-sold-by-u.html

From a controls theory perspective you will want two tools to achieve two separate objectives - for instance if you want to pound nails and turn screws, you will want a hammer and a screw driver.

DeleteSame thing in economics. If you want to achieve multiple economic objectives (for instance low inflation, high real growth), you will want more than one tool as well.

The missing fiscal tool:

https://musingsandrumblings.blogspot.com/2019/09/the-case-for-equity-sold-by-u.html

The Keynesian economists at the FED don't know the difference between money and liquid assets, between credit creators and credit transmitters. Powell thinks banks are intermediaries. That's why Powell eliminated required reserves and deposit classifications.

ReplyDeleteAs Friedman pontificated: From Carol A. Ledenham’s Hoover Institution archives:

“I would make reserve requirements the same for time and demand deposits”. Dec. 16, 1959.

"the grumpy economist can think of plenty of ways this can go wrong" AND no one or institution can predict what catastrophe could occur before 2030, invalidating these Fed estimates on deferred assets. Bottom line is that the Fed needs to encourage more fiscal coordination with its monetary policies, but I am preaching to the choir here and given the recent $1.7T omnibus spending bill, unlikely to happen...

ReplyDeleteThe Fed should buy gold with its funny money. Other smart central banks are doing just that. China has more gold than any country but does not disclose its true reserves. Who knows - maybe 10,000 tons/15,000 tons? The US has 8,000 tons. The window while the US dollar is high is the time to do this - like now, but our PhD economists at the FED are nothing if not bien pensant and utterly closed minded.

ReplyDelete"But when short-term rates the Fed pays rise sufficiently above the Fed's interest earnings, the Fed loses money. It stops sending interest earnings to the Treasury. The graph is in essence the amount the Fed owes the Treasury in this scheme."

ReplyDeleteNo, the Fed is not losing money in any way, shape, or form.

The graph is basically showing that the Fed is retaining more interest on the bonds that it holds (paying it as interest on reserves?) than it is paying back to Treasury.

Remember the interest payments that it receives can go to either recipient.