With amazing speed and impeccable timing, Erica Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru analyze how exposed the rest of the banking system is to an interest rate rise.

Recap: SVB failed, basically, because it funded a portfolio of long-term bonds and loans with run-prone uninsured deposits. Interest rates rose, the market value of the assets fell below the value of the deposits. When people wanted their money back, the bank would have to sell at low prices, and there would not be enough for everyone. Depositors ran to be the first to get their money out. In my previous post, I expressed astonishment that the immense bank regulatory apparatus did not notice this huge and elementary risk. It takes putting 2+2 together: lots of uninsured deposits, big interest rate risk exposure. But 2+2=4 is not advanced math.

How widespread is this issue? And how widespread is the regulatory failure? One would think, as you put on the parachute before jumping out of a plane, that the Fed would have checked that raising interest rates to combat inflation would not tank lots of banks.

Banks are allowed to report the "hold to maturity" "book value" or face value of long term assets. If a bank bought a bond for $100 (book value) or if a bond promises $100 in 10 years (hold to maturity value), basically, the bank may say it's worth $100, even though the bank might only be able to sell the bond for $75 if they need to stop a run. So one way to put the issue is, how much lower are mark to market values than book values?

The paper (abstract):

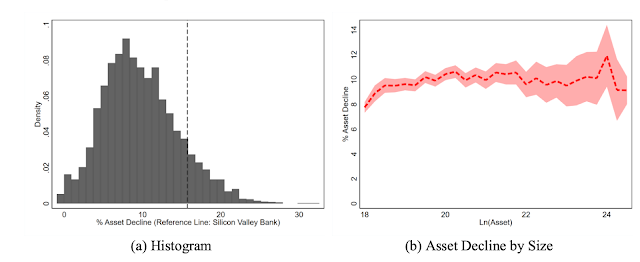

The U.S. banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity. Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%.

... 10 percent of banks have larger unrecognized losses than those at SVB. Nor was SVB the worst capitalized bank, with 10 percent of banks have lower capitalization than SVB. On the other hand, SVB had a disproportional share of uninsured funding: only 1 percent of banks had higher uninsured leverage.

... Even if only half of uninsured depositors decide to withdraw, almost 190 banks are at a potential risk of impairment to insured depositors, with potentially $300 billion of insured deposits at risk. ... these calculations suggests that recent declines in bank asset values very significantly increased the fragility of the US banking system to uninsured depositor runs.

Data:

we use bank call report data capturing asset and liability composition of all US banks (over 4800 institutions) combined with market-level prices of long-duration assets.

How big and widespread are unrecognized losses?

The average banks’ unrealized losses are around 10% after marking to market. The 5% of banks with worst unrealized losses experience asset declines of about 20%. We note that these losses amount to a stunning 96% of the pre-tightening aggregate bank capitalization.

|

| Percentage of asset value decline when assets are mark-to- market according to market price growth from 2022Q1 to 2023Q1 |

The median bank funds 9% of their assets with equity, 65% with insured deposits, and 26% with uninsured debt comprising uninsured deposits and other debt funding....SVB did stand out from other banks in its distribution of uninsured leverage, the ratio of uninsured debt to assets...SVB was in the 1st percentile of distribution in insured leverage. Over 78 percent of its assets was funded by uninsured deposits.

But it is not totally alone

the 95th percentile [most dangerous] bank uses 52 percent of uninsured debt. For this bank, even if only half of uninsured depositors panic, this leads to a withdrawal of one quarter of total marked to market value of the bank.

|

| Uninsured deposit to asset ratios calculated based on 2022Q1 balance sheets and mark-to-market values |

Overall, though,

...we consider whether the assets in the U.S. banking system are large enough to cover all uninsured deposits. Intuitively, this situation would arise if all uninsured deposits were to run, and the FDIC did not close the bank prior to the run ending. ...virtually all banks (barring two) have enough assets to cover their uninsured deposit obligations. ... there is little reason for uninsured depositors to run.

... SVB, is [was] one of the worst banks in this regard. Its marked-to-market assets are [were] barely enough to cover its uninsured deposits.

Breathe a temporary sigh of relief.

I am struck in the tables by the absence of wholesale funding. Banks used to get a lot of their money from repurchase agreements, commercial paper, and other uninsured and run-prone sources of funding. If that's over, so much the better. But I may be misunderstanding the tables.

Summary: Banks were borrowing short and lending long, and not hedging their interest rate risk. As interest rates rise, bank asset values will fall. That has all sorts of ramifications. But for the moment, there is not a danger of a massive run. And the blanket guarantee on all deposits rules that out anyway.

Their bottom line:

There are several medium-run regulatory responses one can consider to an uninsured deposit crisis. One is to expand even more complex banking regulation on how banks account for mark to market losses. However, such rules and regulation, implemented by myriad of regulators with overlapping jurisdictions might not address the core issue at hand consistently

I love understated prose.

There does need to be retrospective. How are 100,000 pages of rules not enough to spot plain-vanilla duration risk -- no complex derivatives here -- combined with uninsured deposits? If four authors can do this in a weekend, how does the whole Fed and state regulators miss this in a year? (Ok, four really smart and hardworking authors, but still... )

Alternatively, banks could face stricter capital requirement... Discussions of this nature remind us of the heated debate that occurredafter the 2007 financial crisis, which many might argue did not result in sufficient progress on bank capital requirements...

My bottom line (again)

This debacle goes to prove that the whole architecture is hopeless: guarantee depositors and other creditors, regulators will make sure that banks don't take too many risks. If they can't see this, patching the ship again will not work.

If banks channeled all deposits into interest-paying reserves or short-term treasury debt, and financed all long-term lending with long-term liabilities, maturity-matched long-term debt and lots of equity, we would end private sector financial crises forever. Are the benefits of the current system worth it? (Plug for "towards a run-free financial system." "Private sector" because a sovereign debt crisis is something else entirely.)

(A few other issues stand out in the SVB debacle. Apparently SVB did try to issue equity, but the run broke out before they could do so. Apparently, the Fed tried to find a buyer, but the anti-merger sentiments of the administration plus bad memories of how buyers were treated after 2008 stopped that. Beating up on mergers and buyers of bad banks has come back to haunt our regulators.)

Update:

(Thanks to Jonathan Parker) It looks like the methodology does not mark to market derivatives positions. (It would be hard to see how it could do so!) Thus a bank that protects itself with swap contracts would look worse than it actually is. (Translation: Banks can enter a contract that costs nothing, in which they pay a fixed rate of interest and receive a floating rate of interest. When interest rates go up, this contract makes a lot of money! )

Amit confirms,

As we say in our note, due to data limitations, we do not account for interest rate hedges across the banks. As far as we know SVB was not using such hedges...

Of course if they are, one has to ask who is the counterparty to such hedges and be sure they won't similarly blow up. AIG comes to mind.

He adds:

note we don’t account for changes in credit risk on the asset side. All things equal this can make things worse for borrowers and their creditors with increases in interest rates. Think for a moment about real estate borrowers and pressures in sectors such as commercial real estate/offices etc. One could argue this number would be large.

So don't sleep too well.

From an email correspondent:

Besides regulation, accountancy itself is a joke. KPMG Gave SVB, Signature Bank Clean Bill of Health Weeks Before Collapse.

How can unrealised losses near equal to a bank's capital be ignored in the true and fair assessment of its financial condition (the core statement of an audit leaving out all the disclaimers) just because it was classified as Held to Maturity owing some nebulous past "intention" (whatever that was ever worth) not to sell?

It strikes me that both accounting and regulation have become so complicated that they blind intelligent people to obvious elephants in the room.

Typos: SBV should be SVB.

ReplyDeleteWhere does First Republic stand in all this? (Wishing I was asking for a friend)

ReplyDeleteyou ;can see it all in their 10Q's and 10K's At Sept 30, SVB's unrealized loss on investment securities exceeded their net worth. And that was almost six months ago, but nobody apparently paid attention.

DeleteFor FRC it's nowhere near as bad.

The information is available in their 10K's and 10Q's. For SVB, as far back as 9/30/22 the unrealized loss on their held-to-maturity securities exceeded their net worth. So it was plain six months ago they were in trouble. But apparently people didn't pay attention.

DeleteFor FRC, they have a loss but not as bad as for SVB.

It's nuts that there is no public disclosure on the SVB auction. News reports say there was at least one bid, but that it was rejected by the regulators. So it's possible we could have all been out of this with all depositors whole without any new government guarantee on all deposits, but who knows what's happening because they apparently get to make the process up as they go and conduct the auction in private. So corrupt!

ReplyDeleteThis is likely what the FDIC refers to as an assisted sale. The bid price is how much money the FDIC gives the buyer, in addition to all the remaining assets and liabilities.

Delete"For runs to be a social problem, Diamond and Dybvig (1983) assume that real projects are abandoned after a run."

ReplyDelete--- J. H. Cochrane, "Toward a run-free financial system", (Nov. 4 2014) in Martin Neil Baily, John B. Taylor, eds., Across the Great Divide: New Perspectives on the Financial Crisis, p. 204. Hoover Press.

This is an appropriate criterion for determining whether the FRB, UST, and the FDIC should become involved in supporting state- and federally-chartered bank holding company depositors whose deposits in the failing bank are uninsured.

Does SIVB meet the threshold set by this criterion?

Ironically, one of the worst offenders is the Fed itself which has 2.61 T$ of mortgage backed securities on its balance sheet as of last week. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/

ReplyDeleteMortgage backed are worse than long bonds because increasing rates stretches out their duration.

Release H.4.1 does not disclose what percentage of the Fed's 4.57 T$ of notes and bills are long term.

The Fed, as a bank, is by its own standards woefully undercapitalized. It is carrying total assets of 8.342 T$ on a mere 42.5 G$ of capital. 0.5%.

If the Fed were a bank regulated by the Fed, it would put itself in receivership.

What he said!

DeleteYou mention that they attempted to sell capital but the FDIC stepped in. I believe what happened was they tried to sell capital. That's not highly unusual. Then Roth billionaire Peter Thiel got wind of it and called his buddies to get their cash out and caused the actual bank run. SVB isn't without fault. 37,000 depositors averaging 4.2M aren't without fault. But I'd like to know if causing a bank run is something that should be investigated (and downright discouraged)? It's wreckless. Particularly in this age of online transfers. It's not like to old days of lining up at the door. No bank is safe if 1/3rd of their deposits are outgoing in one business day. "Blue horseshoe loves Anacott Steel," Any jackwagon can screw with the system apparently scot free.

ReplyDeleteMaybe the risk officer should have been doing her job

DeleteThey did not have a risk officer !

DeleteI am not sure given the shape of the curve that the Fed engineered since 2008 that any bank could have carried long bonds and maintained an effective hedging strategy, which would not just be equivalent or better implemented by carrying short term debt. However, even if banks hedged the duration risk, it does seem that given size of the treasury float diversification across asset classes and firms is not enough to diffuse it so somewhere they would have needed counterparties to take on the risk.

ReplyDeleteThe government issued debt at rock bottom rates at very long durations for a long time, the Fed repeatedly said ZIRP is here to stay, giving the impression there would be time to unload risk if needed. Ultimately the government and Fed did not back up implicit and explicit commitments with credible fiscal policy, in fact stepping on the fiscal gas pedal at the same time it implemented extremely rapid monetary policy to hit the brakes. That duration risk had to be borne and absorbed somewhere, and there are simply not enough retail investors to do it. So institutions have to, and perversely it seems that the more effective most participants do so, the more extreme the cracks will be at those who did not. So the bad tail end of the banks will look much worse than most, as the post discusses. Cracks have to appear somewhere.

I am just not sure there are not also a 'few' insurance cos or some hedge funds which will soon 'surprise' the markets.

Imagine what the path could have looked like if congress had issued a responsible fiscal path forward including reducing spending in constrained areas, and emphasizing future restraint and growth. Instead we spent all our time celebrating that an additional 6 trillion was not spent, ignoring fact the Federal budget is 55% larger than pre-covid and none of the long term problems have been addressed.

I would love for Powell to just bluntly tell the senators at his next meeting asking what could have been done: "would be nice to get some fiscal help from you, rather than more regulatory edicts"

Can you comment on Japan's situation (263% GDP at greater than 9yr maturity) vs US. The BOJ was remarkably reluctant to raise rates in the face of recent inflation -- is this due to not wishing to restart the deflationary spiral or were they aware of the fact they would cripple their bond holders (or given amount held as I understand by populace directly, they don't see systemic issues)? Or were they just lucky their inflation was mehh by rest of world standard and so they were able to thread the needle mostly by inaction.

ReplyDeletetodays corrupt central banks believe by forcing inflation they can wash away the sins of their past. Problem is...they BORROW ever more to do this...making the SINS ever greater!

DeleteSVB never should have had FDIC insurance at all. It was a self-dealing snake, too cocksure and frivolous to notice it was eating its own tail.

ReplyDeleteI largely agree with John Cochrane in this excellent post.

ReplyDeleteMoreover, if we mark to market the value of real estate assets, and there is a decline in real estate values, then every bank in America is in peril.

Another solution is hardly any regulations, except that every bank with federally insured deposits must keep a very fat layer of convertible bonds in place, perhaps at 25% of liabilities outstanding.

I agree with the convertible bond idea. I assume you mean subordinated bonds.

DeleteIs there any sensitivity study between further rate hikes and increases in unrealized losses? How much does it take to get more regional banks into negative net worth territory for example, 100 bps? Also, what about regular mortgages, shouldn’t those be treated similarly to bonds in a mark to market scenario? Why are we only talking about bonds, mortgages are a lot worse from a liquidity perspective, they are de facto illiquid, but have the same rate sensitivity, I would think.

ReplyDeleteJohn thanks for being sensical...in a nonsensical world. Until we start PUNISHING the people creating these problems they will continue. I think all bailout of banks should come from financial firms....not taxpayers. They want self regulation...well then hedgefunds, banks, brokers, private equity...should be MADE to FUND these mistake. Or better yet...let them FAIL... I propose a 5% tax on all wall street transactions to make it about investing, not HFT. I pay sales tax for a car....so SHOULD THEY for their shiny toys!

ReplyDeleteJohn: This reflects problems on so many levels it's hard to know where to start.

ReplyDeleteFirst, accounting firms: None of them is going to publicly proclaim that the financial heart of Silicon Valley is up a creek! It doesn't matter what their analysis says. SVB has too many friends in high places.

Second, regarding missing the basics: Unfortunately this is a nationwide problem. Our educated "elite" often don't seem to actually know the basics. They're very interested in finding every kind of biased analysis to help them to their political objectives, and **very very very very** uninterested in the drudgery of how things actually work. In my debates with educated people (of which I am one), I find they're frequently flummoxed by the fact that their claims are wildly at odds with basic observable facts. They're more interested in making claims than in verifying them. The dim-witted political elite is hardly helping this phenomenon. My senator has a P.E. degree from Cow-town university. She's more than happy to flog any "expert" view that advances her political agenda, astoundingly at odds with reality though it may be.

Third, declining education: Our schools and universities suck. They've 86d education to become a rubber-stamping social-justice-warring credential-floggers. They really don't give shit if you don't know anything when you graduate. Butts in chairs generate cash flow.

Fourth: total lack of responsibility. No one takes responsibility for anything. The buck never stops. Why stick your neck out (Fed or accounting firms) on SVB when you can find even the flimsiest excuse to pass the buck? This, by the way, is the reason regulation ultimately winds up useless. No one wants to risk their career by putting a red flag on a high profile bank/tech firm/etc. Some short sellers did identify this problem and bet against SVB, but apparently no one with deposits was paying much attention.

Fifth: back to basics basics: I saw an interview with a start-up CEO, who was able to pull her company's money out in time thanks to an early alert from an investor. She complained that she has no idea what banks do, she's a health care technical person!!! Well where was her CFO???? Isn't that the CFO's most fundamental job? The point is that the "basics" problem goes back to education and permeates our entire culture.

I could go on but I guess I'll stop there.

John: One thing I like about both your blog and your economics is that you consistently present and consider both sides of an argument. That's not so common these days, so thanks for doing that, much appreciated!

DeleteHave you ever been in a 10 person company? A start-up? A 100 person company? There is no CFO... the CEO does it all, 18 hours a day, 7 days a week. A system with instant transfer of all deposits via a cell phone that is dependent on every entrepreneur and every homeowner to police the banks, when even the genius analysts on wall street couldn't figure it out, doesn't work in any world I've ever seen.

DeleteThis is great - thanks

ReplyDeleteSince KPMG gave two thumbs up to these two banks, will shareholders have any recourse against them?

ReplyDeleteNothing is any more elemental in financial risk management than duration mismatch risk. It is ridiculous that bank regulators and accounting standards willing fully ignor it. The held-for-maturity concept is totally worthless when the liabilities are short-term. In the 1990's I managed some the largest derivative hedge programs in the insurance industry, with derivatives (swaps, futures, options, currency forwards) used only for the purpose of reducing macro tail risks. It was frustrating that regulation/accounting could make a company that was prudently managing its risk look much riskier than similar company that ignored its mismatches. Financial disasters are caused by the actual economics of the assets vs. liabilities. Ignoring these realities ultimately will result in crises, and things will look fine until a huge hole "suddenly" appears below the feet. Regulators/accountants encouraging ignoring the actual mark to market of assets and liabilities is a HUGE moral hazard that cause problems to be "too big to save". I would place most of the blame on the 2009's elimination of mark to market requirements (which is the biggest cause of the stock market's truncated bear market) and 15 years (maybe more going back to 2000) of artificially too low interest rates.

ReplyDeleteYou can't. As long as the depositors are being told that they can have their currency "on demand" even thought their funds are never kept but used in lending (tho banks don't need deposits to originate loans).

DeleteYou can't insure or make something solvent when by design the banking system is insolvent.

Depositors are misled thinking they are depositors and not lenders to the bank.

It's all a confidence trick that even John fails on purpose or not to acknowledge.

Until we don't decouple banks from taking deposits and then putting the funds on their balance sheet using them forward maybe in lending to a non risky segregated accounts banking, we will always have problems with banks doing stupid things to maximize profits at the expense of their lenders (depositors).

Like, JPM is paying 0.25 for the checking accounts while they take the funds and lend them short or long at 4-7%. Like what the hell is that?. How many brain cells as an economist you have to miss to not see the obvious?.

The banking problems are by design and structural. Banks are all insolvent by design and will all be illiquid if the taxpayer FDIC backed insurance wouldn't exist.

You can't. As long as the depositors are being told that they can have their currency "on demand" even thought their funds are never kept but used in lending (tho banks don't need deposits to originate loans).

DeleteYou can't insure or make something solvent when by design the banking system is insolvent.

Depositors are misled thinking they are depositors and not lenders to the bank.

It's all a confidence trick that even John fails on purpose or not to acknowledge.

Until we don't decouple banks from taking deposits and then putting the funds on their balance sheet using them forward maybe in lending to a non risky segregated accounts banking, we will always have problems with banks doing stupid things to maximize profits at the expense of their lenders (depositors).

Like, JPM is paying 0.25 for the checking accounts while they take the funds and lend them short or long at 4-7%. Like what the hell is that?. How many brain cells as an economist you have to miss to not see the obvious?.

The banking problems are by design and structural. Banks are all insolvent by design and will all be illiquid if the taxpayer FDIC backed insurance wouldn't exist.

The very function of commercial banking, which is to offer fully liquid deposit services and then convert the deposits to longer term funding to individuals, businesses, and institutions, is fundamentally unstable. It only works when everyone has the confidence to stay in the game. Banks (should) minimize the risk by making sure capital reserves are enough to cover fluctuations in assets (and liability) values across the interest rate horizon. The standard ALCO model the even smallest banks review on a quarterly basis calculates the impact on capital of 100, 200, and 400 bps rate shocks in both directions (as if everything on the balance sheet was marked to market), and boards are responsible for ensuring that the resulting analysis falls within written risk tolerances (usually in the 20-30% of regulatory capital level). I am confident the SVB models were screaming for all of 2022 that the bank was out of tolerance. Not raising capital 9 months ago was gross negligence. Regulators not demanding they do so is unfathomable. The price of their failure - risk of contagion - is fundamentally different in this age of same-day ACH and instant communication. Our policies and even beliefs about the banking system (as distinct from banks) must change.

ReplyDeleteSVB -- hedging not required/allowed because the treasury bond positions not marked to market.

ReplyDeleteI'm a retired international banker with a specialty in risk assessment. It occurred to me this morning that the risk of an uninsured deposit could be quite seriously mitigated by automatically collateralizing such deposits by the liquid assets that are maintained in the form of treasuries and/or mortgage backed securities (and the like) at their face value. The risk to the depositor would be reduced to fluctuations in the market value of the securities. The depositor could diminish such minimal risk by purchasing hedges on the securities. The interest paid on these deposits would be less than that paid on unguaranteed deposits, thereby reducing the bank's funding costs. The risk of bank bailouts to tax payers would be none. Unfettered moral hazard would remain.

ReplyDelete